Written by Michael Fontaine, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Whew! Got all that? (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, please first read Part 1.)

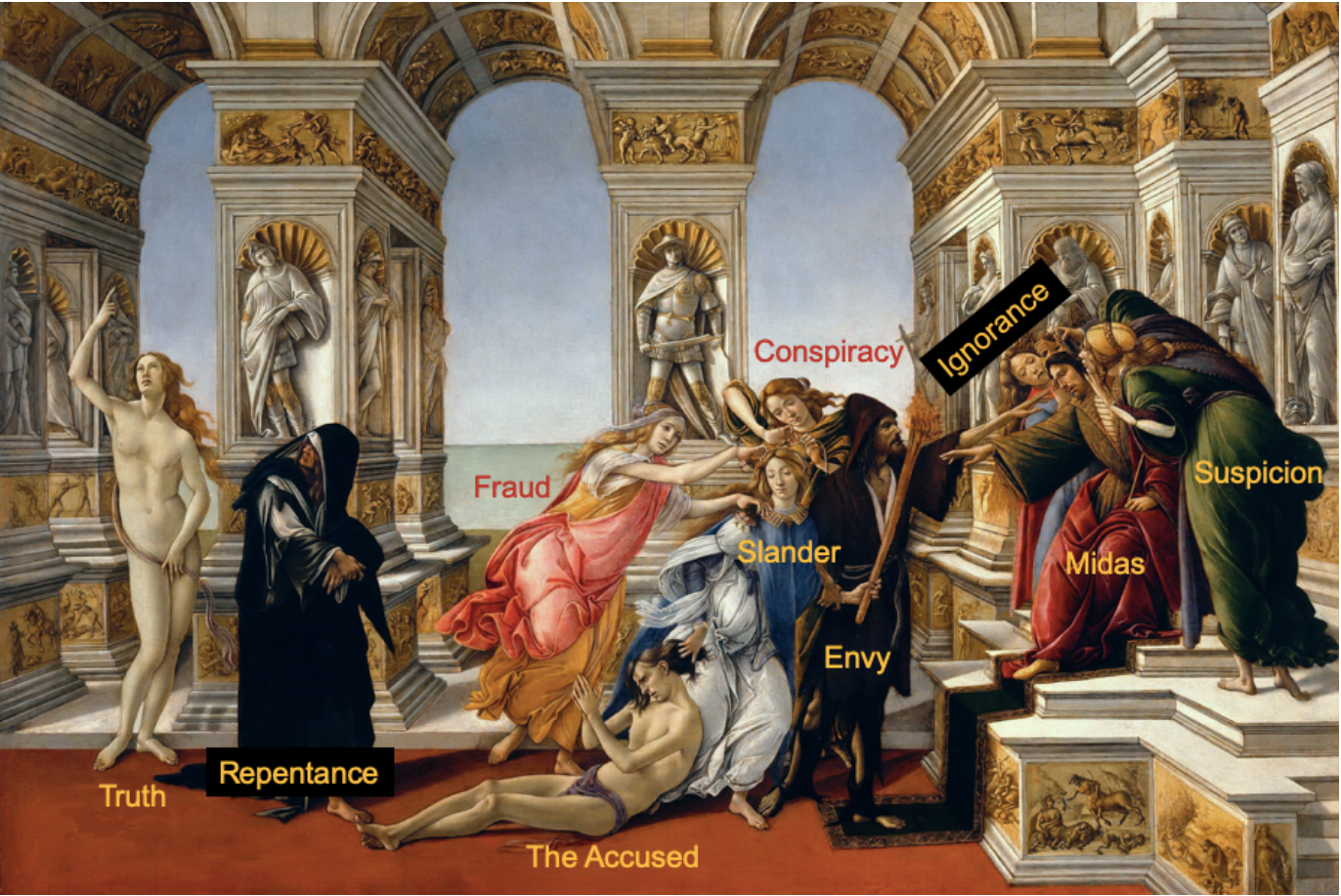

Now watch this, because it’s relevant to Obsopoeus. Lucian:

(1) applies

(2) the allegorical women he’s “described” to

(3) the peer pressure that thrives among courtiers in the Hellenistic world—including

(4) the pressure to drink alcohol.

Take a look:

“At Alexander [the Great]’s court there was no more fatal imputation than that of refusing worship and adoration to Hephaestion. Alexander had been so fond of him that to appoint him a God after his death was, for such a worker of marvels, nothing out of the way. The various cities at once built temples to him, holy ground was consecrated, altars, offerings and festivals instituted to this new divinity; if a man would be believed, he must swear by Hephaestion. For smiling at these proceedings, or showing the slightest lack of reverence, the penalty was death.”

Peer pressure and compulsory drinking thrived at court, too:

“Demetrius the Platonic was reported to Ptolemy Dionysus for a water drinker…. He was summoned next morning, and had to drink in public.”

These are the connections Obsopoeus saw, and the potential he developed, in creating his own glorious “lost allegorical painting by Apelles” of the perils that lie within The Garden of Drunkenness.

It’s important to realize that Renaissance Germany (“The Holy Roman Empire”) was a lot like the Hellenistic world. It was a patchwork of petty kingdoms and principalities, each with its own court—and each one crammed with courtiers, anxious and insecure about their position. Obsopoeus noticed the same pressures to conform erupting in his own day that Lucian had seen in his.

As he writes in The Art of Drinking,

“No other vice [than drinking] has so gotten a grip on the courts of the mighty… At times the courtly life is one of perpetual drunkenness, on par with the drunkenness that captures citadels, and at times a treasurer, knight, mayor, muleteer, scribe, or cook who shows up for work sober is an unwelcome sight to that bloated court.”

And so on. (He goes on about this at great length.)

Seeing that essay so dramatically illustrated right down the street just a few years prior, by no less than Dürer (pictured above), would have made it famous, and Obsopoeus’ allusions unmistakable, to all the literate public. Nuremberg was the center of German Renaissance culture at the time, and everyone knew it.

What’s more, Nuremberg is the very city where Obsopoeus failed to get a job a decade before he wrote The Art of Drinking—failed, that is, because of his reputation for drinking! As I wrote in The Pig War:

“Vincent Obsopoeus (?-1539) was a gifted translator, a superb Latin poet, a minor figure in the Reformation, and he was, by all accounts, an obnoxious guy. He delighted in twitting others for their failings, however minor. It is only too believable that he could have written The Pig War. Five years earlier [in 1525], he had angrily accused [Philip] Melanchthon of passing him over while recommending people for jobs at the new Gymnasium in Nuremberg; Melanchthon had (said Obsopoeus) ridiculed him on various grounds, not least his drinking.”

So, that would all be cool all by itself. But now, get ready for something even cooler: the master stratagem, the immortal troll .

The Immortal Troll

How do you slander someone? Well, says Lucian,

“The usual method is to seize upon real characteristics of a victim, and only paint these in darker colors, which allows verisimilitude. A man is a doctor; they make him out a poisoner; wealth figures as tyranny; the tyrant’s ready tool is a ready traitor too.”

How do you slander someone who enjoys wine? The question answers itself – and it shows how Obsopoeus played chess six moves ahead of his enemies.

Here’s how.

I didn’t have room to include Obsopoeus’ preface in my translation of The Art of Drinking, but I published a translation online a few months ago (here).

In it we learn that Obsopoeus – a gifted translator – had recently lost out on some commissions to translate classical literature, apparently on the grounds that he wasn’t a serious enough person to handle great “works of art.” And that’s why, he says, he turned his attention to the one “art” that everyone thought he was worthy of: the art of drinking.

Dripping with venom, he declares,

“My other reason for [writing The Art of Drinking] is the false opinion some people have of me, and the smears that certain trash talkers have put out there. When they go accusing me to one and all of being a ‘world-champion wine drinker’ (which isn’t true, and nothing I’ve ever done to them ever provoked them to say that, other than their being unable to live without blackening someone else’s good name); — those stupid idiots don’t understand that they’re actually ‘insulting’ me in the most honorable way possible….You see, I do like wine more than water, but I’ve always controlled my enjoyment of it with such moderation that I’ve made sure that no one’s ever gotten misled or hurt by my drinking.Meanwhile, those sobriety-worshippers who are slandering me—who go around signaling their virtue in public while binging in private—they’ll surely spell the doom of no few people with their destructive teaching, contaminated as they are by far more disgraceful sins and behavior.”

I see what you did there, Obsopoeus. In addition to its inherent wisdom, all of book two is an ironic immortalization of those sobriety-worshippers who slandered you. You used Lucian’s essay to box them in – and anyone who ever went down the street to Nuremberg’s famous town hall to see Dürer’s fresco would have known it.

Well played, sir.

A Coda: Friedrich Spee and the Witch Trials of Franconia

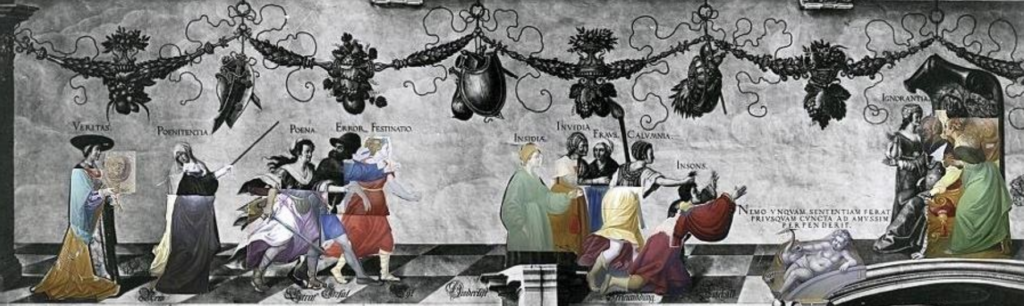

There’s a sobering coda to add about Lucian’s warning—or rather, the failure to heed it. When Dürer frescoed the Nuremberg town hall, he added a motto in Latin: Nemo unquam sententiam ferat priusquam cuncta ad amussim perpenderit.

“No one should ever convict without considering everything scrupulously.”

He put the same idea in German just off to the right:

Ein Richter soll kein Urthel geben.

Er soll die Sach erforschen eben.

The point was hard to miss: Don’t just listen to an accusation. Facts and motives matter, too. You must do your all to search them out when someone tells you something awful.

Alas, a century after Dürer laid his brush down, a horrific spate of witch trials broke out around Nuremberg. Hundreds were falsely accused and burned at the stake. Overzealous prosecutors breached their procedures and abused their power to secure convictions, accepting all kinds of absurd slanders as “evidence.”

A whistleblower named Friedrich Spee (1591-1635), a confessor priest, published an important book itself titled Slander, A Warning (for that is the meaning of Cautio Criminalis) in an effort to deter prosecutors and halt the madness. In the moment, it achieved little. Later, when asked why he’d gone prematurely grey, Spee replied with grim humor:

“The witches turned my hair white”

—not by magic, but—

“…out of the grief I feel for the many innocent witches I’ve accompanied to the stake.”

It all goes to show that the earth spins, but little changes. Looking back now, Lucian was right all along.

One comment

hi

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.