Category Archives: Sculpture

[post_grid id="10055"]It easily falls into the ‘conspiracy’ category – but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a fun story to tell.

We are all taught that empires rise and fall and that every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end. Ancient Greece and Ancient Egypt were no exception. The year was 1336 BC and the Egyptian Pharaoh, Akhenaten, had just died.

Akhenaten was a strange Pharaoh who shook many of the essential foundations of Ancient Egyptian culture. For one thing, Akhenaten was a monotheist. He only believed in Aten, a Ra-like sun God, a fact that drives some scholars to debate whether he is a founding father of judaism.

Akhenaten was also a romantic, conferring unusual, elevated status to his wife, the famed beauty Nefertiti. He also may have had a strange syndrome or disability which he passed on to his children… something that may have resulted in the early death of his son, Tutankhamun or King Tut.

One the strangest things about Akhenaten though, was that he changed the way art was done in those ancient days. He shunned the rigid rules that maintained 3000 years of artistic stability. Depictions became more naturalistic, especially of plants, animals and commoners. They showed a sense of movement and action.

The royals too were depicted differently. Instead of showing the Pharaoh as god-like, immobile and eternal, the artists began producing tender images of him. He is drawn playing with his daughters beneath the rays of the Aten, while showing his wife affection. The lines surrounding the king are soft and curved. The hard straight features of the previous pharaohs are banished.

But then Akhenaten, the man who is considered “the first individual in history”, died.

Change at first was gradual, but eventually all the reformations faded away and returned to the previous, traditional way of doing things. The time referred to as the ‘Amarna period’ came to an end.

But what happened to all those artists who had just tasted creative freedom? The return to regulation meant the end of artistic liberalism. Did they stay in Egypt after the reversion to the mean? Or did they, perhaps, make their way up north, across the mediterranean?

Around this time, we start to see, for instance, the emergence of Etruscan hieroglyphics, in the land of the Minoans, a pre-Greek civilization.

Eventually, around 750 BC, we come to ‘Archaic’ Early Greek Art.

This time period is characterized by statues that are free standing, frontal and solid. They wear the strange, so-called archaic smile. One foot is placed forward, the fists are clenched. There are three types of figures, the standing nude youth (kouros), the standing draped girl (kore), and the seated woman. All of the different types of sculptures emphasize and generalize the essential features of the human figure.

Now these Greek statues look a lot like the Ancient Egyptian statues.

Of course this story of runaway sculptors, bringing an artistic renaissance and revolution to Ancient Greece, has a lot of holes. The time periods, for instance, are vastly contradictory. It is difficult to imagine keeping this new artistic approach alive for 500 years. The Ancient Greek Kouros also look more like the traditional Ancient Egyptian art, rather than the unique Akhenaten style.

So why did Ancient Egyptian-like statues start emerging in Ancient Greece? Could this just be a coincidence?

We, unfortunately, do not know. They are many other potential explanations, such as the Achaemenid Persian Empire, which was founded in the 6th century BC by Cyrus the Great. This huge empire, which encompassed approximately 8 million km and spanned three continents, would have brought Egypt and northern Greece, Macedonia, under the same umbrella.

The Achaemenid Persian empire also instituted infrastructures, such as road networks, a postal system, and an official language throughout its territories. It even had a bureaucratic administration which was centralized under the Emperor, as well as a large, professional army and civil services.

Maybe the famous Egyptian memorials made their way on these new found roads to Greece’s fledging shores. It is, after all, in this time period when the first Archaic sculptures start to appear.

Or maybe not. History is not an exact science. Dots that seem important might only stick out with hindsight, and connections between them weakened by improbabilities. All we do know, is that Early Greek art starts getting even more interesting from here on out.

—

“Walk Like an Egyptian: Early Greek Art” was written by Anya Leonard

High Classical Greek Art: Political Patrons

Few things impact a budding art scene like an empirical power showing off. The ruling class often invest heavily in propaganda and self grandeur, paid into the hands of the artistically gifted. They might even commission a few temples, as thanks to the gods for their new found positions. The artists, as long as they celebrate approved figures, are rewarded with extravagant commissions. Their patrons, in return, shower their favorite sculptors and painters with prestige and honor.

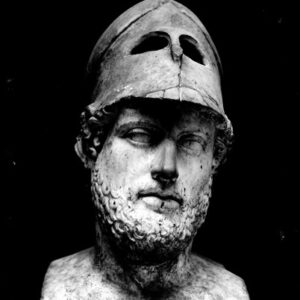

Pericles, the Athenian Statesman, and Alexander the Great, the king of Macedon, were no exception. In fact, the Golden Age of Athenian art – the high Classical greek art period – is broadly defined by these exceptional gentlemen, book holders for fabricated historical boundaries.

Pericles, the Athenian Statesman, and Alexander the Great, the king of Macedon, were no exception. In fact, the Golden Age of Athenian art – the high Classical greek art period – is broadly defined by these exceptional gentlemen, book holders for fabricated historical boundaries.Apparently it all started in 479 B.C. when Athens beat the Persians and founded a confederacy of allies to ensure the freedom of the Greek cities in the Aegean islands. Participants supplied either ships or funds in order to secure protection. This so-called “Delian League”, however, didn’t last long.

Athens wanted an empire, and that’s exactly what it got. First it moved the treasury closer to home – to the imperial city of Athens itself. Then the city-state put forth the Coinage Degree, which imposed Athenian silver coinage, weights and measures on all of the allies. Any left overs from the mint went straight to Athens, and any other use was punished by death.

Now the ordinary Greek members of the Delian league were, in fact, Athenian subjects.

This is where the man who was “surrounded by glory” comes into play. Pericles, who lived from ca. 461–429 B.C., was one of the masterminds behind Athens assuming full control over the league and a famous proponent for Athenian democracy. He then orchestrated one of the greatest human embezzlements of all time. He used the league’s treasury to build some of the most amazing artistic creations of the ancient world. He launched Greek Art into the “High Classical Greek Art”.

This is where the man who was “surrounded by glory” comes into play. Pericles, who lived from ca. 461–429 B.C., was one of the masterminds behind Athens assuming full control over the league and a famous proponent for Athenian democracy. He then orchestrated one of the greatest human embezzlements of all time. He used the league’s treasury to build some of the most amazing artistic creations of the ancient world. He launched Greek Art into the “High Classical Greek Art”.Pericles transformed the Acropolis (including the Parthenon) into a lasting monument of Athens’ political and cultural power. He worked tirelessly, with the likes of the Greek sculptor Phidias, to promote Athens as the artistic center of the Ancient World.

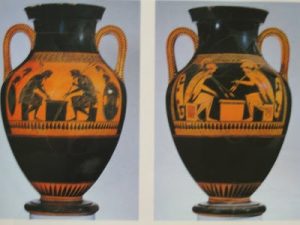

This catalyst propelled Athens further, innovating art on every level, from theatrical works to sculpture to vases. In regards to the last item, a major development occurred in this time period. The red-figure technique superseded the previously traditional black-figure technique. This change may not, at first, seem monumental, but it allowed a greater ability to portray the human body, clothed or naked, at rest or in motion.

Meanwhile, the solid, archaic figures of early Greek sculpture transitioned into more naturalistic statues, revealing movement, grace and the female form. The nude Aphrodite of Knidos, by the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles, was one of the first to break the convention of hiding female figures behind heavily draped attire. In addition to realistic bodies, statues began to depict real people. Democracy trickled down from politics to art.

Among these changing stylistic innovations, developed the art of studying art. For the first time, artistic schools were established, such as the school at Sicyon in the Peloponnese. There students learned the cumulative knowledge of art, the foundation of art history.

It would seem as if the creative boom of the Golden Age would never end. The artistic funds of Athens, however, eventually dwindled along with Athens’ defeat in the second Peloponnesian war.

Fortunately for art, another champion came forward, along with grand commissions and an immense bank account. Alexander the Great, known for his ruthless wars and expanding empire, became a patron of the arts as never before seen… loot from plundered lands will do that. Man is seldom shy of spending other people’s money and Alexander was no different.

It is here that the artificial boundaries of history are vaguely drawn. Alexander the Great, founding great cultural cities around his empire, brought together artistic ideals which had previously never been in contact. Styles and techniques drastically changed throughout the empire’s reach. Was this the peak of Classical art or the beginning of a new age of Art? No one knows precisely when the one period ends nor when the next begins… What follows though, is the final stage of Ancient Greek art… the Hellenistic Period.

—

“High Classical Greek Art: Political Patrons” was written by Anya Leonard

Hellenistic Greek Art

It is easy to have an ‘ideal’ when it is unchallenged. “This king is best”. How readily this bold statement rolls off the tongue, when there is no other king of which to speak. Likewise the phrase, “This God (or Gods) is right” offers no resistance if one’s own knowledge of divinities is severely limited. Similarly, “This is the perfection of beauty” can hold only sway in a small or isolated society.

It is often diversity, then, that invites people to examine their own unquestioned convictions in governance, religion or art. The complementary act of decentralisation, takes these norms and expectations away from one ruling group and puts independent thought and creation into a multitude of hands. There are now many competing ideas and concepts.

It is this diversity that characterizes the era of Hellenistic Greek art, the period of eclecticism.

This multeity was born out of the expansion of Alexander the Great’s empire, though its historical barriers aren’t clearly defined. The King of Macedonia brought extreme and remote regions under one vast umbrella. His kingdom, as well as the influencing Greek culture, stretched from Egypt to as far as India.

Within this thriving, expansive network new centers of “greek” art sprung up, questioning the previous dominance of Athens as the cultural epicenter of the ancient world. Now, cities like Alexandria, Antioch, and Pergamum began making a name for themselves in the artistic arena. They took the attic ways, but then added local flare or improved technical abilities. By the 2nd century BC, the rising power of Rome also absorbed much of the Greek tradition, all while supplying their own slant or engineering prowess.

So what did the local artists do to the Athenians’ dominant version of ‘ideal’?

Well, they destroyed it in the most magnificent of ways.

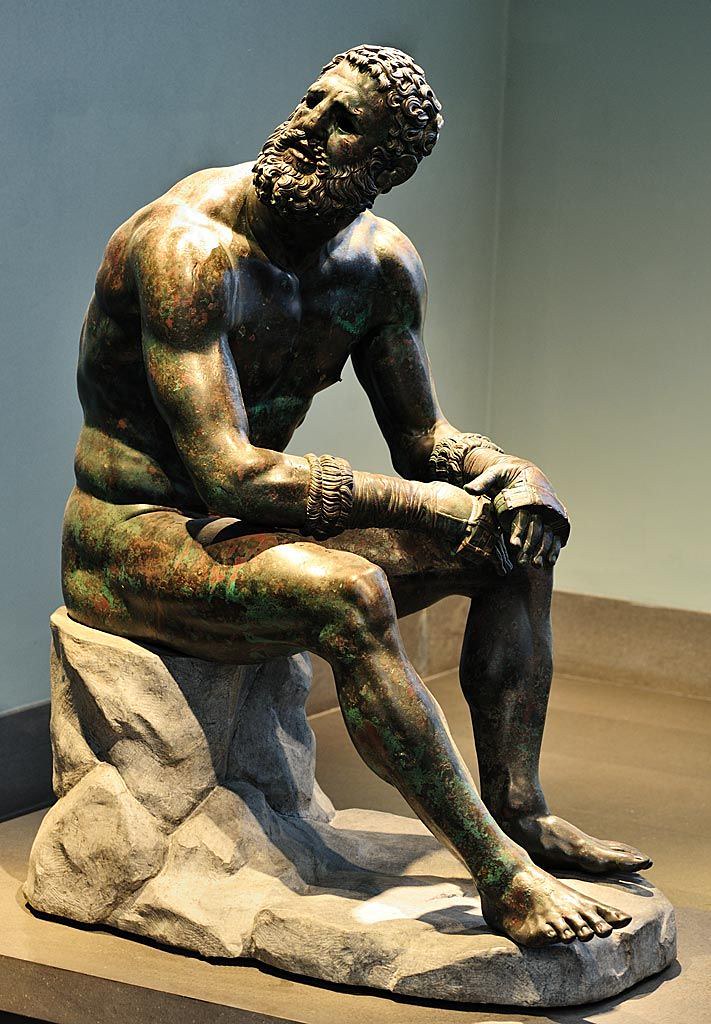

The tall, proud statues found in high classical art were punched, twisted and tortured. They distorted the beautifully sculpted youths of Athens’ golden age into decrepit or dying individuals. Upstanding gods and men were depicted as inebriated, passed out with their legs spread wanton or clutching a bottle.

The artists picked up the old perfect bodies, wrapped gracefully and modestly in sculptured cloths and threw them into the water till they were drenched. The women became erotic, with shapely figures bravely carved through flimsy fabric. They perfected transparency portrayed in stone.

One only has to think of the “Venus de Milo” and the slinky s-like shape of her torso to grasp this new found sensuality. The “Winged Victory of Samothrace”, now atop a dramatic staircase in the Louvre, is breathtaking and triumphant in her clinging cloth.

The Hellenistic sculptures also broke out of their planes, becoming “in-the-round”, or something to be seen from every angle. True to the diversity from which the art was born, subjects reflected a medley of individuals. There were old men and children, africans, sentimental folks and the so called “grotesques”. Emotions, such as agony, kindness or wisdom, were revealed, etched into their faces.

Among the most famous pieces of this time period is the “Dying Gaul“. It portrays a soldier, crippled over in pain. His expressions show his anguish as well as his contorted body. The realism of this piece, which was commissioned some time between 230 BC and 220 BC by Attalus I of Pergamon to celebrate his victory over the Celtic Galatians in Anatolia, is overwhelming.

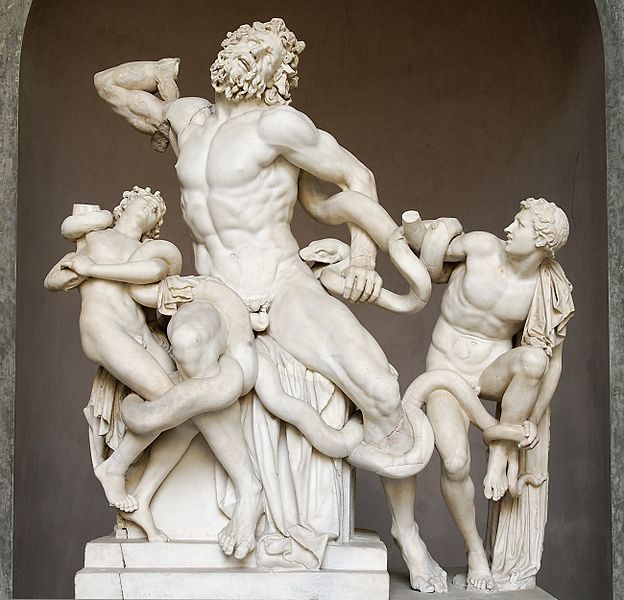

Among the most famous pieces of this time period is the “Dying Gaul“. It portrays a soldier, crippled over in pain. His expressions show his anguish as well as his contorted body. The realism of this piece, which was commissioned some time between 230 BC and 220 BC by Attalus I of Pergamon to celebrate his victory over the Celtic Galatians in Anatolia, is overwhelming.Another exemplary specimen is “Laocoon and his two sons.” The statue depicts a scene from Virgil’s Aeneid, when a priest tried to warn the Trojans against taking in that wooden horse. The Gods on the Greek side sent a snake to punish the prudent man and his sons, which is what we see in stone. These statues are a conglomeration of twisting nudity and pain. The elderly priest, while in excellent physical shape shows true torment on his face. He is a far cry from the noble Apollonian statues of the Classical period or the Kouros of the Anarchic era. This tormented figure is definitely Hellenistic Greek Art.

Eventually this style and period came to an end. The historians like to mark this moment with the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. It was when Octavian, who later became the emperor Augustus, defeated Marc Antony‘s fleet and, consequently, ended Ptolemaic rule. The Ptolemies were considered the last Hellenistic dynasty to fall to Rome.

It was time for another empire, with its own range of diversity, to take place.

This does not mean, however, that Greek art and its traditions completed disappeared. Indeed, they remained strong during the Roman Imperial period, and especially so during the reigns of the emperors Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–14 A.D.) and Hadrian (r. 117–138 A.D.).

This is a wonderful fact for the modern viewer, as many of the astounding works that exist for us today are not in fact, Greek originals. They are Roman. By improving the materials and support systems, the Latin conquerors helped preserve some of the greatest art of the Ancient Greek world.

Pheidias – The Great Greek Sculptor

By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Considered one of the greatest sculptors of all time and producing pieces that are considered masterpieces even today, Phidias’ (or Pheidias) work remains to tantalize our imaginations. Due to the fact that we can only reconstruct some of his works, such as the colossal statues Athena Parthenos or Zeus at Olympia, from copies and descriptions, we truly can only imagine the immense impression that his art must have created for the ancient audience. Outlining the life of Phidias proves to be quite entertaining, peppered with a rise to fame, favoritism, scandal, bribery, and even exile. This all paints a vibrant portrait of the sculptor… however we should be wary of these stories since the majority are anecdotal as opposed to biographical.

Illustration of Pheidias

Pheidias’ Early Life

As with most historical figures in antiquity, exact dates are unknown. However, Phidias is expected to have been born around 490 BCE in Athens. He was the son of Charmides and was trained by other Athenian sculptors. Probable teachers in his early life were Hegias of Athens and Ageladas of Argos. Ageldas, or Hageladas, is suspected to be the reason behind the Dorian style exhibited in some of Pheidias’ work.

Pheidias’ Career and Prominence

In contrast to the scarcity of information detailing Pheidias’ life, we know a great deal about his career and his works. Around 449 BCE, Pheidias was placed in charge of a large building program that was initiated by the Athenian statesman Pericles. This was after the Persian Wars had swept through Greece but preceding the Peloponnesian Wars in the later half of the 5th century. As a part of this mega building project in Athens, Pheidias’ was commissioned for three different works on the Parthenon: the Athena Promachos, the Lemnian Athena, and the Athena Parthenos.

Athena Promachos

Athena Promachos, or Athena who “fights in the front line,” is thought to be one of Pheidias’ earliest works. It was placed on the Acropolis around 456 BC, measuring around 30 feet high. While the statue itself does not remain, we do have a description from Pausanias who tells us that the statue was set up in the open, behind the Propylaea, with her helmet and tip of her spear visible to sailors approaching Athens from around Cape Sounion. The statue itself may have been erected to commemorate the battle of Marathon, in which Athens delivered a surprising blow to the Persian army in 490 BC. Incredibly, we have parts of the base and inscription that Athena Promachos rested on. The statue was destroyed in 1203 AD, but the form has been discovered on a few Attic coins that were minted during the Roman period. For one of Pheidias’ earliest works, it certainly did not lack any amount of sophistication or craftsmanship.

Lemnian Athena

Another statue that was erected on the Acropolis and credited to Pheidias was the Lemnian Athena. Originally worked in bronze, the statue was dedicated and paid for by Lemnos, an Athenian colony, in 451 BC. Again, the original statue has been lost, but we do have a few Roman copies: a head recovered from Bologna and two statues in Dresden. Together, they give us the sense of what the original may have looked like.

However impressive these two preceding statues were sure to have been, little compares to the colossals that Pheidias produced: Athena Parthenos and Zeus at Olympia. Athena Parthenos was completed and dedicated in 438 BC, and was placed inside the Parthenon. She was made of gold and ivory and stood roughly 38 feet tall. And while we still don’t know much about Pheidias’ personal life at the time, we do see him and Pericles represented in the shield that Athena Parthenos holds… a fact that becomes integral to his downfall in the years to come. Again, the original no longer exists, but Roman copies and coinage give us the image of Athena Parthenos that we have today.

Athena Parthenos

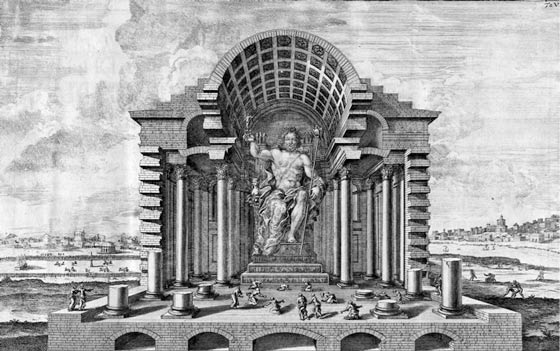

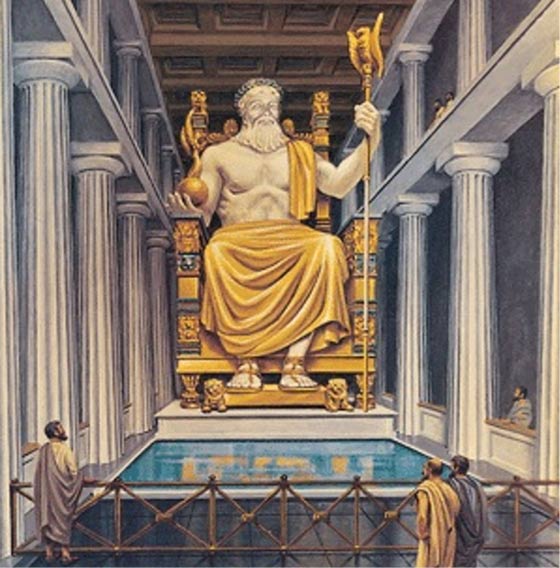

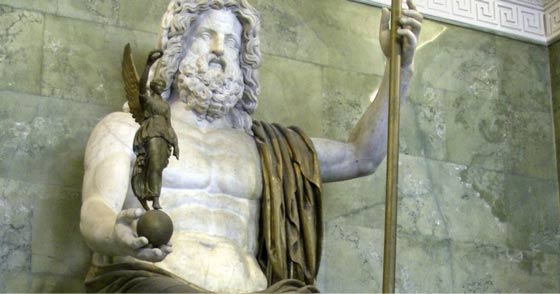

The statue of Zeus at Olympia was Pheidias’ final major project and was completed around 430 BC for the temple of Zeus at Olympia. It too was colossal, clothed in gold, and body made of ivory. It was about 42 feet high and took up the entire height of the temple, with some questioning how the statue even got in the temple in the first place, seeing as the statue came second. The statue of Zeus was highly decorated and painted, adding to the jarring, and somewhat gaudy by modern day perceptions, image of the god. Today, the statue of Zeus is considered to be one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, even though the original no longer survives.

Statue of Zeus

Pheidias’ Death and Legacy

After the statue of Zeus at Olympia, Pheidias seems to have quickly left the public eye as a result of scandal and enemies. Likely due to his close association with Pericles, the Athenian statesman who certainly had his fair share of enemies, Pheidias was a target for plots seeking to get rid of him. One of the reported attacks on Pheidias came in 432 BC when he was accused by Pericles’ enemies of stealing gold from Athena Parthenos during construction for his own wealth. Somehow he was able to defend his way out of this accusation though and nothing much came of it. A few years later, Pheidias was accused of impiety, on the basis of his personal representation (along with Pericles’) on the shield of Athena. For this charge, he was thrown in prison and then likely exiled to Elis. His actual place of death is disputed, with Plutarch writing he died in prison in Athens, while Aristophanes quotes Philochorus saying he died at the hands of the Eleans after he finished the statue of Zeus.

Although we know so little about Pheidias’ life and most of his original work has been lost, he is still considered one of the greatest sculptors of all time. He produced monumental works that took up prominent places, so his exposure seemed to be far above his contemporaries. Pheidias is thought to have ushered in a true change in sculpture style into the classical from any leftover Archaic style. He represents a time of wealth and prosperity in Athens, but also serves as a reminder of the rampant political tensions, ultimately leading to his death.

The Statue of Zeus

By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

What do we really know?

It sounds like something straight out of the Hollywood machine that produced movies like Cleopatra and 300– and in all honesty, it kind of looks like a Hollywood prop piece too. The Statue of Zeus at Olympia has been deemed (rightly so) one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. It stood almost 40 feet high and was outfitted with gold, ivory, precious stones, and sat on a cedar wood throne. In one hand, the statue holds a scepter with an eagle perched on top; the other hand, a statue of Nike. It was placed inside the preexisting Temple of Zeus, which has quite the foundation myth itself. Conjured up in our minds is a statue with the force of nature behind it, inspiring awe and fear simultaneously.

Thousands of years later, we have fragments of the temple, including the pediments, the base of the steps and some columns, but the overall superstructure was ravaged by fire and earthquakes, leaving us with less than ideal remains. Unfortunately, the statue no longer exists entirely, as it was likely destroyed in Constantinople sometime after 426 AD, leaving us with a major gap in the material record that we would love to have filled. Who wouldn’t want to find a gigantic Greek god in all his glory poking out of the ground somewhere? However, this is not more than unlikely, it’s quite impossible.

Statue of Zeus

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia

When talking about the imposing Statue of Zeus at Olympia, you can’t do so without talking about the temple within which it was placed. After all, context is the key to understanding, right? The temple of Zeus was built around 470-456 BCE and was one of the largest on mainland Greece. It was built primarily of local limestone, but Parian marble decorations adorned the facade in Severe and Early Classical style. Later, when restoration and renovation was needed, Pentelic marble was used. The temple provides us with sculptures on the metopes and the West and East Pediments that are truly amazing. The metopes boast the 12 labors of Heracles, while the West Pediment shows the Battle of Lapiths and Centaurs at the wedding of Peirithos. The East Pediment illustrates preparations for the chariot race between Oinomaos of Pisa and Pelops for the hand of Hippodamia in marriage.

The overall impression we get of these depictions is that this is a temple honoring no small feats of strength, power, and man. No, this temple of Zeus reached for the highest caliber of laurels. Fittingly, the statue of Zeus that was commissioned to be placed inside the already existing temple was not to be any ordinary shrine. The statue of Zeus had to be more monumental than the accomplishments and stories of the heroes shown on the outside, making it clear the Zeus was trumping it all.

East Pediments

So how do we know about the statue in the first place? For this, we look to the many authors of Greece and Rome who committed the statue to writing. Strabo said that if the statue stood up, it would have lifted the roof of the temple. Pausanius also provides us with a detailed account of the statue and temple, describing Zeus to be ornamented with olive sprays, robes, intricate carvings, gold and ivory. Perhaps one of the more moving descriptions of the statue comes from Dio, who wrote that “a single glimpse of the statue would make a man forget all his earthly troubles.” It is safe to say that while this statue surpasses our idea of monumental and maybe even toes the line of ostentatious. Clearly, it impacted the very psyche of the visitors and patrons of the temple.

The statue took upwards of eight years to complete, and a workshop was built specifically for Pheidias to build it. Interestingly, we still have remains of what we think is Pheidias’ workshop. Thanks to the extensive literary descriptions we have of the statue, many reconstructions exist. While we can’t ever be sure that they are 100% accurate, it is certainly a great way to get an idea of just how massive and incredible this statue was. Take a look for yourself below and maybe you’ll be inspired to train for the Olympics in honor of this massive god:

When in Rome, Be Greek

By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The Discobolus Lancellotti and a fragmentary statue of the Lancellotti type, Roman copies

Rome: a Mediterranean giant, known far and wide for its conquering and warfare… and its strong penchant for proudly displaying spoils all around the city. For hundreds of years Rome’s military prowess led to Triumphs, civil ceremonies and religious rites paraded through her famous streets. Rome was powerful…and she wanted to make sure her control extended not just to the military, but to the artistic endeavors of the empire as well.

After the Roman Empire conquered Greece and found (relative) stability in their position in the Mediterranean, a certain movement swept through the upper level Romans. Philhellenes – literally friends of Greece- were adamant admirers of Greek culture and everything that went with it. This movement, finding its roots in the literate upper class as early as the 3rd century BCE, led to centuries of cultivating Greek art for Roman consumption.

Map of the Roman Empire

And the Romans absolutely loved it. The sculptures of Greek athletes, the strong and toned depictions of gods and goddesses, the busts of famous philosophers – it all showed beauty and power of a great civilization that was now under the jurisdiction of Rome. The Romans knew that at the height of Greek power architecture, art, theater and philosophy as well as war, politics, and money were valued greatly. They saw the Greek civilization not as defeated or crumpled, but as a narrative of the not so distant past and the potential greatness that they too could achieve.

The Romans respected the Greeks… and that is important to remember.

By the 2nd century CE, the market for Roman copies of Greek sculpture and art was enormous. Casts were made in workshops to “mass produce” pieces of particular interest. Roman artists would morph the two cultures by taking Roman heroes and marrying them with the distinguishable Greek style of athletic sculpture. In the end, wealthy Romans displayed their copies prominently in their homes and decorated their villas, using Greek sculptures as functional and integrated design features of their homes.

This marble made statue is a representation of Octavius, a Heroic Roman General

Again, the Romans absolutely loved it. The copies insinuated education, class, and privilege, and the Romans capitalized on this prestige.

Of course, this wave of philhellenism is very much in line with the Roman style of expansion. As their grip on the Mediterranean oppressively tightened, as far as art, language, and religion were concerned, conquered territories were allowed to continue practicing whatever it was they wanted… as long as they paid taxes, sent men for war, and made sacrifices to the Roman gods. This was how the Romans maintained control on such a massive scale.

Statue of Mars, the Roman God of War

When the Romans spread east over Greece, they recognized and remembered the importance and power of the Greek civilization. Whereas the rest of the empire was expected to learn and speak Latin as a mark of education, the Roman empire allowed Greek to remain the language of distinction in Hellas. The result was: if you were an educated and sophisticated Roman, you knew Greek too.

So, knowing how impressive and respected the Greek civilization was, the fact that the Romans fell absolutely head over heels in love with their art is no surprise. The Roman government effectively used Greek art as political propaganda. They constructed buildings specifically to display imported art and held the Greek spoils a head above the rest. While Rome became a conglomeration of artistic spoils of lands plundered throughout their region, there was just something about Greece that made her stand out. And Rome welcomed it with open arms.