Seven warriors killing seven other soldiers in front of seven gates. You’d think that story would forever condemn the number to enmity. But Aeschylus’ Seven Against Thebes makes no comment on the conspicuous symmetry of the legend’s numeral element. Maybe the seven city portals warranted warriors to both attack and protect them. Unfortunately if you are seeking legitimacy in the next installment of the Oedipal series, you probably won’t find it. In fact, the seven Theban gates have never been found. This would lead us to believe that the number was entirely made up… Or stolen from a different story.

We can’t know for sure, of course, but there are some pretty eerie parallels between Seven Against Thebes and a little old myth found in an Akkadian epic text. It’s a story of Erra the plague god, and the Seven (Sibitti), called upon to destroy mankind, but who withdraw from Babylon at the last moment. Does this sound like Aeschylus’ Seven against Thebes?

It is a play that has only a few action points, but ones that match quite closely to the Fertile Crescent edition. Of course with the Greek adaptation, there’s a thorough back story regarding an infamously unlucky king.

In Seven Against Thebes, poor Oedipus is long gone, but his bad luck isn’t. His unfortunate descendants have inherited his prejudicial fate. The same destiny that brought the ruined royal to bed his ma and slaughter his pa, now drives his two sons to destroy each other.

We saw this coming in Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus when son number one, Polynices, came out of the wood works begging his blind father to help him out. The heirs were suppose to split the throne, alternating years in power, but offspring number two, Eteocles, refused to play nicely. He exiled his older brother and greedily grabbed the Kingdom of Thebes for himself. Oedipus told his son to buzz off and leaves him with this curse: The two boys will fall from each others’ sword.

This is where Seven Against Thebes begins. Polynices, with a severely bruised ego, amasses a foreign army to take back his hometown. This act of attack immediately assigns the elder child into the ‘villain’ character, rather than the selfish younger son who kicked him out in the first place.

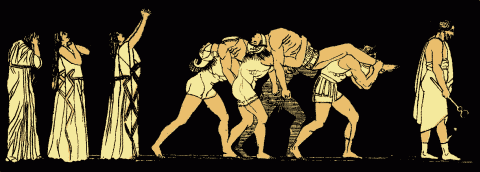

And so, Aeschylus writes Eteocles as his hero. We only see the story from his side. The play begins with him, the current Theban king, listening to a spy describe his brother’s oncoming army. Eteocles then assigns his own soldiers to each of the seven gates to combat their counterparts.

The reader falls into the rhythm of impending doom. The chorus bewails the women, who will be taken as slaves if the city falls. Eteocles tells the ladies to stop crying and deal with it. The modern reader may wonder why we are suppose empathize with this character.

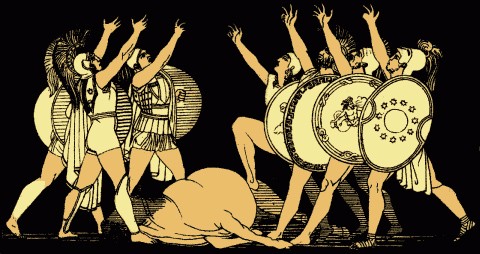

Eventually king, spy and chorus discuss the last warrior. It is the brother Polynices. Fulfilling destiny, Eteocles appoints himself as the seventh combatant. Oedipus’ final malediction come true as, sure enough, the two brothers kill each other. Fortunately for the city’s inhabitants, the war does not continue without each army’s leader.

In the original version, the drama comes to end when the boys’ bodies are brought on stage to a mourning chorus. In the Sophocles compatible edition, written 50 years later after the success of the subsequent play, a messenger appears and announces a prohibition against burying Polynices. Then, as a perfect lead in to the last installment of the Oedipal series, Antigone, the rebellious daughter announces her intention to defy this edict.

So what can we attribute to Aeschylus? Is the story original or just the manner of the storytelling? The ‘mytheme’, the original, unchangeable element, is of the horrible seven bringing potential devastation, which is prevented at the very last minute. This concept traditionally seems to be based on Bronze Age history in the generation before the Trojan War. You can see it in the Iliad’s Catalogue of Ships, where the only remnant Hypothebai (“Lower Town”) subsists on the ruins of Thebes.

But Aeschylus did do something very unique. He added another character. To us now, that may not seem very impressive, but at the time it was completely revolutionary. Previously, the chorus danced around a glorified orator. Then the “Father of Tragedy” came onto the stage, and there was interaction, tension, conversation and essentially the real beginning of drama.

Seven Against Thebes was written by Aeschylus around 467 b.c. The trilogy won the first prize at the City Dionysia. Its first two plays, Laius and Oedipus as well as the satyr play Sphinx are no longer extant. You can read the full story here:https://classicalwisdom.com/greek_books/the-seven-against-thebes/

Make sure to read the next installment of the Oedipal myth for next week’s essay. We’ll go back to Sophocles to read his renowned version of Antigone. You can view the whole text here for free: https://classicalwisdom.com/greek_books/antigone-by-sophocles/

2 comments

I just want to tell you that I am just very new to weblog and truly loved your web page. Almost certainly I’m likely to bookmark your website . You surely have impressive articles and reviews. Kudos for sharing your web site.

I do sympathize with Eteocles, though I am female. He just reminds the women what their civil duty requires, i.e. not to undermine the morale of defenders of Thebes by continuous whining. He is often called misogynist. Actually, it would be misogynist not to require the women to stop crying, because it would mean equating women with infants who cannot be stopped from crying. Eteocles instead treats the Chorus as responsible adults, and they start behaving as such.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.