By Nicole Saldarriaga

Sometime in the fourth century B.C.E, an Athenian woman by the name of Agnodice was brought before a jury full of incredibly angry men—and she responded by calmly taking off her clothes.

Agnodice disrobing

Agnodice disrobingBefore I make it seem as if this is an article about ancient prostitution (or plain mental instability) let me clarify: Agnodice had been dressed as a man, and was brought before the jury under charges of having seduced the women of Athens—in taking off her clothing she not only proved her true gender and the charges false, but also made medical and gynecological history.

Before we can really dive into Agnodice’s story however, it’s important to point out that it is one of those tales which has always been, and will probably always be, a historical mystery. Some scholars adamantly believe that it is historical fact, while others place it in the realm of myth and legend. We may never know the real answer—but it is, without a doubt, a good story.

According to legend, Agnodice, also called Agnodike, was born into a wealthy Athenian family around the fourth century B.C.E. As she grew up, Agnodice was appalled by the high mortality rate of infants and mothers during childbirth, a traumatizing factor of female life that inspired Agnodice to study medicine—or at least to desire it. She had unfortunately been born into a time during which women were prohibited from studying or practicing any form of medicine, especially gynecology—in fact, it was considered a crime punishable by death.

Ironically, not long before Agnodice was born, women had had something of a monopoly on female medical treatment. Before the advent of Hippocratic medicine, childbirth was overseen by close female relatives or friends of the expectant mother, all of whom would have undergone labor themselves, and could therefore draw from their own experience as they coached other women through the process. Women who had a particular knack for this position slowly came to be known as maia, or midwives.

Stone relief of a midwife assisting with childbirth, Isola Della’ Sacra, Ostia, 1st century CE

Stone relief of a midwife assisting with childbirth, Isola Della’ Sacra, Ostia, 1st century CEThis practice was widely accepted for several years, and over time it truly began to flourish. Midwives began to accumulate an impressive breadth of lore and talent, learning enough to perform abortions, teach women about contraception and supposedly (though this is more unlikely) help women practice gender determination when attempting to become pregnant.

As men began to realize the capabilities of midwives, however, they began to feel extremely uncomfortable—even intimidated. In a world in which anxiety over lineage and heirs dominated much of the culture, the sheer amount of sexual independence offered to women by midwives and their reproductive knowledge posed a seemingly enormous threat. Men no longer wanted midwives to practice their medicine. Instead, they themselves attempted to dominate the medical field—a goal that, by the end of the fifth century B.C.E, was made more attainable with the help of Hippocrates (known today as the “Father of Medicine”) and his teaching facilities, which only admitted men. It is at this point that midwifery became punishable by death.

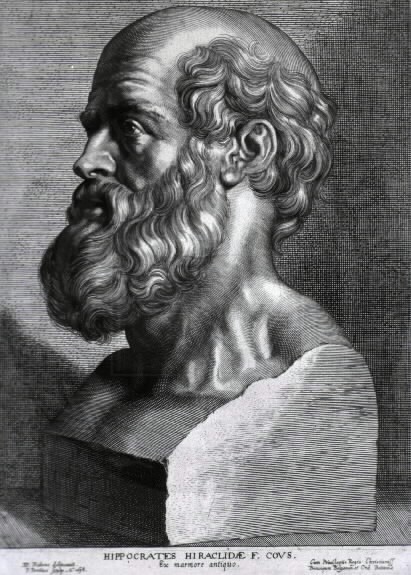

Hippocrates, known as the Father of Medicine

Hippocrates, known as the Father of MedicineThis proved to be a terrible blow to women—not just the women who suddenly had to give up their livelihoods, but also to the women whose labors and deliveries, without the guidance of a midwife, often ended in disaster. If you’re wondering why male doctors didn’t just take over and prevent these deadly deliveries, they certainly tried; but, in a society that highly valued female modesty, the transition from female midwives to male doctors did not prove easy. Despite the advances of medicine ushered in by Hippocrates, and despite the willingness of newly trained men to take over the gynecological profession, women adamantly refused to let male physicians perform examinations or help with deliveries. This shyness earned women an extremely poor reputation with doctors, who began to see women as stubborn creatures with no interest in their own treatment or health. Many Hippocratic treatises that survive today describe this problem, though none admit that it could have been avoided if men had not outlawed midwifery. Worse still than this unnecessarily poor reputation was the skyrocketing number of deaths related to childbirth.

Enter Agnodice. Determined to do something about the deaths and excruciatingly difficult deliveries that so appalled her, but legally prohibited from helping, Agnodice cut off all her hair, dressed in male clothing, and traveled to Alexandria to study medicine under Herophilos of Chalcedon (335-280 B.C.E.).

Herophilos is considered the Father of Anatomy and was the first physician to use the pulse for medical purposes.

Herophilos is considered the Father of Anatomy and was the first physician to use the pulse for medical purposes.Under Herophilos, who was a follower of Hippocrates and a co-founder of the famous medical school at Alexandria, Agnodice—always in the guise of a man—learned a great deal of medicine. She then traveled back to her native Athens, where, legend has it, she heard the agonized screams of a woman in labor as she walked down the street. When she rushed in to help—still looking like a man—the mistrustful women in the room tried to force Agnodice out. Frustrated, Agnodice pulled aside her robes and revealed herself as a woman. The amazed and relieved expectant mother then accepted help from Agnodice, whose medical knowledge resulted in a safe delivery.

After this first success, news of Agnodice—who continued to dress as a man in order to practice medicine—spread throughout the female community. Suddenly, it seemed as if the services of a “male” doctor were constantly in demand. This was immediately suspicious to the men of Athens, who believed that Agnodice was somehow seducing their wives, sisters, and daughters. Some men even claimed that the women of Athens were faking illnesses in order to be seen by Agnodice. It is because of these accusations that she was first brought before a jury.

Agnodice

AgnodiceClearly, Agnodice could do nothing to disprove these charges other than to display the most obvious (and perhaps most scandalous) proof: and so, the legend goes, without hesitation she pulled open her robes and exposed herself to the jury.

This, of course, only made things worse for Agnodice. The revelation of her secret pushed the men of the jury from angry to livid. Furious that a woman had been practicing medicine openly, right under their noses, they immediately sentenced Agnodice to death and set a date for her execution.

Things were not looking good for this courageous cross-dresser—that is, until her patients realized what had happened.

A massive group of Athenian women (including a few very highborn wives of the men who wanted Agnodice dead) stormed the assembly, demanding that Agnodice be released. “You men are not spouses,” they said, “but enemies, since you are condemning her who discovered health for us.”

Faced with the wrath of their wives, the men relented and—amazingly—decided to change the law. Thanks to Agnodice, freeborn women could legally study and practice medicine, as long as they treated only female patients.

Agnodice’s story has earned her the title of “first female physician” or “first female gynecologist” in many circles, particularly in the medical world, and she herself has become a symbol of female equality, determination, and ingenuity. The big question here is, of course, did she really exist?

Hyginus’s Fabulae, illustrated with astronomical woodcuts

Hyginus’s Fabulae, illustrated with astronomical woodcutsThe only surviving record of Agnodice’s story is attributed to a Latin author named Gaius Julius Hyginus (64 B.C.E.—C.E. 17), most of whose many treatises have been lost. What now survives are two abbreviated texts—Fabulae and Poetical Astronomy—which are so poorly written that most scholars believe them to be a novice schoolboy’s notes on Hyginus’ treatises. The story of Agnodice’s cross-dressing and medical practice can be found in Fabulae, and comprises no more than a single paragraph in a section called “Inventors and their Inventions” (Section CCLXXIV).

While some scholars believe that this short record represents historical fact, or at least a legend built up around a real, historical personage, there are many factors that would seem to disprove this theory.

For example, Agnodice’s story contains key tropes which were often present in ancient legends and stories. Her bold decision to remove her garments in order to display her true gender, for instance, is a relatively frequent occurrence in ancient myths—so much so that archeologists have unearthed a number of terracotta figures which appear to be dramatically disrobing.

Agnodice’s name itself also makes her story seem less realistic. When literally translated, the name means “chaste before justice.” This practice of endowing a character with a name that points to some aspect of their story was very common in Greek myth and literature.

And, of course, there is the fact that her story appears at all in Hyginus’ Fabulae. After all, “fabulae” means “stories”—the text describes close to three hundred myths and divine blood lines, many of them extremely recognizable. It is essentially a collection of the Greek myths that any well-bred and cultured Roman student was expected to know. The very fact that Agnodice’s tale is included in such a text places her more in the realm of legend than of fact.

Myth or not, however, there is a lot to be learned from a story like Agnodice’s. In the end, Agnodice not only represents the (to this day slightly contentious) desire for women to control their own bodies, but also the underdog’s determination in the face of impossible odds or deadly threats. Her story also teaches us the importance of banding together as a community. Agnodice alone could never have changed the law in Athens—it was only with the help and support of her community that she was able to really effect any change. It is for these reasons that she remains an inspiration to women and men alike today.

One comment

This is an amazing article. I have heard of Agnodice before and I believe she is one of the most inspiring women in history. Whether she really existed is up to the individual’s belief and I think she really existed. Most likely she wasn’t named Agnodice at first but she got that name because of her role in allowing women to practice medicine and her story was probably different than the one we know but all legends are based on fact.

I think if Agnodice were to be reincarnated in this time she would be happy at how far we have come and she would continue to fight. Because “Girls Just Wanna Have Fundamental Human Rights”.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.