By Mary E. Naples, M.A.

Did God have a wife? Was a female deity revered alongside the monotheistic Hebrew god, the one most of us in the West know from the Old Testament? It may sound like an outlandish notion, but perhaps there was a lost Hebrew Goddess that, at times, reigned supreme in the ancient Mediterranean cultures.

Asherah, called Athirat in Ugarit, figures prominently as the wife of El, the supreme god, in cuneiform alphabetic texts, dating back to the fourteenth century BCE. Before Abraham (ca 2200-1700 BCE) migrated to what would become known as Israel, Asherah was revered as Athirat, Earth Mother and Fertility Goddess. Upon entering the region, the ancient Israelites adopted her and gave her the Hebrew equivalent name of Asherah. The Ugarit excavation, a second millennium “Canaanite” port city (in today’s northern Syria), put Asherah the goddess, on the map again after having lost her place for thousands of years.

Of course the presence of a Hebrew goddess immediately begs the question: how monotheistic were the pre-exilic Israelites and Judeans? Certainly, the very notion of polytheism is inherent in the quest for Asherah.

Additionally, the many artifacts representing Asherah, and her cult from the region, belies the biblical prohibition against the creation of idols.

At this juncture it is important to make a distinction between the book religion of the ruling classes in the metropolis and folk or popular religion as it was practiced in rural communities, for which most Israelites were a part.

Moreover, it should be remembered that in rural communities of the ancient world, literacy was close to non-existent. Indeed, even rudimentary writing did not become widespread until the eighth century BCE, at which time some were able to write their names, numbers and a few commodities for trade… This was certainly a long way from being able to read or write the literary achievement that we find in the Hebrew Bible!

Thus, the book religion practiced in the cities would likely have had little meaning in the lives of those inhabiting the outlying areas. Instead, the rural communities had their own religious beliefs and practiced their faith locally, even at home using statuary and other artifacts. It was very likely that some form of folk religion had been passed down through the generations, making homespun beliefs an integral part of their everyday lives. Indeed, one scholar defined folk religion as everything that those who wrote the Bible condemned.

By way of contrast, an affinity between the intellectual community and the aristocracy produced a masterful text, which was written entirely from the perspective of the upper or ruling classes.

So if the Bible was authored by and large for the ruling class, then how do we know the way common people worshipped? As mentioned above, there are artifacts from the region to help piece the puzzle into place, but it is also ironically in the Bible itself that we can also find many of the rituals practiced by the rural communities. Indeed, Asherah is mentioned in the early Hebrew Bible some forty separate times, although most often as an object of derision.

For the most part, the biblical writers were unhappy that Asherah, or the “Queen of Heaven”, shared the same platform with their male deity, Yahweh, and repeatedly tried to dissuade their union.

Forasmuch as the ruling elite tried to inhibit Asherah and Yahweh’s “marriage,” their union appears solidified in an ancient blessing seen with some regularity at a number of archeological sites in the region. This is particularly apparent in Kuntillet Ajrud, a 9th-8th century BCE Israelite caravanserai with an attached shrine, which was excavated in 1975-76 near the river of Egypt in northeast Sinai (by Judah’s south border).

The text and drawing of the two deities found there sparked a lively debate within the academic community. The inscription reads: “I have blessed you by Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah.” The same text was found a number of times in other locations, such as Samaria, Jerusalem and Teman, where there were known sanctuaries to Yahweh.

More evidence is found in Khirbet el-Qom, an ancient burial site dated to ca 750 BCE, excavated in 1968. The following inscription was found on the tombstone of a wealthy man: “Blessed by Uriah by Yahweh, Yea from his enemies by his Asherah he has saved him, By Onah, By his Asherah and by his Asherah.”

Indeed, the phrase “Yahweh….and his Asherah” must have been a fairly common expression in the region, as sixty miles separates Khirbet el-Qom from Kuntillet Ajrud, not an easy jaunt considering the limited transportation options available at the time.

Moreover, the notable phrase “Yahweh and his Asherah” is in an obscure blessing in the Hebrew Bible itself. The cryptic blessing is in Deuteronomy 33.2-3, in an earlier rendition when Asherah’s influence had not yet been fully subordinated.

The full hymn reads:

“YHWH came from Sinai and shone forth from his own Seir, He showed himself from Mount Paran. Yes he came among the myriads of Qudhsu, at his right hand his own Asherah, Indeed, he loves the clans and all his holy ones on his left.”

However, as the book religion solidified, Asherah became increasingly marginalized in the scriptures… to the point of being reduced to her cult object—the stylized tree or wooden pole which became known as asherah or asherim. Trees were revered as symbols of life and nourishment in arid regions, and so became associated with Asherah and her cult.

Interestingly, many scholars believe that Asherah’s tree functioned in the Garden of Eden parable. Because Asherah’s name was increasingly tied to Yahweh’s in the folk religion of the area, the patriarchal elite may have found it necessary to propagandize against goddess worship by integrating the story of the fall of mankind to the tree which was clearly associated with Asherah.

Asherah’s influence may not have been immense, or even positive, in the official or book religion, but her presence clearly loomed large in the rural communities.

Although we have no text or sacred scriptures from the folk religion of this considerable group of people, we do have much in the way of figurines from the region. To be sure, aniconism was, and still is, inherent in the Hebrew Bible, but ample archaeological evidence suggests that those who lived outside the metropolis—and indeed sometimes right inside it—idolized statuary and cult objects as part of their popular or folk religion.

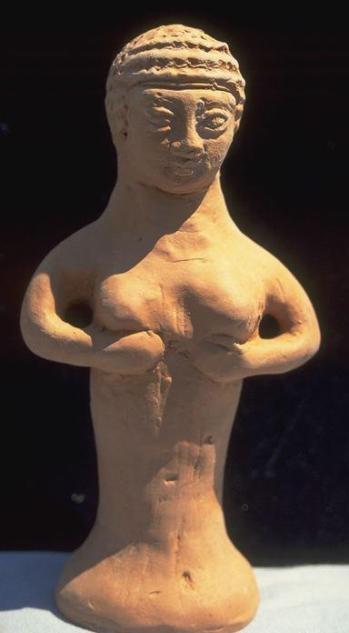

Anthropomorphically, Asherah is represented many times in various forms scattered throughout the region; the most prolific of these is the pillar figurines. These figurines first started appearing in the late tenth to ninth century BCE and had become common from the eight through seventh centuries. The term “Images of Asherah” is used often in the Hebrew Bible, and it is believed that the pillar figurines are what the writers of the bible had in mind.

But what were these figurines meant to convey? Symbolizing the nurturing aspect of the mother goddess, the breasts are exaggerated with the hands more or less supporting them. The pillar figurines were predominantly found in private houses, suggesting their domesticity, and many scholars contend that the figurines represented fertility to women in a region beset by hardship and drought. Sadly lactation and fertility concerns are indicative of some type of famine for which the region was prone. Considering survival was the ultimate burden for the average Israelite/Judean, apprehension about fertility in general was likely widespread.

Was their concern for fecundity what attracted the rural Israelites and Judeans to the goddess Asherah? Reasonably, in a land prone to famine and drought, Asherah may have been linked to the almighty Yahweh because of her association with abundance.

Fascinating as it is, examining a topic that dates back three millennia has its distinct disadvantages. While there are voluminous artifacts and articles associated with Asherah from the region, there are still a number of pieces missing in the puzzle. This, of course, doesn’t prohibit us from attempting to bring the discussion into greater focus, with the distinct hope for further scrutiny and more scholarship to come.

6 comments

I have a news article somewhere that is about a song sung in the synagogue-Come Oh Sabbath Queen. Gonna dig that out and do more research.

Fascinating article, thank you! It is interesting to think about the fact that what is usually passed down is derived from the ruling/powerful of the period and the average person’s experience can become lost. I had not thought about that possibility to this extent where the bible is concerned.

Is there an ancient prayer of The Mother interceding on behalf of her children?

Good read. More articles needed on this subject though

For a closer look at the etymology of the name Asherah, see http://www.abarim-publications.com/Meaning/Asherah.html

Myths and history is very exciting and interesting! I just recently wrote an essay on this topic. This goddess played a significant role in the religion of the ancient Israelites. All the same, it is very cool that in our time we can freely find information about time, myths and legends of those years. And I really like that here I can re-read different myths. Every time I discover something new for myself. I work in the field of writing and, like no one else, I know what an important role word and information play in our life. I work with different sources of information every day and am glad that I often stumble upon something worthwhile. There are a lot of things on the Internet now, and you never know which information is verified and which is not. Therefore, it is very pleasant to stumble upon an interesting forum or site, from which you can glean a lot of useful information. Especially when it comes to history.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.