A good story grows like a tree, upwards, seeking the sun and light. Its heavy branches, though substantial on their own, become stronger and more intriguing as plots and characters entangle. Additionally, deep below the bark and greenery, a parallel network of criss crossing roots holds up the story for all to see. The grander the legend, the larger and more intricate its backstory.

A tale on the scale of The Iliad, therefore, has an astounding myth to proceed it.

To know the roots of Homer’s epic poetry, one must dig very deep into Greek mythology… all the way to the first king of Gods and the ruler of Titans, Cronus. Despite his many attempts to prevent it, Cronus was eventually overthrown by his son, Zeus. In the process, Zeus was warned that one day he too would be replaced, just like his father.

At the same time another prophecy emerged, suggesting that the son of Thetis, a sea-nymph with whom Zeus was enamored, would become greater than his father. Zeus, therefore, ordered that Thetis should be betrothed to an elderly human king, Peleus son of Aiakos.

And so there was a wedding, attended by all the glorious gods and goddesses, except one. Eris, the goddess of Discord was not allowed in, for fear she would cause her usual irreparable damage. Her discordance, however, was not to be limited by a gate. Upon her dismissal, she threw a golden apple into the festivities. On it was inscribed the following: καλλίστῃ, meaning “To the fairest”.

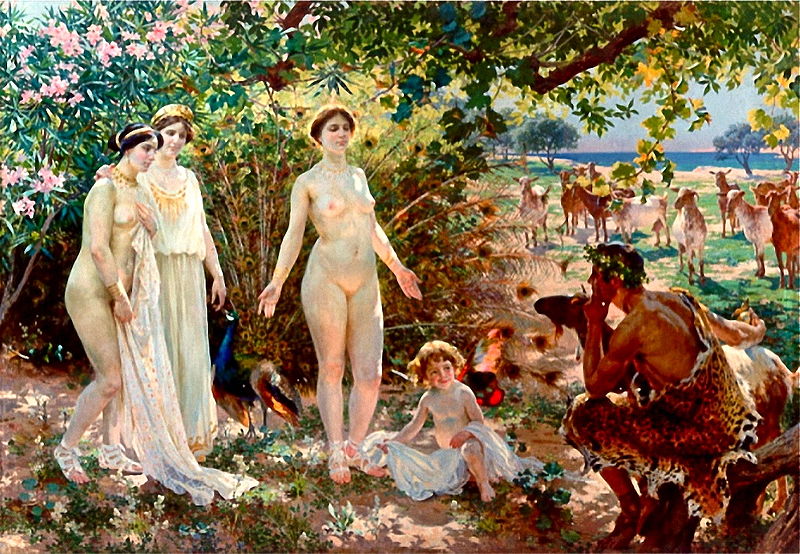

Naturally three gorgeous goddesses claimed ownership. Hera, Athena and Aphrodite all assumed that they were the most beautiful. The other gods and men, however, smartly chose to remove themselves from the decision making process, including Zeus himself. No one wanted to incur the wrath of the other two. Instead the unenviable task was placed on the shoulders of one Trojan prince, a man named Paris. The poor fellow was unable to make a decision and so the goddesses, keen on winning, resorted to offering bribes.

Wisdom and great skill in battle were Athena’s promised rewards.

Hera tried to lure Paris with power and control over all of Asia.

Aphrodite, however, used the best bait of all: The most beautiful woman in the world would be in love with Paris if he nominated the goddess as owner of the golden apple.

Paris accepted.

Meanwhile, the wedded sea-nymph Thetis and her elderly husband bore a child by the name of Achilles. The young boy was given an intriguing destiny. He had the choice to live a long and uneventful life or to die young in glory and live forever in poetry. Achilles would chose the latter.

Thetis wanted her son Achilles to be immortal and invisible and, depending on the version, used different techniques to make this so. One source claimed that she lifted the child by the foot and immersed him in a river which ran to the underworld. Wherever the water touched him, Achilles was made invulnerable, everywhere except where his mother held him… his infamous heel.

While Achilles was growing into a hero-worthy man, Paris was eagerly awaiting his award for crowning Aphrodite the fairest of them all.

The reader may be wondering, who was the magnificent creature that the goddess of beauty promised to the Trojan prince? It was none other than Helen, whose face would eventually launch a thousand ships. Helen was the daughter of Tyndareus, King of Sparta and a woman named Leda, who had either been raped or seduced by Zeus when he was in the form of a swan.

Helen, in her radiance, had many suitors, and her father could not decide which one was best… plus those who who were not chosen might retaliate against him. Eventually one quick witted man came to his rescue, the famous Odysseus. In exchange for support of his own marriage, he offered the following advice: Require all of Helen’s suitors to promise to defend her marriage, regardless who the father chose. The suitors eventually, and with a certain amount of grumbling, swore the required oath.

Finally a man was decided for Helen: Menelaus. The decision was political, as Menelaus had wealth and power and was Agamemnon’s brother. Unfortunately for all, Menelaus then made a huge mistake. He had promised Aphrodite a grand sacrifice of a 100 oxen if he won Helen, a promise promptly forgot after he received his prize. Thus he incurred Aphrodite’s wrath.

Paris, however, did not forget Aphrodite, nor their agreement. He set sail for Greece under the pretense of a diplomatic mission in order to claim Helen. Before entering the palace, the goddess of beauty held up her end and ordered Eros to shoot Helen with his arrow. The moment she set her gaze on Paris, Helen was in love.

Paris didn’t think this kidnapping was really such a big deal. There were plenty of men before him who had stolen women from foreign lands without repercussion. Jason, for instance, took Medea from Colchis, and Heracles captured the Trojan princess Hesione without any issues.

This time, however, was going to be very different.

According to Homer, it didn’t go straight to war. Menelaus first journeyed to Troy to seek a more peaceful solution. When that didn’t work, Menelaus asked Agamemnon to uphold the oath that the Achaean kings and princes had sworn, to defend Helen’s marriage. Emissaries were sent to them all, to gather them in order to retrieve Helen.

Not all of them came willingly.

Odysseus, for instance, feigned madness in order to avoid the war. He tried to sow his fields with salt as proof, but Agamemnon’s man tricked him into revealing his sanity. He placed Odysseus’ infant son in front of the plough’s path, and the father could not fake delusion any more. He turned aside to save his child.

Achilles, too did not readily join forces. His mother disguised him as a woman so he would not have to go to battle. When Odysseus, Telamonian Ajax, and Achilles’ tutor Phoenix came to fetch him from the island of Skyros, they could not immediately recognise him. Fortunately, they had a plan. The men pretended to be merchants bearing trinkets and weapons. They were then able to spot Achilles out the second he chose to look at the swords and spears rather than bracelets and beads.

The Achean army was almost ready. All of the suitors sent their forces to the city of Aulis, and one by one the commanders with their ships and men arrived. The last one to show up was Achilles, who was at the time only 15 years old.

An omen then occurred. A snake slithered from a sacrificial altar to a sparrow’s nest nearby. It ate the mother and her nine babies and was then converted into stone. Troy, apparently, would fall in the tenth year of war.

And just like that, with the twisting roots embedded, the bud of the story was ready to break through the soil and bloom.

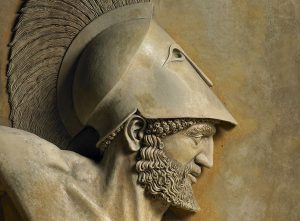

Odysseus

Odysseus

Odysseus and the Sirens

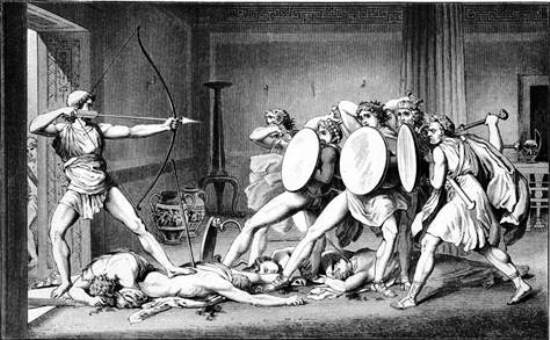

Odysseus and the Sirens Odysseus fights Penelope’s suitors

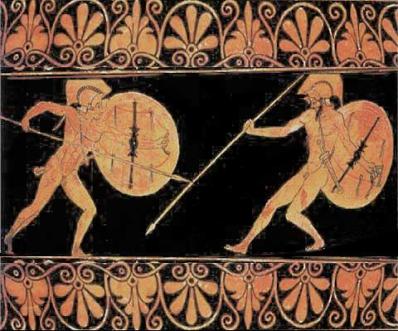

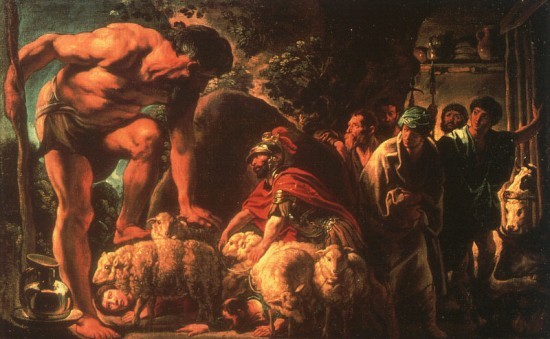

Odysseus fights Penelope’s suitors with Telamonian Ajax, king of Salamis who would throw himself on his sword whilst under the weight of public shame. He is sometimes referred as “Greater Ajax” or “Ajax the Great”. This man was considered one of the largest and most ferocious Greek warrior of

with Telamonian Ajax, king of Salamis who would throw himself on his sword whilst under the weight of public shame. He is sometimes referred as “Greater Ajax” or “Ajax the Great”. This man was considered one of the largest and most ferocious Greek warrior of  It is during the fall of Troy that Ajax encounters

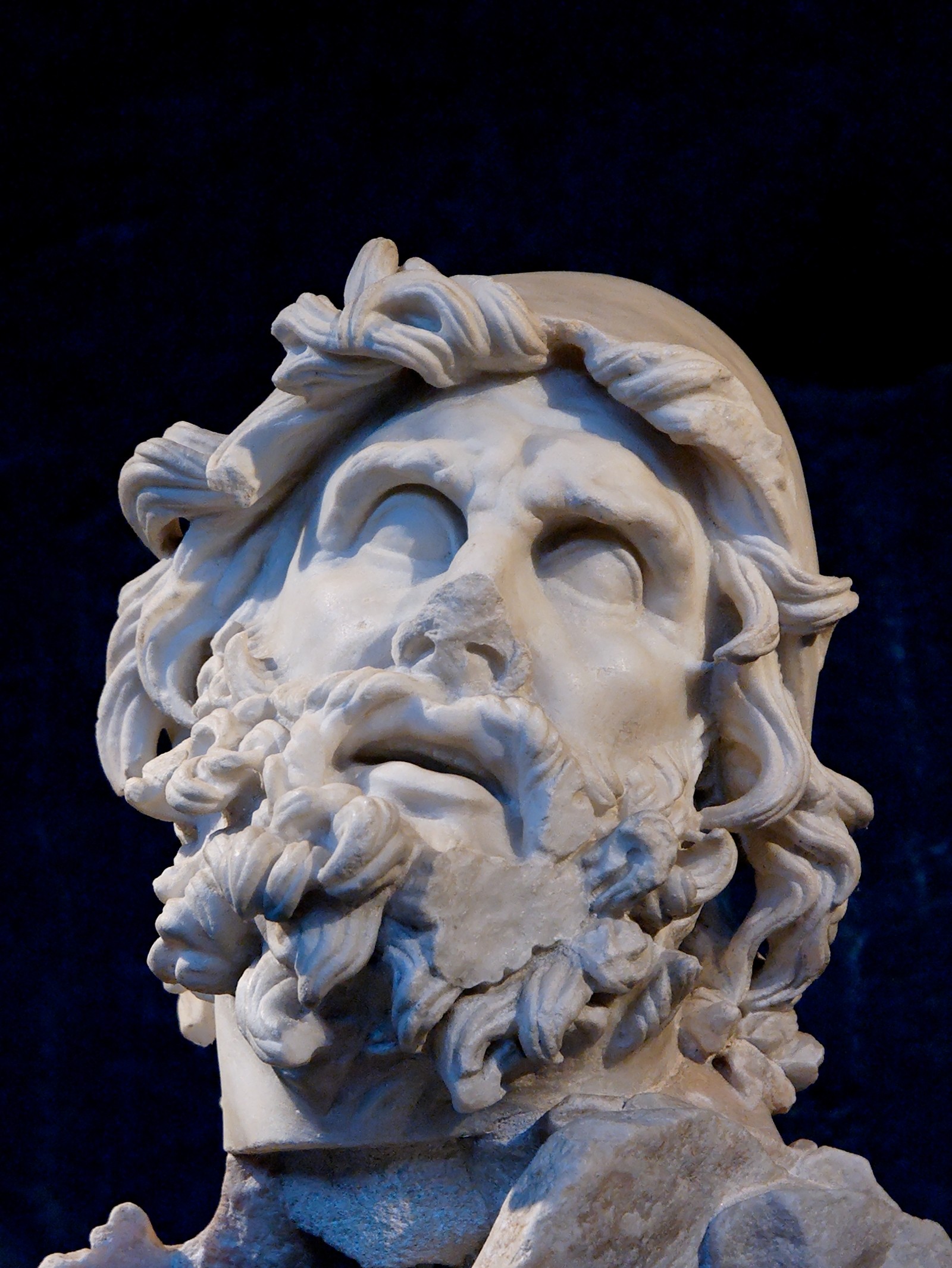

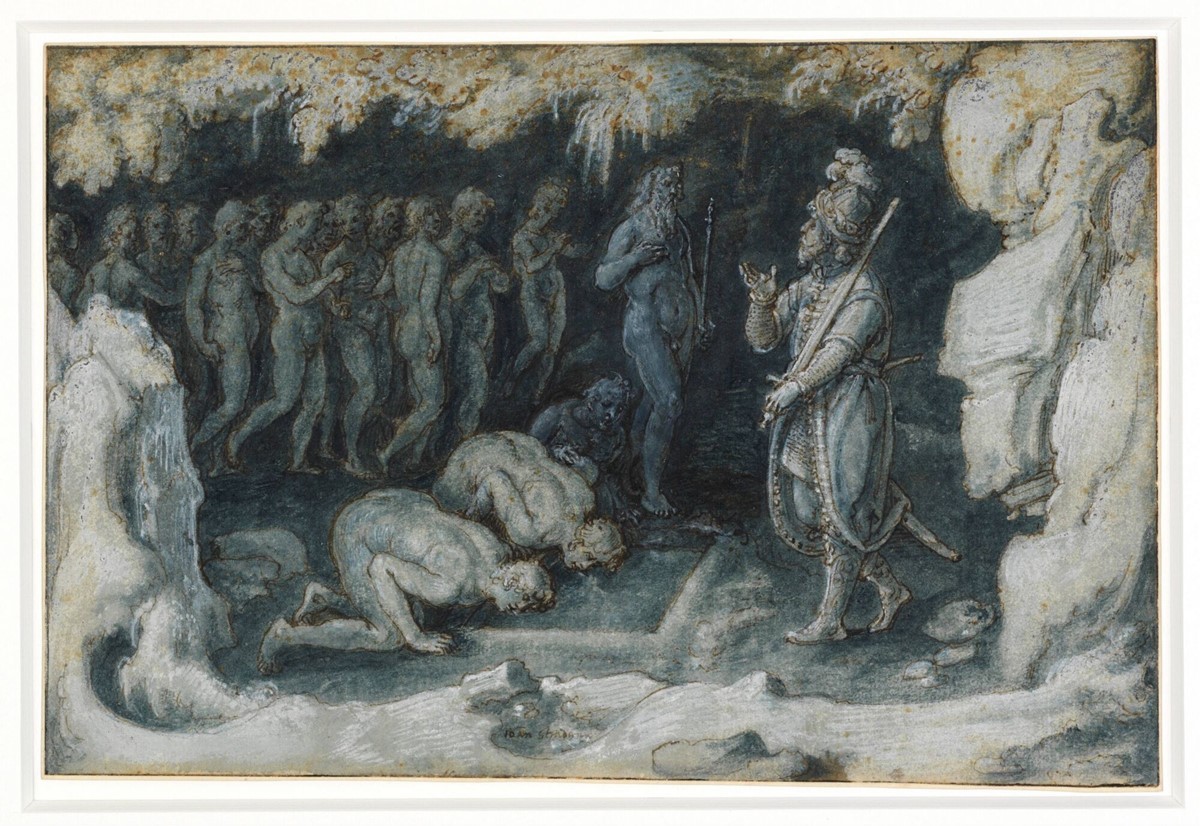

It is during the fall of Troy that Ajax encounters Poseidon hears this boastful claim and becomes enraged with the mortal clinging to the rocks. Poseidon approaches Ajax, desperately clinging to life, and strikes the rocks with his mighty trident. Ajax is cast off of the stones and drowns beneath the Aegean, a punishment for his defiance and his disrespect.

Poseidon hears this boastful claim and becomes enraged with the mortal clinging to the rocks. Poseidon approaches Ajax, desperately clinging to life, and strikes the rocks with his mighty trident. Ajax is cast off of the stones and drowns beneath the Aegean, a punishment for his defiance and his disrespect.