Flora, Goddess of Spring, and Her Festival Floralia

Written by Ed Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Many ancient civilizations had fertility goddesses that played a crucial role in their religion. Rome was no exception. Perhaps the best-known fertility goddess in ancient Italy was Flora. She was an exceedingly popular goddess and every year a major festival, the Floralia, was held in her honor.

The Goddess Flora

The name Flora ultimately derives from the Indo-European word for flower. It appears that the name Flora was a combination of ancient Latin and Oscan, a tongue native to southern Italy. There is also clear Greek influence in the development of this fertility deity. Some scholars believe that Flora’s true origin is a very ancient Italian fertility goddess.

There is some evidence that the Romans incorporated the worship of the goddess prior the foundation of the Republic. This was quite common, as the Romans tended to adopt gods and deities whom they believed would be useful.

There was a magnificent temple dedicated to Flora in the Circus Maximus, testifying to her importance and influence in the Roman world. She was regarded as one of the fourteen most important gods and goddesses and one of the few with her own flamen (priests or priestesses).

Flora was associated with vegetation and flowering plants. The Romans honored her in order to ensure her continued blessing on their lands. This was crucial for an ancient people dependent on agriculture. The goddess was worshipped throughout the Roman Republic and into the Roman Empire, until the coming of Christianity.

The Greek equivalent of Flora was Chloris. Her importance to the Romans can be seen in the many coins that bear her image. The goddess’ name has been used as the botanical term flora and is also a popular girl’s name.

Myths About Flora

There are a number of myths about Flora. Most are recorded in the work of the first-century poet Ovid, who wrote that originally the goddess was a nymph who transformed into Flora after being kissed by Zephyrus, the God of the West Wind. She was depicted as having the power to make both nature and humans more fertile.

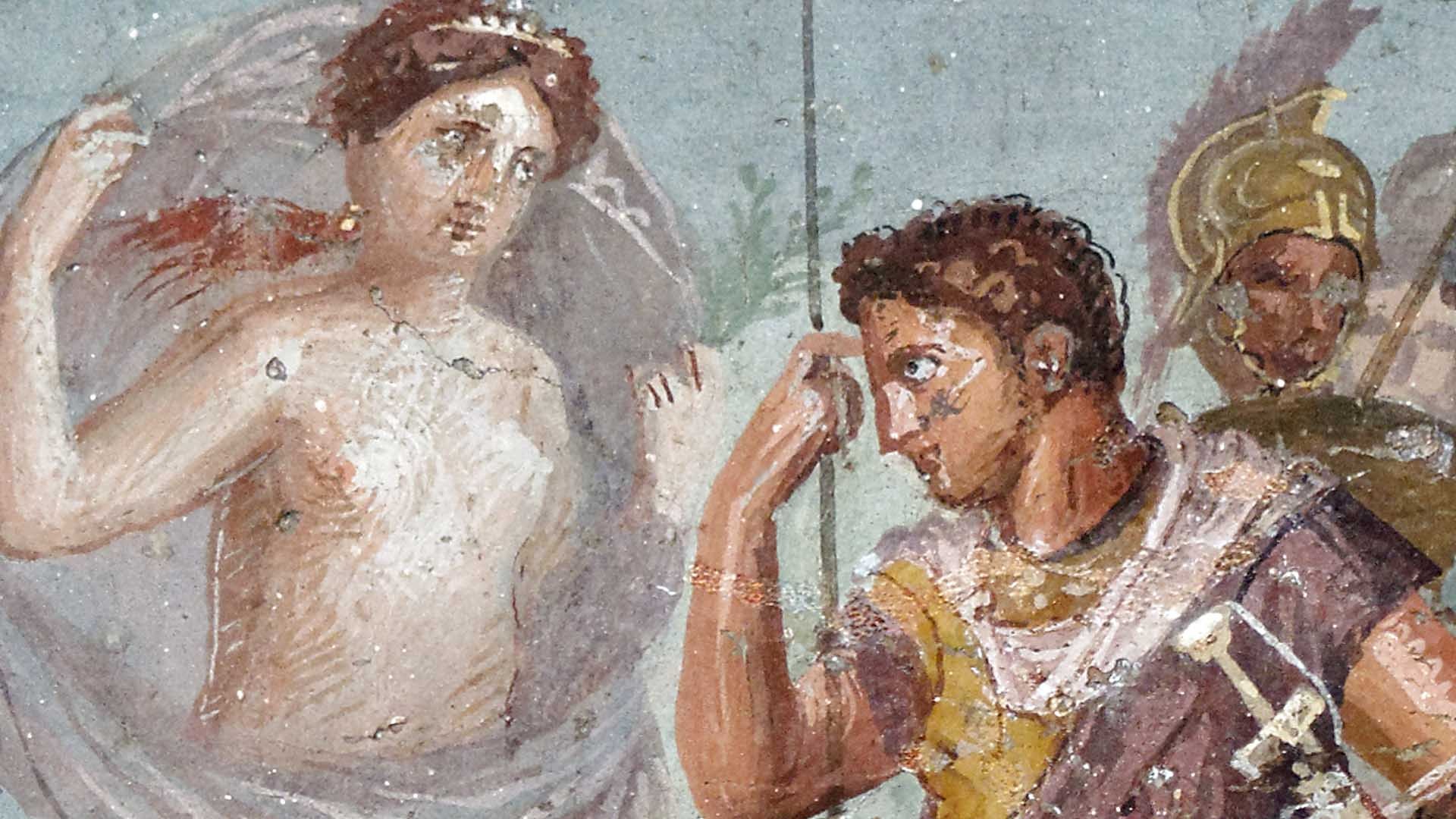

In one account, she helped Juno to become pregnant with a child in revenge for Jupiter giving birth to Minerva from his head. Flora did this with a magical plant. In some myths, the goddess Flora was associated with Aphrodite, the goddess of desire and love.

The Floralia

The festival of Floralia was established around 250 BC and soon became one of the most popular in the Roman calendar. The festival was a five-day affair that fell, in our calendar, in late April and lasted until May.

According to legend, the festival was first instituted on the advice of the Sibylline Books, which were considered prophetic. For the Romans, the festival symbolized the cycle of life, birth, and death. It honored Flora and was a time of dancing, gathering of flowers and the wearing of colorful clothes.

The festival was also an occasion to hold Public Games, which were paid for from fines levied throughout the year. These Games lasted six days. The Games and the festival were both administered by the Roman magistrate, the aedile.

Generally, the Floralia opened with theatrical performances, often mimes that could even include a naked actress. Then came the first day of the Games and at night, a ceremonial sacrifice to Flora. There were great efforts made to make the theatrical events around the festivities enjoyable and in 69 AD a tightrope-walking elephant was part of the celebrations!

The festival gained popularity, prompting Julius Caesar to proclaim the Floralia an official holiday. It is considered an important social event in ancient Roman society, as it fostered a sense of community and allowed people to enjoy themselves after the hardships of winter.

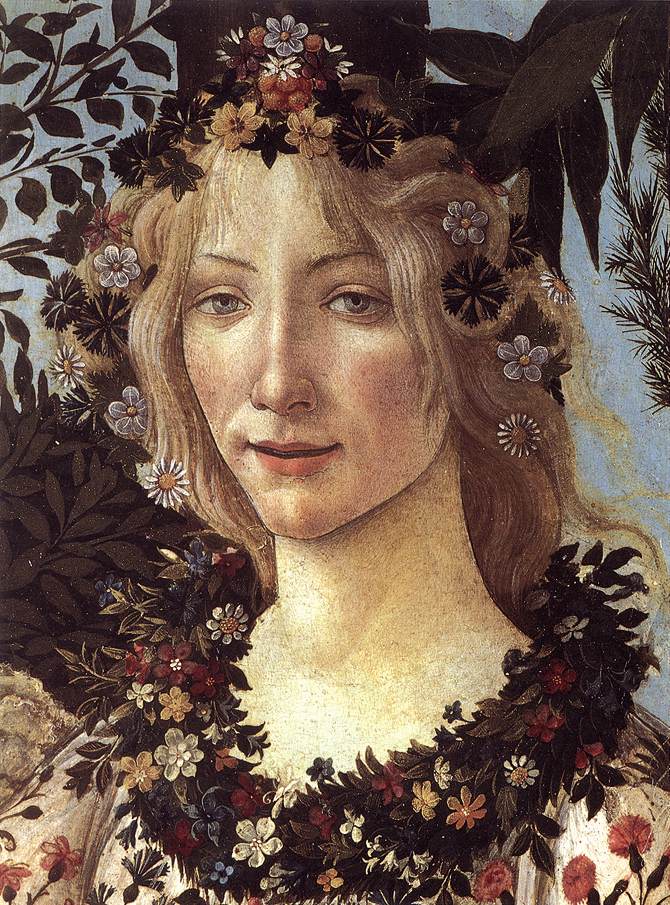

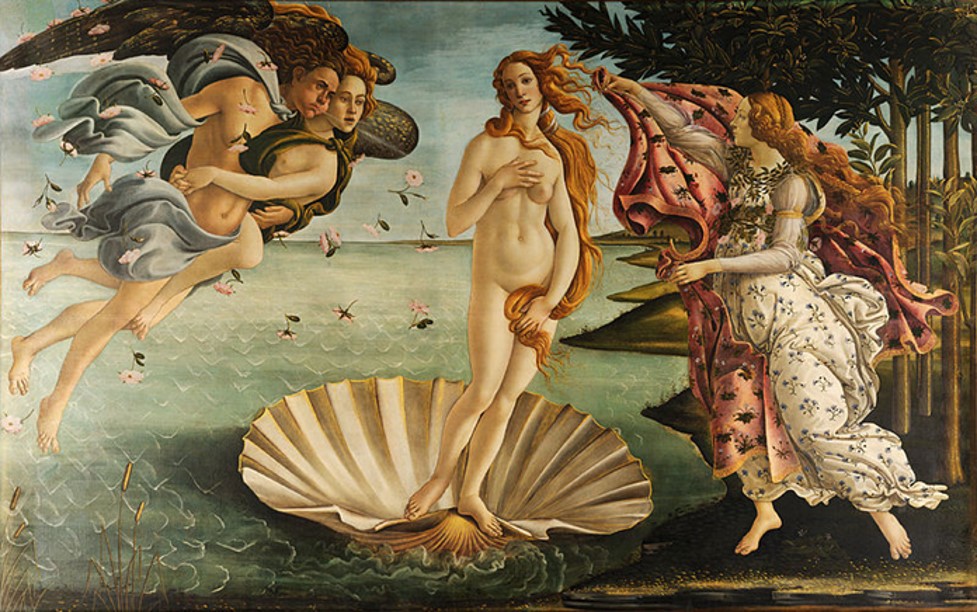

Some scholars believe that the Floralia was the inspiration for the May Day Festival, which is still popular in many Northern European countries. The goddess Flora was also reverenced by humanists in Renaissance Europe, who featured her in paintings, sculptures, and poetry.

The figure of Flora has been painted by some of the greatest painters in the Western tradition, such as Botticelli and Poussin.

Conclusion

Flora was an important Roman goddess. The worship and cult of Flora are testament to the importance of the natural life cycle for the ancient Romans. The festival of Floralia help unite ancient Roman society as they came together to celebrate the magnificent of nature and the joy of Spring through art and sport.

References:

Berrens, D., 2019. The meaning of flora. Humanistica Lovaniensia. Journal of Neo-Latin Studies, 68(1), pp.237-249.