By Ben Potter

It’s been often said that what was good about the Romans came from their cultural forefathers, the Greeks.

Like most (I refrain from saying ‘all’) generalisations, there are grains of both truth and falsehood to this claim.

Whilst there may well be startling similarities between Greek and Roman art, gods, drinking habits, sexual conduct and empire building, these are nothing compared to the parallels between the two cultures’ comedic theatre.

In this respect, the man we turn to in order to sample our very first taste of Roman literature, is the playwright Plautus.

As the world expert in the field, P.G. McC. Brown, put it:

“Latin literature begins with a bang, with a dazzling display of virtuoso verbal fireworks in twenty comedies written by Plautus between about 205 and 184 BC”.

And the fact that he borrowed a plot or two (or 130 according to some sources) does nothing to diminish Plautus’ status as the first and, many say, best exponent of Roman Comedy.

But before we dive headfirst into those literary waters, a quick biographical note (such as posterity enables us to provide).

Plautus hailed from Sarsina in Umbria, near modern day San Marino, and his journey to theatrical greatness is an unusually cyclical one.

The story goes that the young Plautus was originally some sort of stage-hand or set designer whose artistic curiosity eventually encouraged him to try his hand at acting.

After what must have been a moderate success, he’d saved enough money to abandon this disreputable pursuit (actors were not well thought of in Roman society) and invested everything in a maritime business.

As great as he was, Plautus was no entrepreneur. He lost his entire fortune and was reduced to working as a mill-hand by day and studying Greek comedy by night.

While this life of relative poverty and menial employment would suggest Plautus did not have a privileged upbringing, the very fact that he was extremely literate in both Latin and Greek means that this is no rags-to-riches story. To prove this point further, he was very knowledgeable of both nations’ politics and history, well-versed in poetry, and extensively well-read.

Even so, Plautus’ studious approach to the Greek practitioners of his art meant his knowledge bordered on the comprehensive, rather than merely the extensive.

Interestingly, his playwright of choice was not the master of Old Comedy, Aristophanes, but a figure who dominated New (Greek) Comedy… Menander (342-290 BC).

Menander’s brand of humour was much less fierce and acerbic than that of Aristophanes. While it was obvious he did engage in political satire and playful bawdiness, he never quite touched the subversive or perverse extremes that Aristophanes regularly reached.

He also liked to pepper his works with easily digestible, homespun maxims which must have made him one of the more easily quotable artists of the age.

These examples give us a flavour:

“Evil communications corrupt good manners”

“Whom the gods love die young”

“The property of friends is common”

Perhaps it was for this reason that Plautus chose Menander as his main influence rather than Aristophanes. Or maybe it was because Menander was closer in time than the Old Greek Comic… or that they were the only books Plautus could get his hands on.

Whatever the reason, the great Greek (and his contemporaries) had more than a little ‘influence’ on the Latin scribe.

Not that plot pilfering was either looked down upon or kept a secret.

In fact, in several of Plautus’ prologues he openly provides the original Greek title and author of the plays he has translated. While this was not always the case, we can safely assume that his intentions were not deceitful in this respect.

So blatant was this that originally it had been assumed by many that Plautus was much more a linguist than a true poet. But in 1968, the discovery of Menander’s original play, Dis Exapaton (The Double Deceiver), shed light on Plautus’ methods. It was from this script that his Bacchides (the Bacchis Sisters) was adapted.

Though the broad plot and sequencing are much the same, Plautus cuts a couple of scenes, changes the order of others and tweaks the stage directions here and there.

He also adds and cuts jokes as he sees fit, inserts or enhances puns (his favoured method of comic delivery) and changes the characters’ names.

This was about all that was required of Plautus in terms of characterisation, as both New Greek Comedy and Roman Comedy almost entirely relied on stock characters, e.g. the love-struck young man, his miserly father, the wily, manipulative slave, and the appetitive parasite to name but a few.

One thing Plautus did not do, surprisingly for us perhaps, is change the setting of the play from Athens to Rome.

While the Greek setting of Plautus’ plays is fascinatingly paradoxical for us, it would have been seen as mundane to the average Roman. This is because Plautus didn’t actually write ‘comedies’, he wrote fabulae palliatae (dramas in a Greek cloak).

This framework allowed for much artistic and comedic license on the part of the writer, as Roman in-jokes could be used in an abstract setting for comic effect. Indeed, the fact that ‘going Greek’ was a stock phrase to denote debauchery and excess tells its own story.

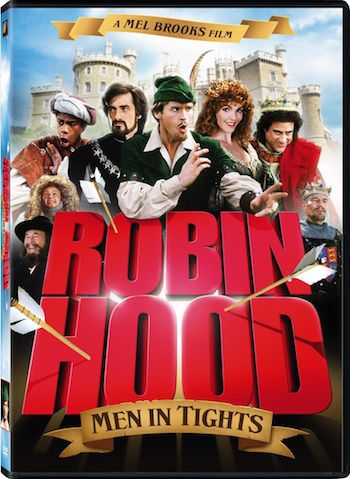

A modern parallel could be something like Blazing Saddles or Robin Hood: Men in Tights, as these movies tell us more about contemporary America than their respective historical periods.

Similarly, Plautus’ work is full of risqué and compromising situations, along with slapstick and a penchant for randomly inserting a musical number. However, as a poet and an artist, Plautus clearly had a lot more to offer than the impressively endless gag-reel for which he is famed.

His loftier side shines through in his cantica. These highly stylised and impressive arias seem almost capriciously inserted (often early in a play) and presumably serve the dual purpose of captivating the audience’s attention and showing off the true skill of the writer.

Indeed, Plautus’ contemporary legacy was an impressive one; his plays were still being performed in Rome up until the time of Horace (65-8 BC).

He was also popular in Renaissance Italy, especially after 1429 when 12 of his plays, presumed lost forever, were unearthed in Germany.

That said, his stock plummeted dramatically from the 17th century onwards.

It would not be hard to imagine that this was true in England because he was, well, replaced. It was during this period that Shakespeare did to Plautus what Plautus had previously done to Menander.

In the end, there is no better summary of Plautus the comedian than what given to him as an epitaph. Unlike many a great man, he was fortunate enough to have his immortal legacy suitably reflect the scope and splendour of his art:

Postquam est mortem aptus Plautus, Comoedia luget,

Scaena est deserta, dein Risus, Ludus locusque

Et Numeri innumeri simul omnes conlacrimarunt

Plautus is dead, and on the empty stage

Sad comedy doth lie

Weeping the brightest star of all our age

While artless Melody

And Jest and Mirth and Merriment forlorn

Their poet mourn

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.