By Ben Potter

“Quick, bring me a beaker of wine, so that I may wet my mind and say something clever”.

In one witty aside the Athenian comedian, Aristophanes, has embodied the modern feeling towards the Greeks and the grape.

To us, it seems like a beautiful partnership that helped build the foundations of our modern world. We see that versatile fruit’s superb elixir as not merely essential for trade, religion, and social interaction, but also as a stimulant of genius; a necessary catalyst for intellectual enlightenment.

And drunkenness was commonly seen, sculpted, talked and written about in the Greek and Roman worlds… as both a force for good and evil.

In the Odyssey we see the damaging effect undiluted wine has on the Cyclops; dulling the monster’s sensibilities and thus allowing Odysseus to blind him.

Additionally, one of Odysseus’ crewmen, Elpenor, passed out on a rooftop in a drunken stupor, only to fall off it and die first thing in the morning.

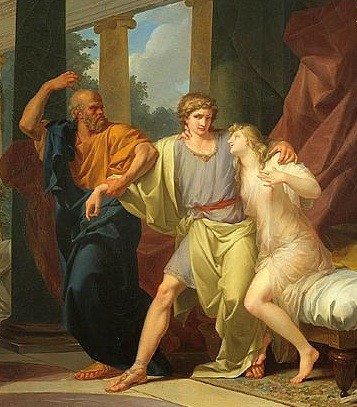

Alcohol is also blamed as the cause of the long-standing grievance between man and centaur, resulting in their chief trying to make off with (often interpreted as ‘rape’) a human bride at her wedding:

“Wine is many a man’s undoing, when he gulps his draught and will never drink discreetly. Wine it was that darkened the wits of Eurytion the Kentauros in the palace of bold Perithoos… from this beginning came the long feud between men and Kentauroi”.

While the Greeks didn’t exactly define ‘alcoholism’, they did recognise that certain people were predisposed towards dipsomania… and were rarely polite about them.

“And what do you say of lovers of wine… they are glad of any pretext of drinking any wine”.

The fact that these words from Plato’s Republic are presented as self-evident speaks to some level of the social struggle with the demon-drink.

Aristophanes gives us evidence of this in his Wasps when a law-abiding, but avaricious old geezer shows his truly reckless and pernicious side… when under the influence of alcohol.

Unfortunately Aristotle’s On Drunkenness has been lost, but if the form book is anything to go by, it was not a treatise on the benefits of letting one’s hair down.

That said, Herodotus does little to condemn the reported practice that the Persians would only ratify an important decision when it had been agreed upon both sober and drunk. He does state, however, that vomiting and urination in the presence of another man were prohibited… which might restrict many people’s university experiences.

Abstaining was championed here and there, though whether this is just not indulging in a hair of the dog or being genuinely teetotal, is still a bit unclear. We personally suspect the former, as it seems it would have been impractical to fully absent oneself from the wine-cup, so pervasive was it to all levels of society.

Indeed, there were some concerns regarding the effects of alcohol on children. Plato (who seems to have had rather a lot to say on the subject) suggested 18 as a suitable age (i.e. manhood) at which a man should start drinking.

Despite their reputation for both sexual and alcoholic orgies, the Romans were at least as equally (and perhaps more) well versed on the dangers of over-indulgence.

Indeed, they had much more of an idea of being unremittingly plastered in a manner we, today, would clearly recognise as alcoholic.

Pliny the Elder paints a gruesomely poetic picture:

“the drunkard never beholds the rising sun, by which his life of drinking is made all the shorter. From wine, too, comes that pallid hue, those drooping eyelids, those sore eyes, those tremulous hands… sleep agitated by Furies… dreams of monstrous lustfulness and of forbidden delights… the annihilation of the powers of memory… while other men lose the day that has gone before, the drinker has already lost the one that is to come”.

Seneca believed the manly pursuit of drunkenness was not merely damaging to the individual, but to the state. He left no doubt as to whose talent was well and truly wasted:

“Mark Antony was a great man, a man of distinguished ability; but what ruined him and drove him into foreign habit and un-Roman vices, if it was not drunkenness… continued bouts of drunkenness bestialize the soul… the habit of madness lasts on, and the vices which liquor generated retain their power even when the liquor is gone.”.

Likewise, Lucretius (generally a bit of a kill-joy in most matters) states:

“when the strong wine has entered into man, and its diffused fire gone round the veins, why follows then a heaviness of limbs, a tangle of legs… a stuttering tongue, an intellect besoaked… hiccups, shouts and brawls… why this? If not that violent and impetuous wine”.

As with the Greeks, the Roman view was far from uniform. Cato the Elder, though a moderate drinker, wrote an influential treatise on agriculture in general, mostly focusing on viticulture; a pursuit he deemed noble and essential.

Even though prominent men, like Julius Caesar, were singled out and lauded for their sobriety; the fact that they were done so tells its own story. Indeed, estimates on an average citizen’s consumption of wine are up around the 100 gallons per year mark.

And Mark Antony wasn’t the only one who unleashed their passions through the drinking cup. Sulla, Cato the Younger and the wanton and embarrassing daughter of the Augustus, Julia, were all renowned lushes.

N.B. Julia was embarrassing because Augustus, most probably in an attempt to distance himself from the behaviour of his nemesis, Antony, implemented a series of morally austere laws which actually bore his daughter’s name!

The emperors Tiberius, Claudius, Vitellius and Commodus were also notorious imbibers.

The prevailing attitude towards alcohol was one that, like today, is hard to understand. Moderate drinking seems to be almost universally accepted and chronic drunkenness frowned upon.

While there was certainly no idea that getting tanked might be an addiction or disease for which one ought to be pitied, those who indulged were not uniformly disgraced; it would have been hard to imagine Mark Antony’s or Alcibiades’ unquestioned virility and brilliance decoupled from their dependence on the bottle.

What is more, as today, drunks and drunkenness made excellent subjects for comic writing (c.f. Petronius’ Satyricon).

Indeed, except for religious prohibitions and increased medical awareness, attitudes towards drinking are one of the least changed of all the varied and subtle differences that distinguish us from our forefathers.

It appears then, that a thin, if slightly wobbly and difficult to focus on, thread connects us to our ancestors by countless centuries and untold, unwarranted guffaws – something certainly worth raising a glass to.

Cheers!

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.