Sparta and… Scotland? Laconic wit through the centuries

Written by Stefan Sencerz, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Part 1 and part 2 of this series focus on angels in the Western tradition. Part 3 focuses on the Eastern tradition as does the following article, the final installment in the series.

There are, of course, some dissimilarities between devas and angels. For one thing, angels are not born and seem to be everlasting. Devas are born (or reborn) (Rg Veda i.143.2 and x.129.6) and do not remain in their heavens eternally. Although their life-spans are very long, eventually they exhaust their karma and are reborn in a different realm.

There are, however, some interesting similarities between them. Both devas and angels are purely spiritual (i.e., immaterial) beings. Devas seem to lack perfect knowledge or wisdom and generally do not interact with devas occupying plans of existence higher than their own.

They can also lack spiritual wisdom. For example, according to Kaushitaki Upanishad (Book 4), Indra was weaker than his adversaries, Asuras, before he come to know his own Atman (soul), suggesting a kind of spiritual awakening.

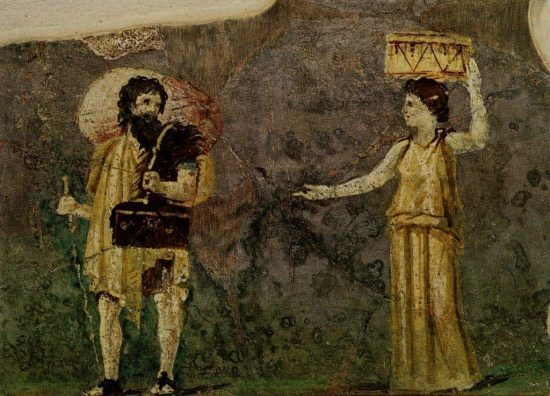

Indra and Sachi Riding the Divine Elephant Airavata, from a Panchakalyanaka (Five Auspicious Events in the Life of Jina Rishabhanatha ([Adinatha]), India

Perhaps most interestingly, both angels and devas display moral flaws. Some angels are excessively proud or jealous of humans. This leads to their rebellion against God and eventual fall. Similarly, many devas are too preoccupied with pleasures, failing to give proper respect to Buddha and his fully awakened disciples, who represent the perfect wisdom. Thus, they show a similar lack of humility.

Do angels and humans have more in common than we know? Could we, in fact, have been angels or devas in another life? The fact is, most of us do not remember our previous lives—should these exist. I surely do not. Maybe there is nothing to remember.

Maybe I have never been an angel and I have never fallen. Maybe I have always been just a bear, or a wolf, or a ghost, or a hungry spirit, or a human, or something. Maybe I am all of these at each and every moment. Maybe this is my one and only life. I don’t know. This is perhaps why I myself lean towards a metaphorical interpretation of the Six Realms.

When my mother took me on a tour of Auschwitz, where she had been imprisoned, it was obvious to me that she had endured and survived hell. What we do to animals, especially on factory farms, looks to me like condemning them to hell, too. When I observe politicians clinging to power, they apparently act like asuras. When I do something on the first instinct and only later think about it, I seem to be acting like an animal. And when I give in to my insatiate appetites, it seems like I am a hungry ghost (preta).

Thus, perhaps, I do simultaneously occupy all planes of existence implied by the Wheel of Life and Death. I am both a human and an animal, both a hungry ghost and a heavenly dweller, both a deva preoccupied by pleasure and an asura driven by anger and hate. The ultimate meaning of the myth may be that various dispositions and aspirations coexist in each and every one of us.

A great haiku master Kobayashi Issa (1763-1827), a devout Buddhist in Jōdo Shinshū or Amidist tradition, offers a poetic rendition of the myth of the Wheel of Life and Death.

Traditional bhavachakra wall mural of Yama holding the wheel of life, Buddha pointing the way out, photo by Ms Sarah Welch, Seattle, Washington

His six-part poem (translated here by Robert Haas) is entitled “The Six Ways”:

Hell

bright autumn moon –

pond snails crying

in the saucepan

The Hungry Ghosts

flowers scattering –

the water we thirst for

far off, in the mist

Animals

in the falling of petals–

they see no Buddha

no *Law

*“Law” is the translation of the Buddhist term “Dharma” which could be also translated as the “Truth”

Malignant Spirits (asuras)

in the shadow of blossoms,

voice against voice,

the gamblers

Men

we humans —

squirming around

among the blossoming flowers

The Heaven Dwellers

a hazy day —

even the gods

must feel listless

End of Part 4 of 4

Facebook is changing its algorithms. Change is often good, but these new alterations to how the news feed works means that if you get your news via Facebook, the social media giant might be preventing you from seeing Classical Wisdom content!

This isn’t great for you, and it’s not great for us; and it’s not great for history and the classics in general. If you take action, we can save what history has to offer.

How Do I Stop Facebook from Burying Classical Wisdom News?

Here’s how you can prevent the new algorithms from obscuring your daily Classical Wisdom news and updates.

‘Like’ and ‘Prioritize’ Classical Wisdom on Facebook. This may give the message that you want Classical Wisdom news in your feed, even if Facebook algorithms have other plans.

Make sure you have ‘liked’ and ‘followed’ Classical Wisdom Weekly in order to see our posts.

Subscribe – it’s easy and free – to our FREE weekly newsletter.

Sign up now and never miss your weekly dose of the classics. Ancient wisdom can come directly to your inbox for exciting lessons in history, art, philosophy, literature and more…

Sign up here for our Free Newsletter

Classical Wisdom, like all alternative media, is battling to exist in a larger mainstream media world. If we don’t do this now, and if we allow algorithms to dictate how we receive our knowledge, Classical Wisdom becomes history, and the larger companies will become your sole source of news. Even if you enjoy and depend upon the content of major news media, it’s best to get as MANY different sources as you can so you get alternative viewpoints and information that might be too ‘different’, ‘unpackaged’, or ‘real’ to be presented on the nightly TV news.

Go Straight to the Source

Don’t forget, you can always go the common-sense route and visit the website!

Going straight to the source means no social media filtering, and you can select the stuff YOU want to see, directly.

Got Your Own Solution?

Let us know! We want to hear from you – we know you’ve got great ideas and opinions, as you send us feedback every day. It’s great. Connect with us on our social media, or email us at [email protected].