By Ben Potter

Archaic. Classical. Hellenistic. These terms are often (and quite naturally) conflated together under the generic heading of ‘classical’, or, at the very least, ‘old’. It appears that organizing history into clear, distinct eras can be a tricky business.

This, of course, is more true for the Greeks than for the Romans.

This is because it’s relatively easy to get one’s head around the fact that the Romans smoothly traversed the ages from Monarchy to Republic to Empire. (Obviously there are many more nuances to the situation than that – but let’s save those for a later date).

In contrast, the Greeks were not one ‘people’, but a series of distinct, if similar, factions (Athenians, Spartans etc). As such, they have fewer common events that can be used to separate periods in their history.

This, however, doesn’t stop us from trying…

So, let us delve head first into the past in order to try to understand the various ages and epochs of Ancient Greece…

Prehistoric Greece

Classicists usually divide prehistoric Greece into the Stone and Bronze ages.

The Stone Age is chiefly remarkable for establishing the foundations of Greek farming (including viticulture) and can be further eroded into three periods: the Palaeolithic (9000 BC and before), Mesolithic (9000-7000 BC) and Neolithic (7th-4th millennia BC). It was during this last age that metallurgy began to take root and ushered the Ancients into the Bronze Age.

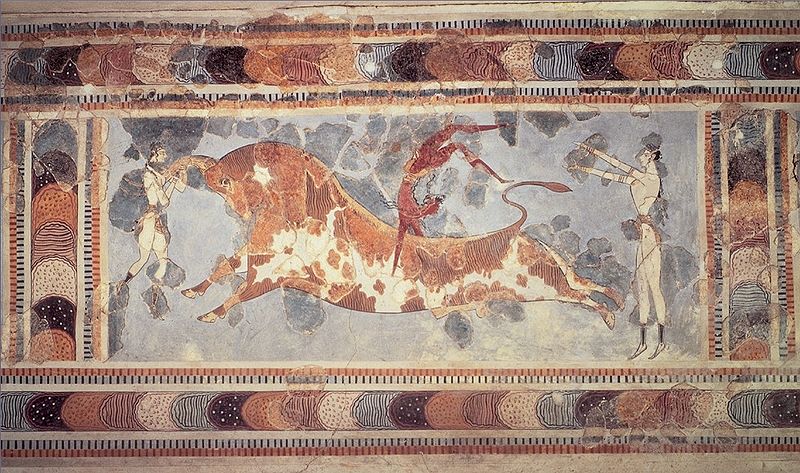

It was then, in the Bronze Age, that we saw the prevalence of the bull-fancying Minoan civilization of Crete (c.3500 BC).

Some argue that the Minoans were never true Greeks, as they probably did not communicate using the Greek language. However, as their civilization paved the way (at least on Crete) for the Mycenaeans, who did speak Greek, they are impossible to remove from the equation.

And language, or its absence, is precisely what marks both the end of the Mycenaean period and the end of the Bronze Age.

It has been posited that these well-organised proto-Greeks fell foul of invaders, migration, natural disasters or even climate change!

It cannot be known for sure which of the above rang the death knell for the civilization that conquered Troy (c.1200 BC – if it happened at all), but what is clear is that the written language of the time, Linear B, died along with them. Thus we are shepherded into the Greek Dark Ages (c.1100-776 BC).

The Dark Ages

In addition to the loss of written language, Greek communities became more isolated in this time. And despite a dearth of information on the age, we can list one great highlight which was an inadvertent result of the absence of uniform literacy; the rise of the oral tradition.

It is from this that the yarns of Homer, so influential on the art and literature of the next 3000 years of European civilization, were spun.

The Archaic Age

It began in 776 BC. The twin date of the first Olympics and the end of the Dark Ages at first seems nothing more than a useful, but arbitrary milestone.

While this is very nearly true, it symbolically ushers in an age in which Greeks were no longer strangers to one another. Rather, they were engaged in reciprocal political, commercial and, in this case, sporting activity.

More than this, it was c.776 BC when iron replaced bronze, a new alphabet (borrowed from the Semites of the East) emerged, and the Greeks began to extensively and systematically colonize.

These advances were concurrent with the development of the polis, the Greek city-state.

Indeed, the Archaic period gave rise to everything we identify with as being broadly ‘Ancient Greek’, including gymnasiums, symposiums, sculpture, architecture, festivals, athletics, drama, homosexuality, religion and even war.

It is this last point which is the most unusual. Greeks began to recognise each other as the same ‘nationality’ and, as such, a collective consciousness developed regarding the rules of engagement (or, perhaps, vice-versa).

This curious phenomenon of brothers-in-arms being brothers-at-arms is best exemplified by its exception, i.e. The Persian Wars (492-490 BC and 480-479 BC).

Another remarkable aspect of the Archaic period is thought to have come about via warfare, or specifically from hoplite (heavily-armed infantrymen) warfare; tyranny.

While Argos and Corinth succumbed early to tyranny, Sparta managed to avoid it until Hellenistic times. Athens, too, tasted it in the latter half of the century, despite Solon’s reforms of 594 BC which paved the way towards democracy. However, the Athenians managed to overthrow that tyranny within a generation.

The Classical Age

If the Archaic Age established who the Greeks were, the Classical Age (510 BC or 480 BC – 323 BC) really cemented why they are remembered so fondly.

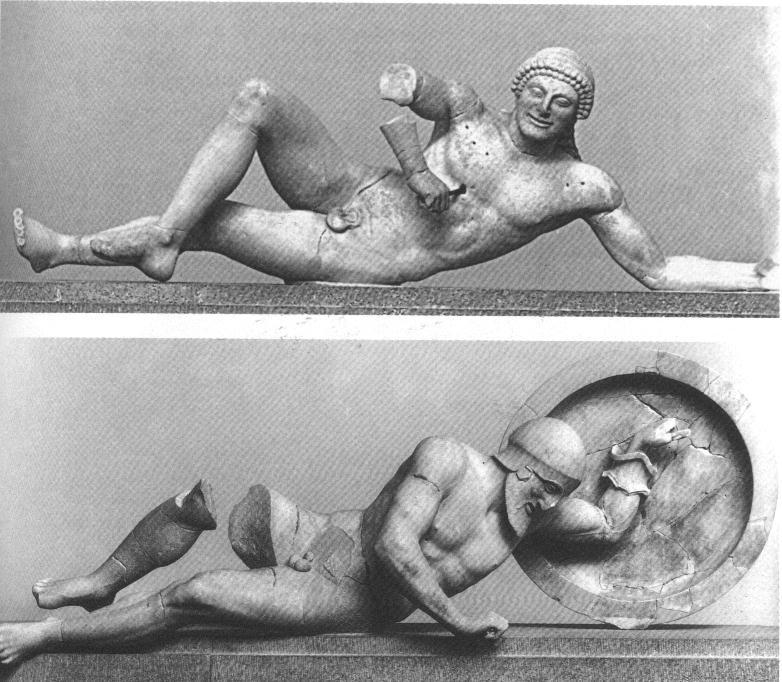

Indeed, one of the biggest distinctions between the two eras is the rise in artistic talent.

This is perfectly exemplified by the pedimental sculptures on the temple of Aphaia at Aegina. The west pediment shows the more clumsy sculptures of the archaic period and the east displays the newer, more sophisticated techniques of the classical era.

Additionally, this sensational period of artistic and intellectual fecundity gave rise to a plethora of remarkable men. There was Phidias (the genius behind the Parthenon), the sculptors Myron, Praxiteles and Polyclitus, philosophers like Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, and the great playwrights Aeschylus (also active in the Archaic period), Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes… not to mention the historians Herodotus and Thucydides.

The commonly accepted date for the start of this period (480 BC) saw the Greeks repelling the Persians from their soil. In fact, it was war, every bit as much as art, that went into defining the Classical period.

The Greek-on-Greek Peloponnesian Wars (461-446 BC and 431-404 BC) were very much business as usual. Then the entire nation, along with Egypt, Persia, Afghanistan and India, was brought under the yoke of Alexander the Great.

The Great man’s death in 323 BC signalled the end of the Classical period and the beginning of the Hellenistic age.

The Hellenistic Period

The post-Alexandrian scuffle saw a variety of kings (who identified themselves as Greek) fighting each other and their neighbours on the edges of the civilised world.

With this whirlwind of power-mongering going on around them, the actual Greeks themselves split into various confederacies: the Boetians, Arcadians, Achaeans and Aetolians.

It was at this time that Roman eyes were drawn eastwards thanks to Illyrian piracy in the Adriatic Sea… a problem promptly quelled by the developing superpower.

Roman interest in the Greek world became critical when King Philip V of Macedon allied himself to Rome’s very own version of Osama Bin Laden: Hannibal of Carthage.

The Hellenistic age came crashing to an end in 146 BC when Rome defeated the doomed resistance offered by the Achaean Confederacy. In doing so, they utterly obliterated the ancient city of Corinth and enjoyed complete hegemony over Greece.

The Roman Period

From this point onwards Greek power, as something tangible and autonomous, was more or less nil. Her influence, however, remained – if solely because of her intellectual and cultural reputation.

Though it seems a sad, whimpering end to a great chapter of world history, it should be remembered that this reputation, forged in the mania of the Archaic period and brought to fruition in the splendour of the Classical age, did not die. Indeed, it continues to inspire, educate and amaze, and has not yet, and hopefully never will, fade away.

One comment

It’s amazing how something with potential takes thousands of years to build up before it peaks for a few hundred years just before it is lost and whatever good came out of it becomes someone else’s…

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.