By John Mancini

The original sword-wielding dragon slayer of legend was not the knightly Orlando saving Angelica, nor was it Sigurd killing Fafnir… And it wasn’t even the Archangel Michael or St. George.

It goes much further back than all of those… straight to the Ancient world.

In fact, the ancients had a fairly well-documented obsession with snakes, especially the large fire-breathing winged variety. From India to Egypt to Peru, a plethora of cultures around the world had some version of a snake-myth.

It was in Classical Greece, however, that the story elements were arguably perfected (at least in our opinion). There, the dragon-serpent antagonist was none other than the primeval water god, Poseidon, a close relative of Gaia, the earth goddess. He was, you could say, from the beginning of their time.

But what good is a story with the ideal ‘bad guy’ without the perfect hero?

Not much according to Ancient Greek mythology, which supplied some fantastic examples of monster vanquishing champions for us to cheer on.

So, without further adieu, let us look at the five original weapon-wielding dragon slayers from Greek mythology…

1. Apollo

Our first hero was more than just a man, but a god all together. Where better to start really, than with one of the most famous and favored of the Olympians, Apollo, the god of light and the sun, truth and prophecy, healing, plague, music, poetry, etc, etc.

His story begins with his house of worship: the temple of Apollo at Delphi. Appearing on coinage for centuries and supremely important to every culture that knew it, the temple was rebuilt five times in its several thousand year history.

In fact, the earliest version of the temple predated Homeric poetry and was likely devoted to an earth deity, not so dissimilar to our antagonist Poseidon, who was thought to be the most ancient possessor of the oracle.

Funnily enough, it was also supposedly the “earthshaker” Poseidon who was responsible for the earthquakes that destroyed the temple time and time again.

According to the mythology, a spring nearby the location of the temple was guarded by the large Python or she-dragon, which Apollo slayed upon arrival, thus freeing the people from their fear of the earth and its power.

After Apollo’s triumph at Delphi, the traditional omphalos (a rounded stone artifact and early focal point of the temple) came to feature a snake wrapped around it.

This marked it as a symbol of Apollo, the dragon slayer, god of wisdom and healing. The last trait he passed on to his son, Asclepius, who, according to Ovid, transformed into a snake and founded Rome.

2. Cadmus

The second dragon slayer on our list is Cadmus, a Phoenician prince who introduced the alphabet to Greece around 2000 B.C. On a quest to find his sister, Europa, he stopped at the Delphic temple to consult Apollo’s oracle, which led him to found the city of Thebes.

While building the Theban temple, Cadmus’ assistants were slain by a dragon as they attempted to collect water from a nearby spring. (Apparently dragons like hanging around springs.) Athena instructed Cadmus to slay the dragon and then sow its teeth into the ground like seeds. These seeds then grew into a fierce army.

Following Athena’s orders yet again, Cadmus threw a stone into the center of the advancing warriors, causing them to attack each other until only five remained. With these men, or Spartoi, he was able to complete the citadel.

Unfortunately for Cadmus, this wasn’t just any dragon; it had been sacred to the god Ares.

After its death, Cadmus had to do eight years penance, but was plagued nonetheless by the slaying. Cadmus’ family, as well as the city of Thebes, was cursed with innumerable tragedies, including the death of his four daughters and the fate of his grandson, Oedipus.

Eventually, overcome with his misfortune, he exclaimed that if the gods loved snakes so much, then he wished to become one. Ovid claimed that Cadmus and his wife Harmonia then turned into the reptiles and slithered away into the forest together. Other versions of the myth, however, say that the gods transformed them into snakes as punishment.

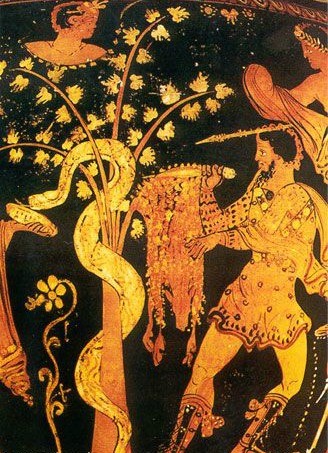

3. Jason

Our next dragon slayer is just like a comic book hero. His team, the Argonauts, were a seafaring crew that included Heracles, Asclepius, Orpheus, and Atalanta, among dozens of others. These larger than life lads accompanied Jason in his heroic quest for the Golden Fleece, which was, of course, guarded by a dragon.

Jason was sent by Poseidon’s son, Pelias, to fetch the Golden Fleece. Along the way, he acquired additional tasks: to plow a field with fire-breathing oxen, to steal a tooth from a dragon, and to slay the dragon that guarded the fleece.

Luckily for Jason, his lover Medea was trained in Hecate’s dark arts and gave him an ointment that would keep him from being burned by the oxen, in addition to a herbal potion with which he could put the dragon to sleep.

He did as advised and stole the tooth from the sleeping monster. Then, like Cadmus, he sowed the dragon tooth into the field, which grew into an army… and, again like Cadmus, he threw a rock into the middle of the crowd. Not knowing where the blow had come from, the army once more turned on each other and self-destructed.

In one version of this myth (and there are many), Jason is swallowed and then regurgitated by the dragon, thus reborn a bonafide hero.

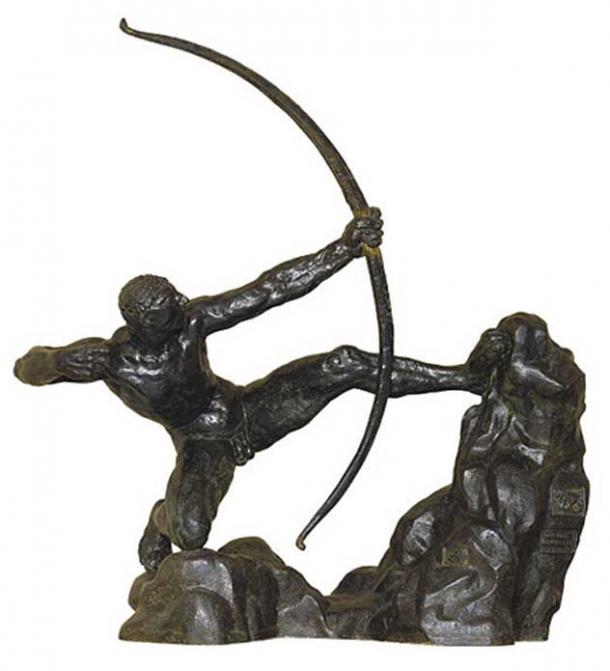

4. Perseus

Next up is Perseus, the legendary founder of Mycenae and of the Perseid dynasty of Danaans. In fact, Perseus’ deeds were so grand that they went on to provide the founding myths of the Twelve Olympians, a first of the heroes of Greek mythology.

Of his conquests, one of the most memorable is the beheading of Medusa, the snake haired gorgon, with the aid of Athena’s polished shield. Afterwards, Perseus went on to slay another monster, the sea serpent Cetus sent by Poseidon.

This time it was to save Andromeda, his prize for slaying both dragons.

It is interesting to note that Cetus is essentially another aspect of Poseidon (being sent by him) and Medusa is often thought to be representative of nature’s wrath, something for which the sea God is notorious.

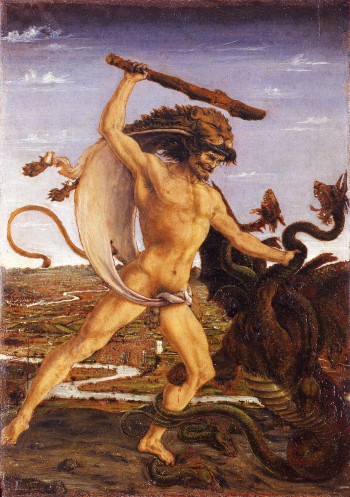

5. Heracles

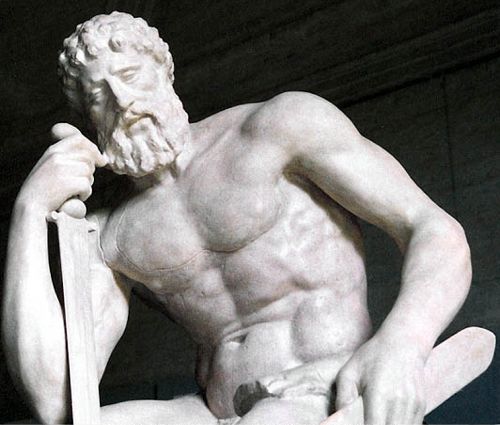

The most accomplished of the Greek dragon slayers, Heracles, strangled his first snake when he was still just a baby in the cradle. Exhibiting strength, courage and ingenuity, he is considered the greatest of the Greek heroes, especially by the many Roman emperors who came to identify with him.

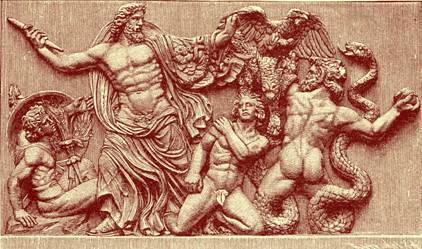

Heracles, in Greek, is another name for the sun. He is the ruler of the zodiac who rings in the new season by continuously slaying the old. Throughout his twelve labors he conquered two multi-headed snakes, including the Hydra and the Ladon.

In an interesting relationship to Jason’s and Perseus’ story, Heracles was instructed for his tenth labor to capture the “golden haired” cattle of the triple-headed Geryon (the son of Chryasaor, who, like his grandmother Medusa, lived on an island at the far edge of the western sea).

Besides mirroring Perseus’ earlier victory over Medusa, Heracles’ slaying of the Geryon follows as all his labors do… the archetypal pattern of the hero’s journey to slay the metaphorical dragon.

This, of course, begs the question: what does dragon slaying represent?

Of course we can never be certain, but it could be seen as a symbolic act of taming the wild, the natural, the demonic. Living in water but breathing fire, with the ability to swim as well as fly, the dragon embodies all the natural forces the ancients would have feared. Slaying them, meant slaying fear itself.

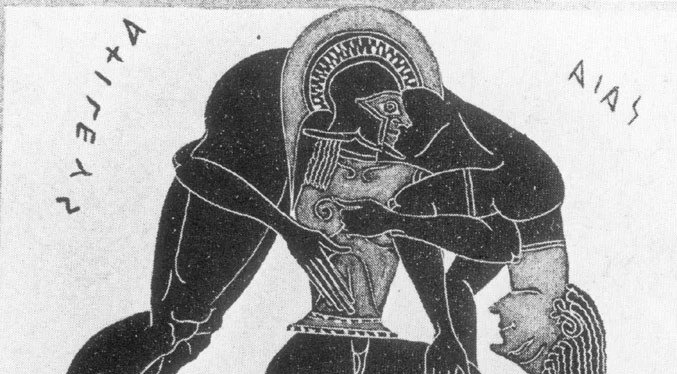

If you guessed Superman, you’re correct. If you guessed the Ancient Greek hero, Herakles, bingo: right again. DC Comics’ Man of Steel is right out of Classical myth, and he’s not the only one. There’s Batman, an ordinary kid turned extraordinary crime fighter, defying the justice system to avenge his murdered father — just like Orestes. There’s Phoenix from X-men and Achilles from the Iliad, two unstoppable renegade live-wires who throw devastating temper tantrums before saving the day in a doomed blaze of glory.

If you guessed Superman, you’re correct. If you guessed the Ancient Greek hero, Herakles, bingo: right again. DC Comics’ Man of Steel is right out of Classical myth, and he’s not the only one. There’s Batman, an ordinary kid turned extraordinary crime fighter, defying the justice system to avenge his murdered father — just like Orestes. There’s Phoenix from X-men and Achilles from the Iliad, two unstoppable renegade live-wires who throw devastating temper tantrums before saving the day in a doomed blaze of glory.