Written by Lydia Serrant, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Since ancient times, the Greeks have respected their gods and goddesses. Political events often lead to the building of divine temples and structures—and sometimes their destruction. It wasn’t until the Athenian victory over Persia in 490 BC that Athens was appointed the Defender of Greece, and smaller city-states began paying tribute to the city for their protection.

Wealth poured into the city, marking the beginning of the Golden Age. During this time, many temples were built. Huge, illustrious monuments dedicated to the gods were also erected to demonstrate Athens’ power and wealth.

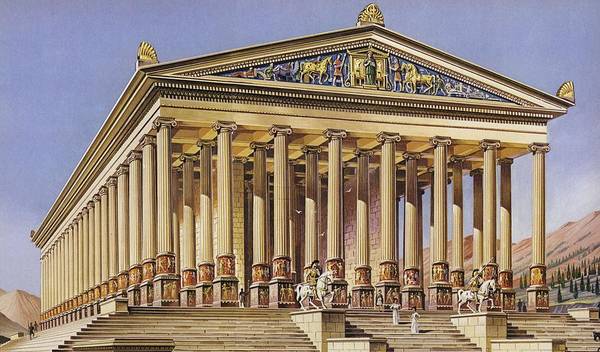

This period saw the development of the three Classical Greek architectural styles, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian. They are distinguished by distinct styles of columns and entablature (structures that columns support, such as the frieze, cornice, architrave, etc) and appear mainly in marble, which replaced earlier wooden structures.

Early eighth-century temples were constructed with wood and thatched roofs, but during the sixth and seventh centuries, the Greeks began to utilize more lasting materials. Some buildings used a mixture of marble and wood, while other more important buildings like temples used limestone with a marble coating or marble dust stucco.

The temples and buildings in ancient Greece were more than just marble and mortar, however. They held important political and cultural significance. Just like the Egyptians, the Greeks used their mastery of masonry to preserve their history, religion, and culture for contemporary and future generations to admire, study, and enjoy.

The Parthenon and Acropolis

The Parthenon of Athens is perhaps the most iconic example of Doric architecture. Built between 447 and 432 BC during the Greek Golden Age, the Parthenon (which means the Apartment of the Virgin) was built in honor of the goddess Athena. The project was supervised by the sculptor Phidias and featured eight Doric columns on the narrow facades and seventeen columns along the sides. The friezes and metopes depict over 360 humans in famous battle scenes as well as gods and animals.

The Acropolis, in which the Parthenon stands, was first constructed as a military base due to its advantageous position atop the Hill of the Muses. This strategic position allowed defenders to spot any approaching enemy for miles. There is evidence that the area was inhabited as far back as the fourth millennium BC.

The Acropolis is a reflection of the wealth and power of Athens, and as the city grew in strength, so did the Acropolis. Architects and master builders added several magnificent structures to the Hilltop: the Erechtheion, Propylaea, and the Temple of Athena Nike. The Acropolis hosted many festivals, the most important being the Panathenaea, a grand festival of sacrifice in the Cult of Athena.

The Golden Statue of Athena

Inside the Parthenon, there was statue of Athena made out of solid gold and ivory. Such grandiose materials were reserved for only the most highly-regarded gods and goddesses. Sculpted by Phidas in 447 BC, the statue stood at approximately 37ft and was the focal point of the Parthenon. It showed the goddess holding the goddess Victory in her right hand. The statue of Athena was continuously assembled and dissembled in parts and weighed, to ensure that no one was slowly chipping away at the costly statue. If any of the weights came up short, it was said that the citizens of Athens would suffer the wrath of Athena.

However, over time, such superstitions were ignored by the Athenians. The gold was stripped away in 296 BC by the tyrant Lachares to pay his troops, and further damaged by fire in 165 BC. It was modestly repaired in bronze and retained only some of the original material. It is said that this replica was finally removed from the Parthenon by the Christians and displayed in the Forum of Constantine in Byzantium. Thereafter, all traces of the statue were lost. It is believed that the statue was destroyed in 1204 during the sack of Constantinople during the Crusades.

Stoa of Attalos, Agora

As the Etruscans were weakening against a fledgling Roman Empire that would one day rule Athens, the Athenians continued to revel in their power. This sense of invincibility emanated from the Agora, the busy and bustling center of the Athens. Here stood the marvelous Stoa of Attalos, constructed as a gift from the Anatolian leader Attalos II of Pergamon in gratitude for the education he received there.

The Stoa of Attalos was larger and more decadent than the earlier buildings installed at the Agora. Since 1931, more than 100 ancient buildings and over 2,000 antiquities have been uncovered in the center of the modern city, but none compared to the scale and magnitude of the Stoa. Built in Pentelic marble and limestone, the structure spanned 115 by 20 meters and required skillful work to complete.

At the time of its construction, most Athenians believed in their educated democratic government, despite issues like slavery and corruption. It was in the Agora that the first jury system was conceived, another features of democracy we recognize to this day. However, not even systems of law were free from Athenian superstition; many Greeks believed that murderers polluted the sacred rooms of justice, so murder trials were held outside.

Destroyed by Germanic tribes in 267, the remains of the Stoa were used as a defensive military wall until its 1952- 1956 reconstruction by the American School of Classical Studies. This is now a museum dedicated to the ancient Agora.

Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Acropolis

Set afoot the southwest slope of the Acropolis is the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, built in the memory of his wife Aspasia Annia Regilla. Although principally an outdoor theatre, the regional structure featured an expensive Lebanese cedar roof and a three-story front wall.

Ancient inscriptions record theatrical contests held there in 503 BC: in effect, this was the ancient Greek equivalent of the Golden Globes or the Oscars. At the Odean, physical and artistic expression was expressed publicly to wide acclaim. Today the structure has been rebuilt in Pentelic marble and is a modern venue for a variety of Greek and international musical and theatrical performances.

Temple of Artemis, Corfu

Known as one of the greatest masterpieces of its time, the temple of Artemis was built in 580 BC in the ancient city of Korkyra on Corfu, now modern-day Garitsa.

Constructed in the Doric style, the temple of Artemis was the largest of its time. Decorated with mythical figures and depictions of Achilles and Memnon, it is believed that the temple of Artemis influenced the design of Italy’s St. Omobono church, a testament to the legacy of Greek architecture.

Acropolis of Sparta

When we think of the Acropolis, we are reminded of the magnificence of Athens, but Sparta – ever the rival – also built an impressive Acropolis during its brief period of dominance.

Sparta reached the height of its power in 404 BC after defeating Athens in the Second Peloponnesian War. During this time, the Spartans built an impressive Acropolis. Today, only a few ruins are left. Handwritten accounts from non-Spartans discovered a few kilometers away from the ancient city help us imagine this once-glorious structure.

At least three buildings were located within the Spartan Acropolis. The one that survived the best is the Temple of Athena Chalkoikos, which was designed by the architect Vathyklis of Magnesia. It was said to have an interior adorned entirely in copper (chalkikos means copper).

The Acropolis also housed a theatre on its south side. The remaining wall has preserved inscriptions and sculptures of Spartan rulers during the Roman period. There was no permanent stage at the Spartan theatre. Instead, the Spartans used wooden pallets to easily move stages in and out of place during different performances.

This feature, along with the existence of many other structures of unknown significance found at the site, demonstrates that Sparta was not only a military state but also one in which ingenuity, art, culture, and poetry prospered. In fact, more poetry belonging to Sparta than Athens has been discovered.

The Decline of Greece and Athenian Supremacy

When Athens was conquered by Spartans and the Athenian spirit waned, several political and environmental upheavals ensured that Athens’ Golden Age was well and truly over.

First, a devastating plague swept across Athens taking thousands of lives. According to Thucydides, people despaired, disrespecting the laws and the temples because they felt they were already living with death. As plagues, wars, and religious doubt mounted, Athens’ glorious monuments were at risk. The city of Athens was no longer in a position to protect anyone, not even herself.

The Greek city-states received a crushing blow when the Romans invaded and plundered many towns. They were, however, extremely respectful of Greek education and culture and willing to preserve certain aspects of Greek civilization. It is thanks to Roman admiration for Greek society that many artifacts and buildings survived.

During the Turkish invasion of Greece in 1456, the Turks installed and a mosque inside the Parthenon and the Turkish military kept their war machines and ammunition stored there. Later, in 1687, the Venetians bombed the Parthenon,setting off all the Turkish ammunition. With this act, the Acropolis, the epicenter of Greek influence and thought, was finally and destroyed. No one looked to the Parthenon as a center of culture and history anymore. Instead, the Athenians hauled broken marble away to build homes and other public houses. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the Greek government began the painstakingly intricate task of restoring the entire Acropolis, work that continues on to this day.

References:

Meiggs, R. (1963). The Political Implications of the Parthenon. Greece & Rome, 10, 36-45. Retrieved April 9, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/826894

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.