By Anya Leonard

“We passed along the coastline of Epirus

To port Chaonia, where we put in,

Below Buthrotum on the height…

I saw before me Troy in miniature

A slender copy of our massive tower,

A dry brooklet named Xanthus…and I pressed

My body against a Scaean Gate. Those with me

Feasted their eyes on this, our kinsmen’s town.

In spacious colonnades the king received them,

And offering mid-court their cups of wine

They made libation, while on plates of gold

A feast was brought before them.”

– Virgil, The Aeneid (Book III 388- 482)

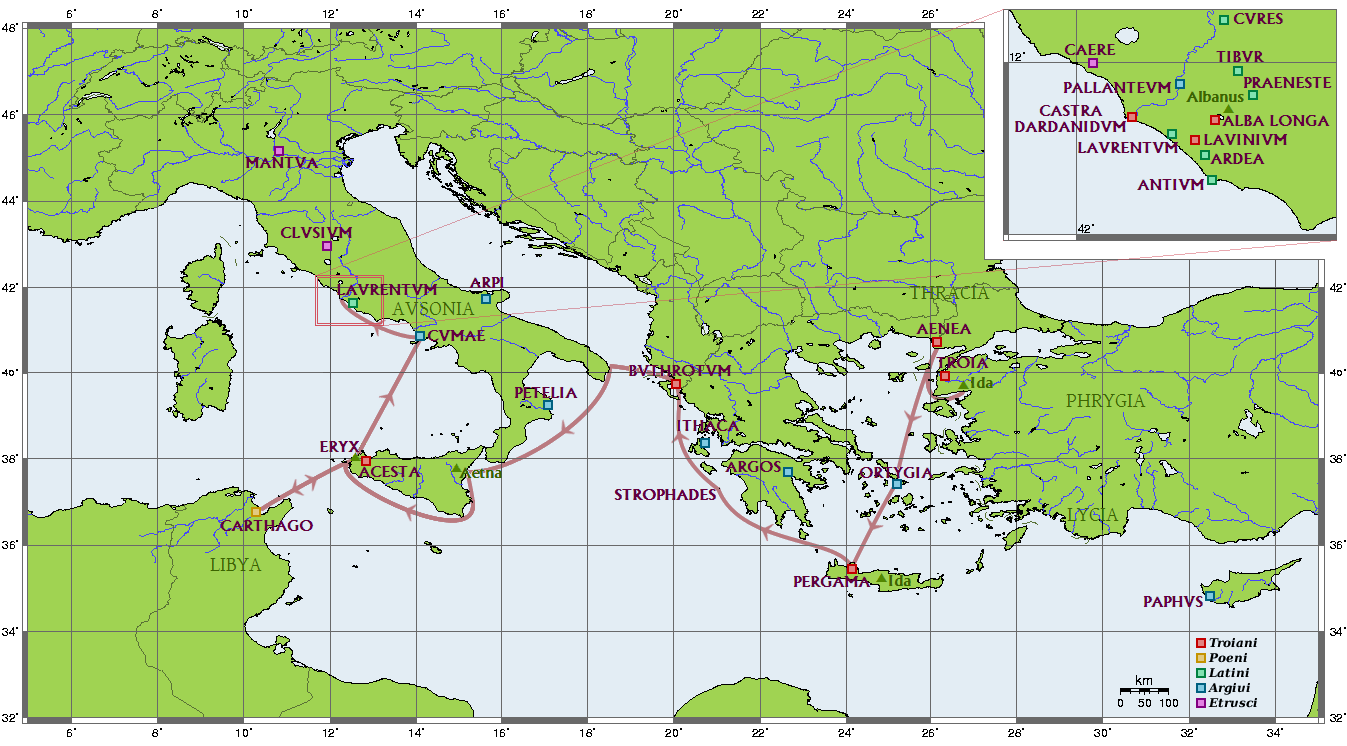

Aeneas was quite surprised, you see. When Virgil had him utter those words above, the Trojan hero had been already traveling for some time and over great distances… so you can understand why he may have been a bit aghast when, arriving at Buthrotum, he found a miniature Troy, complete with familiar kin.

But why were there Trojans on what is now Albania’s coast, so far away from their homeland?

It all happened after the fall of Troy, when the fleeing seer Helenus, son of king Priam of Troy, and Hector’s widow, Andromache, stopped in Epirus. They decided they should sacrifice a bull, but as it turns out, the animal had alternative plans. The beast escaped, swam across the gulf and then immediately died upon reaching the other side. Helenus saw this as an auspice and founded the new city where the bull expired, naming it Buthrotum, or ‘wounded ox’.

When Aeneas arrived, therefore, he had a fruitful pit stop along his fateful journey. Not only was he able to rejoin friends and family, he also received a far-reaching prophecy… one that you might say, sort of makes the book. Essentially, he learns he has a planned, divine destiny that includes seeking out Italy, which his descendants will one day rule.

At least that’s how Virgil describes it…

So, you can see then why the Romans, Aeneas’ alleged progeny, might like the place. In fact, this mythological sea town, strategically located by the straits of Corfu, became a not so inconvenient real life destination for the rich and famous of Ancient Rome.

Caesar first thrust the then small settlement into the Roman spotlight in 44 BC, when he designated Buthrotum as a colony to reward soldiers who were loyal to him against Pompey. However, Buthrotum received only a meager number of colonists due to local landholders’ objections, in particular Cicero’s friend, Titus Pomponius Atticus.

Then in 31 BC Buthrotum’s growth was renewed, this time by the Emperor Augustus, fresh from his victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium. During this time, the town’s size doubled, and expanded to include an aqueduct, a Roman bath, houses, a forum complex, and a nymphaeum.

The popularity of the place, including its legendary and powerful summer guests, was in no doubt. The statues and inscriptions found within the city center offer ample evidence for this. For a brief period, the people who shaped the future of Rome took a very personal interest in Buthrotum, along with her shimmering clear blue waters.

But if Rome wasn’t built in a day, neither were her colonies…

Originally a town within the region of Epirus (as described in the quote from The Aeneid), Buthrotum was a major center for the Chaonians, an Ancient Greek tribe. These people had close contacts to the Corinthian colony of Corcyra (modern day Corfu), evidenced by Proto-Corinthian pottery of the 7th century and then Corinthian and Attic pottery of the 6th century. However, the earliest archaeological proofs of settled occupation date to between 10th and 8th centuries BC.

Buthrotum’s location and access to the straits developed its trade and importance, and by the 4th century BC, the settlement included a theatre, an agora, as well as a sanctuary to Asclepius. This latter feature attracted worshippers from around the region, pilgrimaging, with symbolic objects and money, to the sanctuary in order to be healed. In fact, the sacred powers of Buthrotum’s waters were revered as long as the town lasted.

Eventually, the settlement was large enough to warrant protection. Around 380 BC it was fortified with an 870 meters long wall and five gates. All up, it enclosed an area of four hectares. Many of these walls can be still seen today, illustrating fine craftsmanship, featuring reliefs with a lion eating a bull.

Then, as we already know, the Romans became involved. Buthrotum became a Roman protectorate, alongside Corfu, in 228 BC, but was increasingly dominated by the Romans after 167 BC. In the next century, it became a part of the province of Macedonia.

This, more or less, brings us up to speed to the time of Caesar, then Augustus and Virgil’s description of Buthrotum in The Aeneid.

—————————————-

The Makings of a Myth…

What truth lies in Virgil’s ancient telling of the town? Well, it turns out, not much.

While there have been objects that archaeologically date back to the Bronze Age within the region, nothing as yet has been found at Buthrotum. This doesn’t necessarily mean the town didn’t exist back then…. However, it may not be surprising to hear that there were certain incentives among rulers to suggest that it did.

After all, Virgil’s story is arguably very poetic propaganda for the Emperor Augustus, a way to connect his lineage back to the mythological greats. It seems that this wasn’t a new trick.

Indeed, it could be that Buthrotum’s association with Troy was developed as early as the 5th century BC by the Molossian Royal family. Back then, Epirus (the original region) was taken over by the Molossian tribe… and they wished to promote their status as having both Greek and Trojan ancestry.

The story went as follows: Their eponymous ancestor, Molossus, was supposedly the older son of Pyrrhus Neoptolemos, the child of Achilles and Andromache (Hector’s wife). Later on, his descendent, the Molossian King Pyrrhus of Epirus, choose to favor the Greek Achilles as his ancestor, in order to reinforce his familial links with Alexander the great. Apparently he was too young to serve with the Macedonian general so he used this PR effort to up his standing… well, that and establish himself as a natural opponent of Rome!

Despite his efforts, Pyrrhus of Epirus in the end was remembered more for his ‘Pyrrhic victories’ than his mythological genealogy.

The town of Buthrotum, meanwhile, continued to maintain a fairly quiet, modest existence… that is until drawing the attentions of Caesar, and later the emperor Augustus, in the middle of the first century BC.

This makes us wonder then, dear reader, why did Caesar, and then more so Augustus, choose to highlight Buthrotum? Could it be that they were trying to connect themselves to the mythology as well? Or did Virgil write Aeneas’ journey his way to reinforce Augustus’ (and by association Caesar’s) choice in colonies?

Or could it be simply, with its sandy beaches, handy waterways, access to the Corfu straits and natural defenses, that it was not only a beautiful place to spend one’s time, but also a very strategic one?

Backing up this latter theory, we must refer to the famous roman politician and orator, Cicero. In fact, much of what we know of Buthrotum’s history in this period actually comes from his letters. As mentioned, Cicero’s friend, Atticus, who owned an estate near Buthrotum, was concerned at the potential loss of land associated with the arrival of the colonists and lobbied against it. Although Atticus’ half of the correspondence is lost, Cicero’s replies provide a fascinating insight into the moment when Buthrotum briefly figured on the political stage of Rome itself.

He writes:

“Let me tell you that Buthrotum is to Corcyra (Corfu) What Antium is to Rome – the quietest, coolest, most pleasant place in the world” – Cicero Letters to Atticus 4.8.1 (56BC)

We will never be certain of Buthrotum’s ancient, ancient past, nor the rulers’ motivations to connect with it… But standing on our final ferry trip, back to Corfu, we watch Albania’s gentle coast fade with the sunset… and know exactly what Cicero was talking about.

One comment

Wonderful article of a fabulous location. I teach the Aeneid and visited Butrinti this summer. I can see why it was such a perfect location for a settlement. I don’t know if anyone has notices but the flora makes it very fragrant. Great place…worth the trip!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.