Ephesia Grammata: Magical Words in the Greek World

Written by Ben Potter, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The importance of rituals and temples in the ancient world are hard to clearly differentiate from worship. At first glance this might seen a little odd to the modern reader. These days, it seems perfectly normal for a disinterested secularist to wander around the great cathedrals of the world drinking in their beauty and splendor; they might even fully participate in the festive period–from caroling and dancing to donating to Goodwill.

That it’s harder to imagine this disconnect between worship and ritual in the ancient world is, in a way, quite convenient… as it’s also much harder to analyze due to a lack of source material.

That said, there are some writers who occasionally give us a glimpse into what was in men’s souls.

For example, Polybius wrote:

“The quality in which the Roman commonwealth is most distinctly superior is in my opinion the nature of their religious convictions… These matters are clothed in such pomp and introduced to such an extent into their public and private life that nothing could exceed it, a fact which will surprise many… It is a course which perhaps would not have been necessary had it been possible to form a state composed of wise men, but as every multitude is fickle, full of lawless desires, unreasoned passion, and violent anger, the multitude must be held in by invisible terrors and suchlike pageantry”.

Here, the historian seems to confirm that the vast majority of common/uneducated Romans engaged in ritual practice with a high level of credulity and were not merely going through the motions when it came to showing devotion to the gods on days of ritual worship.

About 250 years prior to this, Socrates, as reported in Plato’s series of dialogues which make up The Last Days of Socrates, stated that the gods aren’t really the ferocious characters we portray them as and are much more akin to a post-Enlightenment Christian idea of god i.e. some form of ethereal ‘good’ or ‘love’.

Indeed, the philosopher even implies that this was a widespread belief—or at least idea—in Classical Athens. Assuming this to be true, it would seem antithetical to believe people would really sacrifice a calf to Poseidon in the hope of a safe sea voyage, but in fact did so instead out of habit or respect for ritual traditions.

Of course it’s worth noting that despite this interesting hypothesis, in 399 BC Socrates was executed for giving air to such seditious thoughts.

Regardless of what was truly believed, it does seem that, throughout human civilization, ritual has often come to supersede the purpose for which it was originally performed (again, Christmas comes to the forefront of one’s mind).

Whilst temples were often used by Greek city-states to show off their own splendor or to ‘one-up’ their neighbors (the Parthenon and the temple of Zeus at Olympia for instance), their primary religious function was as a place around which—though not actually in which—rituals took place.

In the words of Classical scholar Richard Allen Tomlinson, temples were primarily the “house of the god whose image it contained, usually placed so that at the annual festival it could watch through the open door the burning of the sacrifice at the altar which stood outside”.

Accordingly, we can state that temples’ primary function was facilitating the rite of animal sacrifice (or/and vice versa). And it is such rites—i.e., individual acts of worship or devotion—that go together to make up a ritual.

If this all feels a little bit vague and unclear then… well done, you are getting the grasp of ancient ritual perfectly – the definition of ritual amongst sociologists is hotly debated even to this day.

According to Fritz Graf (the distinguished Classicist, not the former NFL referee): “ritual is an activity whose imminent practical aim has become secondary, replaced by the aim of communication…form and meaning of ritual are determined by tradition; they are malleable according to the needs of any present situation, as long as the performers understand them as being traditional”.

Our old friend, Lack of Source Material, is problematic for one wishing to delve deeply into ritual in antiquity because, as is intuitively obvious, there was no need to chronicle the repetitive, humdrum rituals of daily life.

What was much more noteworthy was when ritual strayed from the beaten path; such instances, however, usually generate more questions than answers. Moreover, the key vehicle for acquired ritual wisdom in Greece and Rome was oral and not written tradition.

(The so-called ‘magical papyri’ uncovered in Egypt in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are commonly considered to be the exception that proves this rule.)

Preparations for a Sacrifice, fragment from an architectural relief, c. mid-first century C.E., marble, Musée du Louvre, Paris

As already mentioned, perhaps the most important (or, at least, most dominant) rite of ancient ritual was animal sacrifice. Though it was not unknown to immolate an entire animal for the benefit of an esteemed deity, to destroy a precious beast of the field was wasteful in the extreme.

Whilst it seems the sacrifice itself – a life taken and blood spilt – was sufficient to satisfy most, an immolation of the choices cuts would likely have been enough of a respectful gesture for even the most pious observer.

Echoes of this practice still exist in mainstream modern monotheism, both literally (the process of halal sacrifice) and symbolically (Christian Eucharist).

Obviously, it would not have been expedient for an average citizen to sacrifice an animal any more precious than a chicken, so the slaying of sheep, goats and, if the occasion were grand enough, cows became a communal and festive ritual act.

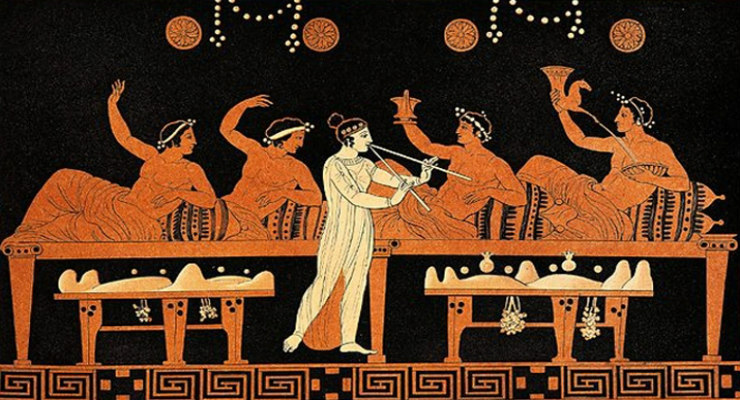

Indeed, one simple reason for why so many people looked forward to days of ritual sacrifice was because of the feasting (and drinking) that would accompany it.

This is not to say that individuals of moderate or meagre wealth did not sacrifice; however, they were more likely to offer cakes, grains and fruit or to pour libations of wine, milk or oil.

Again, modern parallels abound—many devotees of Buddhism daily adorn their altars with flowers, rice, water and, increasingly, sugary soda drinks. Likewise, Catholic altars throughout Central and South America are equipped with regular contributions.

Another common, important type of ritual documented in antiquity were those to remove ‘pollution’ i.e. the invisible, though very real, consequences of the traumatic extremes of the human experience such as birth, death, murder, madness, sickness, cannibalism, incest, and blasphemy.

There is also a variety of initiation rituals that are, mostly, not only unknown, but unknowable. The most beguiling, horrific and vivid image of such a rite is rumored to be part of the cult of Mithras (a deity with many aspects in common with Jesus Christ) in which the initiate stood beneath a wooden lattice upon which a bull was sacrificed and the blood of the animal washed over them. However, this macabre baptism does not have enough corroborative evidence to be taken without a pinch of salt.

Regardless of the cause or practice of ritual in the ancient world, it is undeniable that it played a hugely significant part both in day-to-day life, and, more importantly, in the fate of how history came to be governed.

Specifically, it was manipulated by dictators and tyrants to legitimize and underpin their reign.

Indeed, it is very difficult to imagine that Augustus, the man who wrenched the façade of democracy out of the cavity of the Roman Empire could have prospered as he did without manipulating ritual so brilliantly and cynically (the funeral of Julius Caesar, the imagery on the Ara Pacis, his mausoleum, his abode on the Palatine Hill…the list seems inexhaustible).

The fact that ritual underpinned the authority of the Roman emperors is why, when Christians flouted such observances, they were not merely rejecting the gods of old, but the very authority of the supreme ruler himself.

And it was this monumental clash of religions and rituals that brought about not only the dissipation of the ultimate authority of the emperor, but an irreconcilable and irreversible revolution in the history of the European people.

By Ben Potter

If I invited you to a bacchanalia what would you expect? Wine? Dancing? Sex? Of course you would. How about harmonizing with nature? Mass hallucination? Violence? Carpaccio? You’re beginning to think you should call and cancel, aren’t you?

Well don’t worry, it might not be as wild as you think. Then again, it might be much worse. The ancient Athenians, like you and I, did not seem to have a crystal clear idea of what constituted a bacchanalia.

This reason for this is simple – it was a secret. Well, a mystery to be precise.

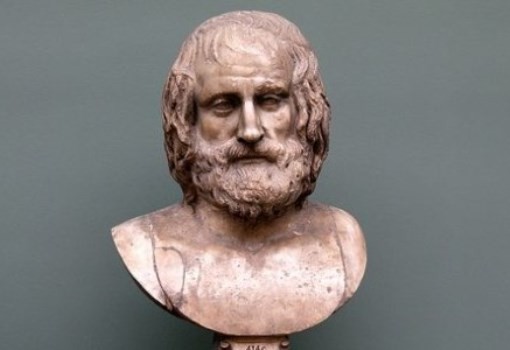

The shroud of secrecy that hung over these proceedings is appropriately reflected in Euripides’ The Bacchae. Appropriate because, despite a straightforward plot, The Bacchae is probably the least easy of Euripides‘ extant plays to analyse. Written in Macedon and performed posthumously in Athens, the story is simple:

Pentheus, the king of Thebes, had banned all worship of his cousin Dionysus. Dionysus decided to wreak revenge. He sent the women of the city mad with devotion and forced them out into the glens of Mount Cithaeron. These women were his ‘Bacchae’. Pentheus wanted to arrest all the Bacchae and execute the ‘effeminate foreigner’ (Dionysus in disguise) who was exciting them. Dionysus was arrested, he escaped, and then escorted a brainwashed (and transvestitized) Pentheus into the countryside to watch the sexual exploits of the Bacchae.

Far from getting his free peep show, Pentheus was torn limb from limb by the revellers led by his crazed mother, Agave. Agave brought the head of Pentheus back to the city and everyone agreed that it had been a mistake to disrespect Dionysus.

So where lies the problem? Well, it lies in the message. Quite simply, there isn’t a great deal of consensus as to what it was.

A lot has been made of the conspicuous absence of sex in the behavior and dialogue of Dionysus. It is Pentheus who seems obsessed with this element of the dionysiac experience. And indeed, it is this obsession that leads to his death. Before the opportunity to spy on the worshippers arises, Pentheus, though in the wrong, is strong and steadfast in his opposition to Dionysus.

Death of Pentheus

However, Pentheus is actually dionysiac by nature – as, of course, his blood would dictate. Failure to repress, or fully submit to this leads first to the loss of his authority and, ultimately, to the loss of his life.

What this treatment of the sexual element means is unclear. Was Euripides trying to convey that the worship of Dionysus was more than merely about sex? Was he pointing out that the reputation of the mystery cult in Macedon was different to that in Athens?

Another theory is that the play is a deathbed repentance of a man recanting all his years of blasphemy.

However, this is hard to believe as Dionysus is portrayed as a creature of horror, violence and cruelty. Not content with justice, but desirous to carry out torture and humiliation.

We witness this when the citizens of Thebes see their addled king being marched through the streets, emasculated in women’s garb. On his return both the clothes, and the body they covered, have gone. All that is left is a severed head clutched in the hands of his frenzied mother.

Whilst there is a call for piety, it feels more borne of pragmatism rather than of true belief. Cadmus, grandfather of Pentheus and Dionysus, states: “Mortals must not make light of gods – I would never do so”.

His words are given extra weight as he, along with Teiresias, are the only noble and wise characters in the play. He continues with a criticism: “Dionysus, god of joy, has been just, but too cruel”. Whilst the Chorus chime in with: “Cadmus I grieve for you. Your grandson suffered justly, but you most cruelly”.

The emphasis is not on hubris or blasphemy, but on the folly of upsetting a powerful enemy. This is tantamount to the willful abandonment of wisdom, something which many believed was at the root of key social and political problems in Athens.

Dionysus himself explicitly states: “If you all had chosen wisdom, when you would not, you would have found the son of Zeus your friend”. This is perhaps the most convincing of the possible messages. Not least because it is consistent with the lifelong views of Euripides.

This play was written far away from the war-obsessed, bereaved, bankrupt and exhausted world of Athens, at a time when the Peloponnesian War was in the process of being lost.

Whether Euripides was a bitter exile or a content expatriate we cannot know, but his distance, together with his advanced age, may have given him greater urgency and freedom.

So, was the play a warning to the city?

A warning to be pious seems disingenuous, but perhaps that is what it was. Regardless of his religious beliefs, Euripides knew most Athenians exhibited signs of true belief. Is he, therefore, using religion to manipulate the believers? In doing so, trying to highlight the folly of war, trying to bring an end to the carnage?

Bust of Euripides

It is unusual to have a god, a true god – not a Heracles figure, dominate the action. Tragedy is filled with gods, but they are usually behind the scenes, pulling the strings, causing or resolving problems out of mortal control.

Religion and violence are clearly important aspects of The Bacchae. However, it is difficult to understand if the former is being used to explain, excuse, or warn against the latter. We certainly see extreme and brutal violence in Pentheus’ punishment. Also, he says he wants to ‘hunt’ the Maenads (the female followers of Dionysus) and has desires to execute the effeminate foreigner by stoning, hanging or beheading.

As Teiresias puts it: “Come Pentheus, listen to me. You rely on force; but it is not force that governs human affairs”.

Is Euripides emphasizing peace, piety or wisdom? Some traditional commentators consider the three interchangeable, each impossible to achieve without the others.

Something we must bear in mind is that Euripides knows he won’t be around much longer. He’ll no longer be there to tell people how to think, to point out the error of their ways. If he can persuade his estranged countrymen to think for themselves, to think logically, calmly and peacefully, then perhaps he can die with some hope for Athens.

Prophet Teiresias

More superficially, there is the idea that Euripides thinks Athenians are simply taking life too seriously. The fifth century is a time of serious thought, of democracy, logic, laws, expansion and building. Perhaps Euripides, reflecting from his position of remote tranquillity, thinks everyone should be a bit more dionysiac, should do what feels good.

We again turn to Teiresias for support: “Men have but to take their fill of wine and the sufferings of an unhappy race are banished…This is our only cure for the weariness of life”.

Or simply, sadly and quite subtly, the play might be an introspective look at the life of a lonely exile, a man who misses the acropolis and agora of Athens. Cadmus could easily have been our playwright in disguise: “What utter misery and horror has overtaken us all…in my old age I must leave my home and travel to strange lands”.

You may see this play as a belated adoption of religion, a drive for peace, the plea of an educated man desperate for his fellow citizens to think, the lament of a heartbroken exile who misses his homeland, or simply an encouragement for us too to dance, drink and be merry. Whichever way, hopefully the overriding conclusion drawn from The Bacchae is that this is a truly fascinating piece of theatre from the mind of an undeniably extraordinary individual.

Interested in reading the twisted tale of The Bacchae by Euripides? You can access it here for Free: https://classicalwisdom.com/greek_books/Bacchae/

“The Bacchae: the Morals of Murderous Women” was written by Ben Potter

By Edward Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

The modern world owes so much to the Greeks and the Romans, they influenced how we live and our society in so many ways. For instance, now we think that Christmas is a very Christian festival, celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ, but in fact, the holiday was greatly influenced by the pagan Greeks and Romans… in more ways than one.

Ancient Greece and Christmas

Every society has religious festivals that are accompanied by feasting and celebrations. The Greeks were no different. The ancient Greeks regularly celebrated festivals in honor of the Olympian deities they worshipped. One of the most popular religious festivals was held for the god Dionysus, the Olympian god of wine, fertility, pleasure, festivity, delirium and frenzy. This god was something of a shapeshifter and he was often portrayed as either an old man or an effeminate youth. This ability meant that he was also the god of drama and the theatre. He was a very popular god with the ordinary people and so every year they held a celebration in honor of the god of wine on December 25th or the 30th.

Like Jesus, Dionysus was born to a Virgin, regarded as a redeemer god by many, and the festival in his honor was related to the birth of the winter sun. His birthday was marked with feasting and possible present giving. There were many hymns to Dionysus sung at this time, mainly by choirs of children, which is rather similar to modern Christmas carols.

the Self-Portrait as Bacchus, is an early self-portrait by the Baroque artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, dated between 1593 and 1594.

While the birthday of Dionysus has very many similarities with the celebrations around the birth of Jesus Christ, some scholars believe that The Kronia, an Athenian festival held in honor of Kronos and was noted for its feasting, was also one of the inspirations for the Christian festival.

Ancient Rome and Christmas

Christianity started as a sect within Judaism, but changed radically over the centuries. Despite persecution, it was able to flourish within the Roman Empire. The Christians were often loud in their condemnations of the Romans as sinful, but in fact, they were also greatly influenced by them. It is widely agreed that the Roman festival of the Saturnalia was highly influential in the development of the Christian holiday of Christmas.

Early Christians

Saturnalia was held in honor of the god Saturn, the god of agriculture, wealth and plenty, and this celebration ran from the 17th of December through to 23 December, as corresponds to the modern calendar. This festival was marked by sacrifices to the god and a lavish public party. It is possible that at one time there were human sacrifices to the Saturn, but these were later replaced by effigies of human figures. There was also a lot of gift-giving between neighbors and family members.

Partying and public drunkenness during the festival was common and everyday social norms were overturned. Indeed, the traditional hierarchy itself was subverted. Slaves were served by their masters and the ordinary people took great liberties. There was a great deal of promiscuity and it is alleged that women could sleep with whomever they wish. Moreover, many things that were illegal during the rest of the year were tolerated during the Saturnalia, such as gambling. Once the festival was over, however, Roman society returned to the traditional social norms.

Christianity and the Saturnalia

The Christians naturally hated the festival that was held in honor of the Roman Pantheon’s King of the Gods because they viewed them as promoting immorality and sin. The festival was denounced by many Christian apologists and saints, but nevertheless, Saturnalia was very popular, not only in Rome but throughout the Roman Empire. Over time Christians decided to adopt Saturnalia because they knew that it was so popular with the people that they could not simply ban it.

Meanwhile, the exact birth of Jesus Christ is not known and it is not mentioned in the Bible. December the 25th was selected by the Early Church in order to associate the birth of the Christian redeemer with Saturnalia. It was the Christian leadership’s attempt to Christianized Saturnalia and her Roman celebrants and to a large extent, they were successful. However, people continued to celebrate Saturnalia and the birthday of Jesus at the same time for many years.

Over time the Christian Church was able to completely Christianize the pagan festival. However, elements of Saturnalia remained, as seen by the tradition of the Lord of Misrule in many European countries. This was a time when the social norms were suspended and outrageous behavior was acceptable, just as in the time of Saturnalia.

Whether it was to honor Dionysus, Kronos or Saturn, the Greek and Roman traditions live on in our modern Christmas celebrations, and that’s something to remember at your next Christmas party…

References

Count, Earl W (1997)4000 Years of Christmas: A Gift from the Ages. NJ: Ulysses Press

By Van Bryan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Wining and dining — and philosophizing — is the way the Ancients celebrated life. In fact, wine was a cultural staple for the ancient Greeks. Considering that their civilization is the foundation for much of western civilization, wine becomes an important part of our collective heritage.

Archaeological digs that have unearthed extravagant, presumably once wine-toting goblets dating as far back as the Mycenaean era of Greece. Such artifacts included gold and silver goblets that demonstrated that the people of the Mycenaean era were not only fierce warriors, but also people of sophistication who were aware of wine and respected it greatly.

One artifact of particular interest is the Cup of Nestor. This Golden goblet was discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876 in the ancient civilization of Mycenae. It is believed to have belonged to the ancient king Nestor of Pylos, who was a prominent character in The Iliad.

Homer describes the goblet of Nestor as follows:

“There were four handles on it, around each one a pair of golden doves was feeding. Below were two supports. When that cup was full, another man could hardly lift it from the table, but, old as he was, Nestor picked it up with ease.” — The Iliad

The Cup of Nestor or dove cup is a gold goblet discovered in 1876 by Heinrich Schliemann in Shaft IV of Grave Circle A, Mycenae.

It is commonly held that large scale production, distribution, and consumption of wine began on the prominent island of Crete. Depictions of primitive wine presses can be seen on the walls of Minoan tombs dating as far back to 3000 BCE. Clay goblets and carafes have been uncovered across the island, including in the ancient palace of King Minos in the city of Knossos.

It is believed the craft of wine making began on this island and slowly made the transfer to the mainland of Greece. The ancient Greeks traded wine as a commercial product for centuries across their regions.

Indeed, Greek wine was traded throughout the entire known ancient world. Wines from islands such as Crete, Rhodes, and Lesvos were especially popular. Homer himself writes about the wonderful supply of wine found in cellars outside the city of Troy. The Aegean was so saturated with wine trading ships that Homer would refer to it as “the wine-dark sea”.

Were the wine-dark seas from wine?

In order to accommodate high demand, the ancients developed new wine storage techniques that enabled it to be transported long distances without spoiling. Before the time of air-tight glass bottles, wine left in a regular barrel would be exposed to oxygen and spoil quickly.

The ancient Greeks began the practice of sealing these wine barrels with pine resin to prevent it from spoiling. The resin helped make the barrels air-tight while simultaneously adding a distinct pine aroma to the drink.

This distinctive taste is still alive today in the form of “Restina”, a modern white wine that emulates the flavor of ancient times.

Restina… not everyone’s cup of wine…

An interesting anecdote claims the use of pine resin was for a very different reason. According to this theory, Roman soldiers would regularly plunder the cities of Greece and make off with their stores of wine. The Greek citizens became so angry that they began using pine resin to add a bitter aroma to their wine. The Roman invaders would try one sip of this distinctive wine, taste the bitterness and assume it was spoiled.

In this way the Greeks would keep their wines and the invaders would be none the wiser. This idea would seem to lead to the thought that the Greeks would take measures to protect their wines while the invaders would make off with their women and treasures. At least they had their priorities straight…??

Wine in ancient Greece was of enormous cultural significance. The ancients drank wine to praise the gods and expand their minds. They studied it intently to decipher it’s presumed health benefits and risks.

It was a nutritional staple, a religious experience: indeed, the production, distribution, and consumption of wine is so deeply ingrained with the culture of ancient Greece, that you simply can not have one without the other.

By Mary E. Naples, M.A.

Thesmophoria, the feminine fertility festival, dedicated to the Goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone, was literally for women only. Citizen males of ancient Greece were unconditionally restricted from attending any portion of the three-day long event, though they were responsible for its expenses. Further, men who spied on, or interrupted, the Thesmophoria were subject to life threatening and disfiguring acts of violence perpetrated by the Thesmophorians themselves.

Various Ancient Greek costumes; right to left – One female flute player and the rest are women’s everyday costumes. Date: circa 500 BC

There are some noteworthy examples demonstrating this extensive retribution, straight from ancient sources.

First there is the lore that the hapless King Battos of Cyrene—famed for founding Cyrene—was cruelly castrated by the furious disciples for surreptitiously observing their sacred and secret rites.

Then there is the tale related by Pausanias (110 CE- 180 CE) of the legendary Messenian hero Aristomenes, who was celebrated for his victories with the Spartans. He unfortunately captured the female disciples in the midst of their clandestine celebration, only to be “knocked senseless” by their sacrificial knives and spits.

A girl saves Aristomenes by Franc Kavčič

Next, there is the legend of unlucky Militiades, who, while in battle to secure the island of Paros, leapt over the wall leading to the Thesmophorian shrine. Once there, he was so overcome with terror that in jumping back over the wall he sprained his thigh, from which he developed gangrene and later died. Herodotus (484 BCE- 425 BCE) recounts this as an admonishment, and warms that this mournful outcome was due to his breaching the sacred sanctuary of Demeter Thesmophoros.

Then we have Plutarch’s (46 CE- 120 CE) narrative of Pesistratus (562 BCE -527 BCE), the tyrant of Athens, and the Athenian statesman Solon (638 BCE-558 BCE). They pulled a trick on the Thesmophorians celebrating in Megara by enlisting two beardless men to impersonate the disciples.

Illustration from 1838 by M. A. Barth depicting the return of Peisistratos to Athens, accompanied by a woman disguised as Athena, as described by the Greek historian Herodotus

Once discovered, the Thesmophorians brutally attacked the wretched mimics.

Finally there is Aristophanes’ comedic satire Thesmophoriazusae or “Women of the Thesmophoria.” In it Aristophanes casts his colleague Euripides as the character for whom the Thesmophorians want revenge.

“Today at the Thesmophoria the women are going to liquidate me, because I slander them,” cries Euripides.

The premise is that the rebellious disciples seek to kill Euripides for characterizing women in his plays as villainous. While the women are mocked in terms of their democratic assembly and their ritual, Aristophanes’ depiction of the Thesmophorians as uncontrollable and violent is in keeping with the androcentric mindset towards the festival.

Apulian krater with scene from Thesmophoriazusae, c. 370 BC

The brutality of these stories demonstrates that men’s profound uneasiness with the Thesmophoria was in direct proportion to their wary respect for it. Though suspicious, pious citizen males could not obstruct it, as it was deemed both holy and integral to the health and well being of the polis. Indeed, the citizen males considered the Thesmophoria to be at once both threatening and reverential. Why else, but for the power to increase fertility, would the males in patriarchal ancient Greece comply with the wishes of the obviously inferior sex? In a society where men set the rules, the Thesmophoria turned the dominant paradigm on its head.

Kept from all activities in the public sphere, citizen wives were only granted a watered down citizenship, which simply allowed them to bear citizen males.

Disenfranchised from participating in the political life of the polis, women were similarly as powerless in any acts of societal sacrificial violence. For example, women usually had no access to instruments of sacrifice such as the all-important knife, kettle or the spit. However, archaeological and literary evidence suggests that full-grown sows, killed in a sacrificial manner employing a knife, were discovered at various Demeter sanctuaries throughout Attica.

Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone

Indeed, most scholars now concur that the Thesmophoria was unique in being one of the only feminine festivals where sacrifices were performed, meaning that the women of the Thesmophoria had rare access to the violent instruments of death.

Meeting outside the androcentric social constructs of family; the disciples were at liberty to become autonomous individuals without concerns for their family, as they once were in pre-patriarchal times. It also empowered a united feminine community without male restrictions—a possibly dangerous and subversive combination for the dominant male culture of ancient Greece. Indeed, enfranchised men were afraid of the anger of the subjugated female. And they should have been – for the women at the Thesmophoria, independent and armed at their secret cult festival, were a force to be reckoned with.