Classical Wisdom Weekly / Wednesday July 17th, 2013

- How did the Greeks enjoy theatrical festivals?

- What role women played on and off the stage,

- Crassus tries to flee from the Parthians, but can he?

——————————

Quotes of the Day:

“This is slavery, not to speak one’s thought.” – Euripides, The Phoenician Women

“Don’t kill the messenger.” – Sophocles, Antigone

“A man, though wise, should never be ashamed of learning more, and must unbend his mind.” – Sophocles, Antigone

——————————

Dear Classical Wisdom Readers,

Your editor is currently on the road. We left the 3,500 year old town of Budva, Montenegro yesterday. Historically known for its ancient and mythical origins by the Phoenician hero, Cadmus, the popular beach resort now allegedly sports the largest discotech in Europe. Your editor wisely decided to not check it out. Instead, we flew to the second largest city in Greece, Thessaloniki. As it was once a co-reigning city of the Eastern Roman Empire (alongside Constantinople), we find Roman, Byzantine and Paleochristian, but not Greek, ruins that remind us of the city’s ancient past. This includes the arch of Roman emperor Galerius, The church of Hagios Demetrios, Roman bath houses and forums….

But it wasn’t always that way… in fact Thessaloniki was founded around 315 BC by the King Cassander of Macedon, who named it after his wife Thessalonike, a half-sister of Alexander the Great. After the kingdom of Macedon fell in 168 BC, Thessaloniki became a free settlement of the Roman Republic headed by the famous Mark Antony in 41 BC.

Eventually the Roman empire also fell, in 476 AD, but the city still stood and became an important centre for the spread of Christianity. You may note that the first written book of the New Testament, transcribed by Paul the Apostle, is none other than the First Epistle to the Thessalonians.

Unfortunately, we don’t have much more time to explore this old city, and will leavetomorrow in search of Alexander the Great’s Macedonian roots.

If you have any suggestions or requests of where your editor should venture on our way down to Athens, please feel free to write us at: [email protected].

In the meantime, immerse yourself in the world of Ancient Greek theatrical festivals… Ben Potter takes a look at the time honoured tradition as well as the controversial role women played at the events. Additionally, we have the next installment of the Battle of Carrhae. Our last article was left with Publius’ head on a spear, which was offered to his father, the wealthiest man in Rome, Crassus. But how will the Romans fare against the Parthians?

Sincerely,

Anya Leonard

Project Director

Classical Wisdom Weekly

——————————

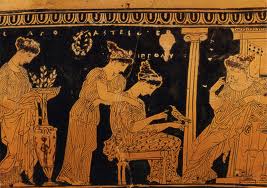

Greek Theatre: It’s a Man’s World?

by Ben Potter

A quick search of our homepage will reveal that a copious amount of ink has already been spilt discussing the life and works of the great practitioners of Athenian theatre: Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes.

However, leaving aside these individuals for the moment, brilliant as they may have been, what of the vehicle of delivery itself? No, not the actors, nor even the venue, but the festivals in which seminal works such as Oedipus Rex, Electra, Ajax, Orestes,Prometheus Bound, The Wasps, The Knights, and Philoctetes were showcased?

The two major Athenian theatrical festivals, The Lenaia and The City Dionysia were held in honour of the god Dionysus. Calling them theatrical, whilst not misleading, isn’t wholly illuminating as they were merely primarily, not exclusively concerned with theatre.

The two major Athenian theatrical festivals, The Lenaia and The City Dionysia were held in honour of the god Dionysus. Calling them theatrical, whilst not misleading, isn’t wholly illuminating as they were merely primarily, not exclusively concerned with theatre.The Lenaia lasted for four days during January/February and, because of the time of year, was almost exclusively attended by Athenian residents, due to little winter shipping in the Mediterranean.

The Lenaia was originally a festival of comedy (although tragedy was introduced in 488 BC), probably because there was more scope for political and social ‘in-jokes’, as the audience would have consisted of few non-citizens.

Alternatively, the City (or Great) Dionysia lasted six days and took place in the spring (March/April). Consequently it could have been attended by citizens from Athenian colonies (in addition to friendly travelers) because shipping would have resumed by this point.

Two things are noteworthy about the City Dionysia. Firstly, it was solely a festival of tragedy until 432BC, and it was the main event, the big deal, the Oscars to the Golden Globes of the Lenaia. Secondly, it seems the Dionysia was ‘more religious’ or, perhaps, more preoccupied with traditional religious practice than the Lenaia.

Supporting evidence comes from Oswyn Murray in his comprehensive Early Greece: ‘the festival involved an annual procession of the ancient statue of Dionysus from Elutherai (a mountain settlement on the northern borders with Boeotia) to Athens’.

Supporting evidence comes from Oswyn Murray in his comprehensive Early Greece: ‘the festival involved an annual procession of the ancient statue of Dionysus from Elutherai (a mountain settlement on the northern borders with Boeotia) to Athens’.This shows us that if one wished to take in a show then, at the very least, one would have to feign interest in a religious procession.

Classics professors looking to justify their tenure have made a lot of the ins and outs of these two festivals. However, something really interesting, and still now ambiguous, is the role women who were allowed or obliged to play in them.

Women would certainly have had a role to play in the holy procession and been given a share of the rare and delicious animal sacrifice. Additionally, women were generally a vitally important part of most Dionysian rituals in their official status as his Maenads/Bacchae (specific female acolytes).

Beyond this, things get a little sketchy, as reliable evidence for Athenian women (their lives being private, domestic and illiterate) is scarce. However, we do have reason to believe women were allowed to attend dramatic festivals even if, like in Shakespearean London, they were not permitted to act in them.

We look to the comic masterpiece of Aristophanes, The Frogs to confirm this: ‘Every decent woman or decent man’s wife was so shocked by plays like Euripides’Bellerophon that she went straight off and took poison’.

There is a school of thought that says women were perhaps allowed to attend tragedies, but not comedies.

The main argument for women being excluded from comic shows is that comedies would have been a ‘bad influence’ on the ‘easily susceptible’ (i.e. women), whilst tragedies had an important moral message to teach. This, however, does not hold up to closer scrutiny. In Aristophanes’ comedies the women behave no worse (and usually better) than the men, whilst in tragedies such as Medea we see a woman kill her babies. Additionally, in Agamemnon we see a woman kill her husband, and in Electra we see a woman kill her mother and display incestuous feelings towards her father.

Thus it’s hard to imagine that the corrupting influence of bawdy jokes and toilet-humour would have been more damaging on the delicate sensibilities of Athenian lady-folk than tales of incest, murder, suicide, treachery and blasphemy.

Furthermore, if women could attend one branch of theatre, but not the other, then we may expect to be told somewhere why this was (or at least have it joked about by the waggish Aristophanes).

So were women supposed to learn important lessons at the theatre?

Most Athenian women (even of the upper classes) would have received little or no formal education whatsoever, so these infrequent visits to the theatre would have been probably the only opportunity for mass enlightenment.

Most Athenian women (even of the upper classes) would have received little or no formal education whatsoever, so these infrequent visits to the theatre would have been probably the only opportunity for mass enlightenment.We can see in plays such as Aristophanes’ Assemblywomen (396 BC) that an attempt is made to communicate ideas women may never have had the liberty to contemplate. The brief plot of this comedy is that the women of Athens obtain power of the city through an elaborate scheme in which they descend on The Assembly dressed in drag.

This play could be Aristophanes’ attempt to champion the rights of Athenian women by implying that not only are they capable of creative/devious thinking, but also that they may be suitable to play a political role.

Likewise in Lysistrata (411 BC), in which the Athenian women go on a sex strike, Aristophanes could be challenging the existing system of the husband being kurios(master) over his wife. Such plot lines may have been seen as subversive, however if they were, would any serious message have had less of an impact when veiled in comedy? Perhaps so.

The argument that Aristophanes had no interest in transmitting a political or social message is groundless. Cambridge professor Paul Cartledge pointed out that the controversial and powerful demagogue ‘Cleon thought Aristophanes was worth taking legal issue with’ and Aristophanes actually rewrote his satirical Clouds to make it more strongly political.

Euripides was another major playwright who conveyed a strong message to his female audience; a very different and possibly more effective message than Aristophanes.

Euripides has been called everything from a misogynist to a feminist and was blatant in his attempts to suggest that ‘clever’ women should not be trusted. Most obviously inMedea (431 BC) where the title character is a woman who has given up her citizenship and then murders her children following her husband’s affair.

This powerful and emotive play could have been Euripides’ attempt to persuade women of Athens to stay loyal to the state, not be overly concerned or jealous about their husband’s extra-marital misdemeanors, and generally to be wary of concerning themselves in ‘male’ matters.

However, it could have been just the opposite. A message to women that they don’t need to put up with this sort of thing and a warning to men that, despite their great power and social status, despite the world being run by them, for them, they could lose everything they cared about in the blink of furious, female eye.

However, moving away from the speculative, we must address the very real possibility that women had little significance at all in the two festivals.

Apart from the actual opening procession itself, women may have had not much to do. Even assuming women were allowed to attend all the theatrical productions, perhaps none of the performances were geared towards them.

In Assemblywomen the underlying message of the play is that the current politicians in Athens were so poor that even a woman would make a better leader! And the fact that rule by women is considered a suitable topic for a comedy indicates that the message of the play is not towards women but a scathing attack on low-caliber politicians.

Likewise in Lysistrata it seems that the theme is more the obtainment of peace than sexual equality.

Euripides’ negative (or at least extreme) portrayal of women could easily be a reminder to Athenian men to keep close watch on their wives and perhaps not allow them too much freedom.

It seems that the main and key advantageous role women had at these festivals was to receive a preciously rare moment of education at the theatre. This, however, was no official or even planned act, but more the accidental vehicle by which individual playwrights could spread their influence further.

The fact that Athenian women would have had so little access to creative thinking and ideas would have meant that, for the individual women, this day would have been of great significance, even if their formal role in the festivals would have been rather limited.

Thus, we cannot really conclude on a truly positive note that theatre was a vehicle of emancipation that changed female Athenian society. What it was, however, was a pinprick of light in a life of repetition and banality, a highpoint of refinement, art, culture and beauty to liberate and elevate a class of society, which had less potential for social progression than the bevy of slaves who kept Athens ticking.

Even if only for a moment.

——————————

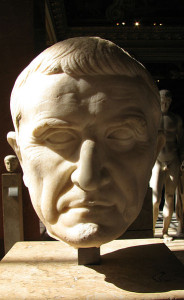

The Battle of Carrhae rages on…

It’s the Romans, headed by Crassus, against the Parthians, led by the tricky general Surena. Every step of the way the Parthians have employed ruses to dissect and destroy the Romans. Crassus’ own son, Publius, was among the deceived, and followed the horse archers away from the main army and into an ambush. We last left the battle with Publius’ head being offered, on a spear, along with a chilling note to his father, Crassus… Read below to see what happens…

Need to catch up?

Read Part I – “Dark Moments in Roman History: The Battle of Carrhae” HERE.

Read Part II – “Battle of Carrhae: Shower of Death” HERE.

Read Part III – “Battle of Carrhae: Heads will Role” HERE.

——————————

Crassus’ Retreat in the Battle of Carrhae

by Cam Rea

As soon as Crassus was done preparing the men for the second wave of battle, the Parthians quickly got to work by enveloping the Romans and showering them with arrows. As the horse archers began to pelt the enemy to death, Surena decided to up the carnage by unleashing the cataphract.

The strategy was simple, with Roman confidence withering away; the cataphract would have a much greater chance in driving the infantry closer together and into each other’s way. With each charge the cataphract was successful in penetrating the Roman lines and quickly breaking from the engagement, which allowed the horse archers to concentrate their arrows on a compacted target. The Romans were losing men quickly during this combat as the arrows constantly rained down and the cataphract kept crushing and driving bodies back. Crassus had no choice but to retreat… but to do so in the daylight was far more risky and the night could not come soon enough.

The strategy was simple, with Roman confidence withering away; the cataphract would have a much greater chance in driving the infantry closer together and into each other’s way. With each charge the cataphract was successful in penetrating the Roman lines and quickly breaking from the engagement, which allowed the horse archers to concentrate their arrows on a compacted target. The Romans were losing men quickly during this combat as the arrows constantly rained down and the cataphract kept crushing and driving bodies back. Crassus had no choice but to retreat… but to do so in the daylight was far more risky and the night could not come soon enough.As the sun set, the Parthians withdrew from battle. The Romans could now try to gather their senses and make plans on what to do next. It was during this time that the Parthians sent a messenger to Crassus. They will give Crassus some space to mourn the loss of his son, but they also advised Crassus that he should go to Orodes, unless he desires to meet his son in the afterlife.

Crassus did neither. Instead, he was found lying down in the dark with his face covered. The remaining Romans were in a similar state of mind. Not a finger was lifted to help the wounded or bury the dead. As Crassus laid in silent anguish, an officer by the name of Octavius tried to motivate Crassus to get up and take charge of situation. Crassus did not budge nor show signs of concern.

Consequently, the Roman officers got together and made the decision to move out. They packed their camp and left, leaving the maimed behind and the dead to be picked clean by the vultures. Absolute panic erupted in the camp as those unable to move shouted to their compatriots for help. Some Roman soldiers did help the wounded but many feared for their lives and ignored the pleas. As the Roman army retreated they continuously altered their course, likely zigzagging at times to throw off the Parthians if they intended to attack during the night march.

The journey was anything but fluid. It was a slow, cumbersome march, as those who had been maimed handicapped the Romans’ move to reach temporary safety. However, some men, like Ignatius and his 300 cavalry, quickly moved ahead of the main body and in doing so reached the city of Carrhae around midnight. Once Ignatius was outside the walls he yelled to the sentinels in Latin. He informed them to tell their commander Coponius that there had been a “great battle between Crassus and the Parthians.”

Afterwards, Ignatius moved to the safety of Zeugma, leaving the main body behind and acquiring a bad name for deserting Crassus. Consequently, Coponius was suspicious of the news. Ignatius never gave his name or any details as to what had happen. Coponius ordered that his men immediately arm themselves and soon learned that Crassus was on his way. Coponius quickly went out to relieve Crassus and escort the Roman army into the city.

Afterwards, Ignatius moved to the safety of Zeugma, leaving the main body behind and acquiring a bad name for deserting Crassus. Consequently, Coponius was suspicious of the news. Ignatius never gave his name or any details as to what had happen. Coponius ordered that his men immediately arm themselves and soon learned that Crassus was on his way. Coponius quickly went out to relieve Crassus and escort the Roman army into the city.The Parthians were not ignorant of the situation. They knew that the Romans had fled. Once dawn broke, the Parthians mustered their forces and moved out to the battle site and saw only the dead and maimed. Those who were still partially alive, 4000 in total, were killed.

Afterwards, the Parthians pushed on searching for stragglers and slaughtered them. Only twenty men survived and were allowed to leave for Carrhae due to their courage.

Then Surena received a report that Crassus had bypassed Carrhae and escaped with the main body. All that was left in Carrhae was just some stray soldiers. Surena had one of two options, either run around the desert looking for Crassus, wasting time and energy, or send one of his own men who could speak Latin to Carrhae and ask questions. Surena decided on the latter, and ordered an interpreter to probe Carrhae.

Once at the walls, Surena’s man relayed the message that Surena wished to have a conference with either Crassus or Cassius. If they accept, they would be allowed to depart safely after they had negotiated the terms with the king and left Mesopotamia indefinitely. Crassus accepted the invitation and Cassius informed the messenger that the “time and place be fixed for a conference between Surena and Crassus.” Parthian intelligence just paid off. Surena was on his way to Carrhae.

Crassus had hoped that what was to come was real, as he and his men were desperate to make their way home. However, it was a trick all along. There was no truce, at least not how it was initially perceived.

The next day, early in the morning, Surena gave the order to move out and head towards Carrhae. The sentinels on the walls notified Crassus and Cassius that the Parthians were near. Cautious joy was likely the response among the men, but once Surena was outside the city walls, there was no peace offer.

Instead, the Parthians began to hurl insults and demanded that if the Romans want peace, then they must hand over Crassus and Cassius in chains. The Romans were stunned by this request and grew angry… the whole proposal of peace talks beforehand was just a facade. Crassus was in a dire situation. Carrhae could not provide the supplies needed and no Roman troops were available in Syria to come to their aid. Crassus then made the decision that they will move out during the night once again, since the Parthians apparently didn’t fight so well after sunset.

Crassus decided that they would march to the town of Sinnaca, located in Armenia. Reaching the place would be no problem under the cover of darkness… so long as your guide is not a double agent…

Tune in next week for the final installment of the Battle of Carrhae!

——————————

Classical Wisdom Weekly is only 9 months old and already we have 1000s of keen and vocal followers (you know who you are!) We’d love to hear your feedback on our project and how it is going. If you would like to send us a few thoughts, please address them to your managing editor at [email protected].