By Nicole Saldarriaga

By Nicole SaldarriagaThere were many things an Ancient Greek could fear. After all, there were capricious and vengeful gods to appease, and no small list of monsters and mythical creatures to haunt their nightmares. However, there is one being that many Ancient Greeks feared most of all—in fact, most people wouldn’t even dare to speak his name or the name of his horrifying realm—Hades and his underground Kingdom of the Dead.

This seems like a no-brainer, right? If there’s anything that human beings seem to fear (whether they do so consciously or not), it’s death. It’s no surprise that Hades, as the god of death, would not only be feared but also avoided as much as possible. Other than a few noteworthy exceptions, Hades—unlike his divine brothers and sisters—was not depicted much in ancient artwork, did not have many temples constructed in his name, and was generally not worshipped as regularly or by as many people. I mean, if you find it terrifying even to say a god’s name, it may understandably be difficult to hold feast days in his honor.

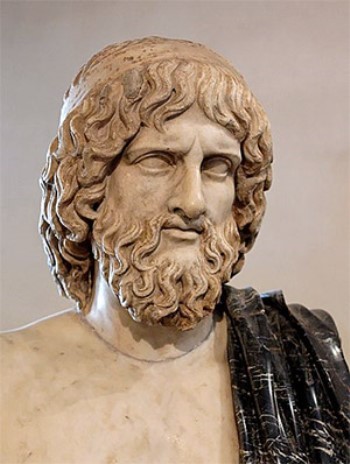

Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades

Zeus, Poseidon, and HadesAll told, this may seem like just another example of Hades drawing the short stick—and in this case that’s not an idiom. After Zeus forced his father, Cronos, to disgorge Zeus’ brothers and sisters (whom he had swallowed in order to circumvent any threats to his power), and after Cronos’ children overthrew his rule as supreme god, Zeus and his two brothers—Poseidon and Hades—drew lots to decide which realms they would rule. Normally, according to Greek law, the eldest brother (which in this case was Hades) would have been granted the biggest and best kingdom; but Hades was cheated out of his rightful place and title as king of the gods by the drawing of lots (though it seems like an arbitrary system, it was a customary solution to difficult decision-making issues). He drew the shortest stick, and therefore had to accept the twisted, dark, Underworld as his realm while his youngest brother became king of the gods and erected his kingdom in the sky. Top that off with the fact that most people were too afraid of him to worship him, and it seems like the eldest of the Olympians got a pretty rough deal.

Cerberus, Hades’ guard-dog

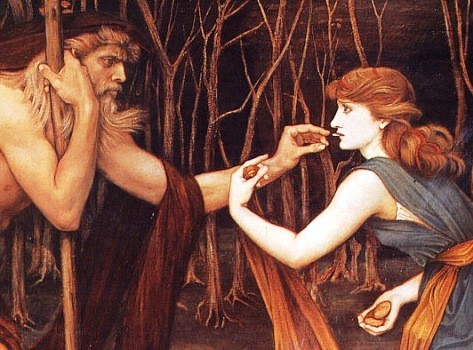

Cerberus, Hades’ guard-dogOn some level it’s easy to understand why Hades wasn’t very well liked as a god, or at least why the Ancient Greeks would have wanted to keep him at a distance. As ruler of the Underworld, he was heavily associated with death (though he is not Death incarnate—there was another god for that, named Thanatos), and your average mortal human isn’t usually comfortable thinking about death too seriously. The Ancient Greeks in particular had a lot to fear from death. The Underworld was a notoriously harsh place full of terrifying creatures like Cerberus, Hades’ three-headed guard dog, the grotesque Furies, and the Hekatonkheirs (giants which had one hundred hands and fifty heads), just to name a few; and while the Underworld did include a paradise called the Elysian fields, that balmy and beautiful place was reserved for only the most heroic of figures. Everyone else ended up in the Fields of Asphodel—a grey and uninteresting limbo where the shades of the average Joes and Janes wandered aimlessly for all eternity—or in Tartarus, where the evil were punished for their behavior in life by some truly creative methods of torture.

Even more terrifying to the average Ancient Greek was the way in which death could affect the world of the living. Not only was the death of a loved one associated with the pain of loss and loneliness, but it was also riddled with anxiety. Customary burial rites were very specific and important—it was believed that performing them incorrectly could lead to disaster for both the spirit of the deceased and for those left behind.

A popular example of this is that of the coin placed under the deceased’s tongue or on their eyelids. This coin was payment for Charon, the ferryman of the Underworld who took the shades of the newly dead across the River Styx and into the Underworld proper. If a shade had no coin with which to pay Charon, he would not be allowed to cross the Styx, and would never make it into Hades’ kingdom—instead he or she would be forced to wander the earth restlessly and might even haunt those who failed to perform the proper burial rites. This was a terrifying prospect for the Ancient Greeks, who not only wanted to avoid being haunted, but who also believed that the continual presence of shades on earth could actually drain life out of the living.

A popular example of this is that of the coin placed under the deceased’s tongue or on their eyelids. This coin was payment for Charon, the ferryman of the Underworld who took the shades of the newly dead across the River Styx and into the Underworld proper. If a shade had no coin with which to pay Charon, he would not be allowed to cross the Styx, and would never make it into Hades’ kingdom—instead he or she would be forced to wander the earth restlessly and might even haunt those who failed to perform the proper burial rites. This was a terrifying prospect for the Ancient Greeks, who not only wanted to avoid being haunted, but who also believed that the continual presence of shades on earth could actually drain life out of the living.Clearly, there was a lot to fear in death; and Hades, as the King of Death, was not the most beloved figure in ancient mythology. However, with fear comes a certain amount of respect, and in many ways the dark and gloomy Hades got a lot of it.

Archeologists have found the ruins, located in the Greek town of Eleusis, of at least one temple that may have been dedicated to Hades and his queen, Persephone. Historical records indicate that though it did not happen as often as it did for other gods, Hades was, on occasion, ritually worshipped, and with a great deal of servile deference. Those who prayed to Hades would bang their hands or even their heads against the ground in order to get his attention, worshippers would avert their eyes or turn their whole heads away from statues and altars while making sacrifices of beautiful black animals, and special pits were dug in which the sacrificial blood was poured so that it would reach Hades more easily. After a while, because his proper name would not be spoken, Hades was referred to as Plouton, closely related to the Greek for “giver of wealth,” because he was thought to be responsible for the precious minerals found in the ground—he was thus venerated for a time as a god of wealth as well as a god of the Underworld.

Archeologists have found the ruins, located in the Greek town of Eleusis, of at least one temple that may have been dedicated to Hades and his queen, Persephone. Historical records indicate that though it did not happen as often as it did for other gods, Hades was, on occasion, ritually worshipped, and with a great deal of servile deference. Those who prayed to Hades would bang their hands or even their heads against the ground in order to get his attention, worshippers would avert their eyes or turn their whole heads away from statues and altars while making sacrifices of beautiful black animals, and special pits were dug in which the sacrificial blood was poured so that it would reach Hades more easily. After a while, because his proper name would not be spoken, Hades was referred to as Plouton, closely related to the Greek for “giver of wealth,” because he was thought to be responsible for the precious minerals found in the ground—he was thus venerated for a time as a god of wealth as well as a god of the Underworld.It would seem, then, that despite Hades’ slightly unpopular reputation, he was never completely forgotten or ignored. The Ancient Greeks may have feared death and the Realm of the Dead in the extreme, but that also means that when they did have to address death, they were incredibly respectful of its power. It was, no doubt (and perhaps still is), an intensely complicated relationship with our own mortality. So maybe Hades didn’t get the rawest deal after all—he was the god of that thing that all of us fear (even if only slightly), that thing that keeps us up at night, that thing that has inspired countless philosophies which are supposed to release us from the fear of its grip. To some extent, humans never stop talking about death or the afterlife.

Maybe the eldest Olympian got the biggest kingdom after all.

One comment

Hi,

Many thanks for this. I also heard it on the History Author Show podcast which I really enjoy. I’m wondering though how is it that Hades also seems to be the underworld, along with being an ancient Greek god? All the other gods were just gods e.g. Apollo, Zeus, etc yet Hades seems to be the god of the underworld and the entire underworld itself. Is it that this is a common mistake that just creeped into our understanding over the centuries and made life easy for people like myself, being part of the ‘great unwashed’, as there seemed to be a few parts to that underworld (Elysian fields, Asphodel and Tartarus) or would you know of another reason why Hades also seems to be known as a location?

Kind regards,

Michael

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.