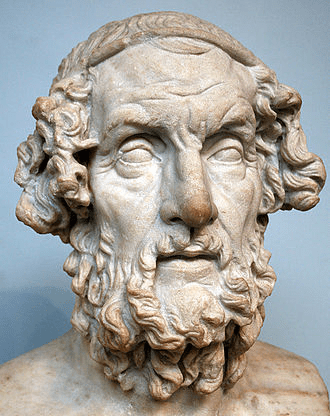

The Homeric Question: Who WAS Homer?

by Ed Whelan, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Homer is considered one of the greatest poets who ever lived. The literary and cultural influence of the Iliad and the Odyssey is incomparable. But who was Homer, exactly? The answer is a little bit complicated…

You see, for many centuries scholars have questioned not just the identity, but even the existence of Homer. The ‘Homeric Question’ seeks to understand if Homer actually wrote the works attributed to him, and if not, then who?

The Life of Homer

We’ll get to the more modern scholarship in a moment. But first, who did the ancients think Homer was?

Well, in antiquity, Homer was believed to have composed his great works in the Greek Dark Ages (9-8th century). According to this tradition, he was born on the island of Chios and was blind from birth. It was believed that he was a wandering bard, and that he sung his epics to the public at festivals. These poems were based on events and heroes from the Mycenaean Age (12th-11th century BC). His works were later written down, and though they had been changed and edited, it was still believed that the Iliad and Odyssey were ultimately the product of one mind: Homer’s. Even as far back as antiquity, however, there were those who questioned if Homer really did write the epics…

The Homeric Question

Now we’re going to jump forward in time quite a bit. Just a couple of millennia!

Beginning in the 17th century, scholars began to develop textual criticism. Figures such as Isaac Causbon analysed the texts of Homer and found certain discrepancies. Critics began to suspect that the works of Homer were not actually written by just one person.

Rather, they believed that ‘Homer’ was the name given to a much larger oral tradition of storytelling. The reading public rejected this idea right down to the 19th century, and maintained that the figure of Homer, the blind bard, was the author of the works.

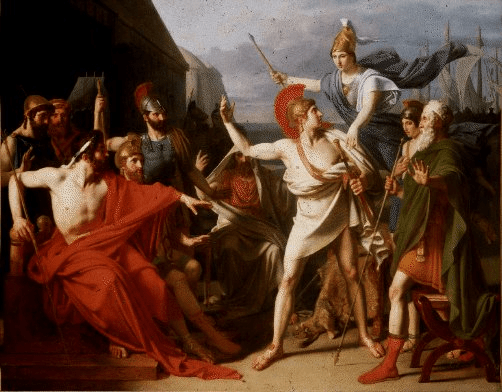

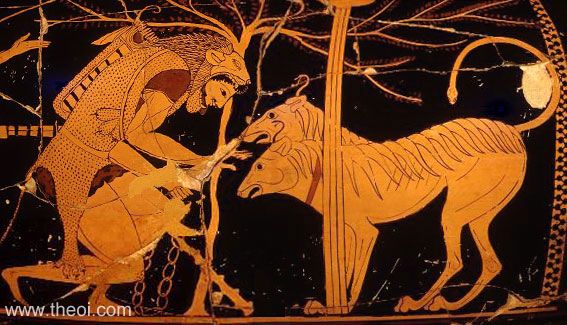

Milman Parry (1902 – 1935), an American Classicist, later revolutionized the study of Homer. You see, across the Iliad and the Odyssey, there are many formulaic expressions, such as the epithets ‘divine Odysseus’ and ‘swift-footed Achilles’. Parry showed that there was a reason for this consistent repetition. Their presence was no accident: they were in fact memory devices, which allowed the reciting bard to improvise during his public recitations. Parry was also influenced by the recordings of bards from the Balkans, who similarly used formulas to recite very long epic poems. Parry argued that the works of Homer were part of a long literary tradition. He and later scholars proved that “Homer” (as he was commonly understood) did not write the Iliad and Odyssey. Rather, they emerged from a very ancient tradition.

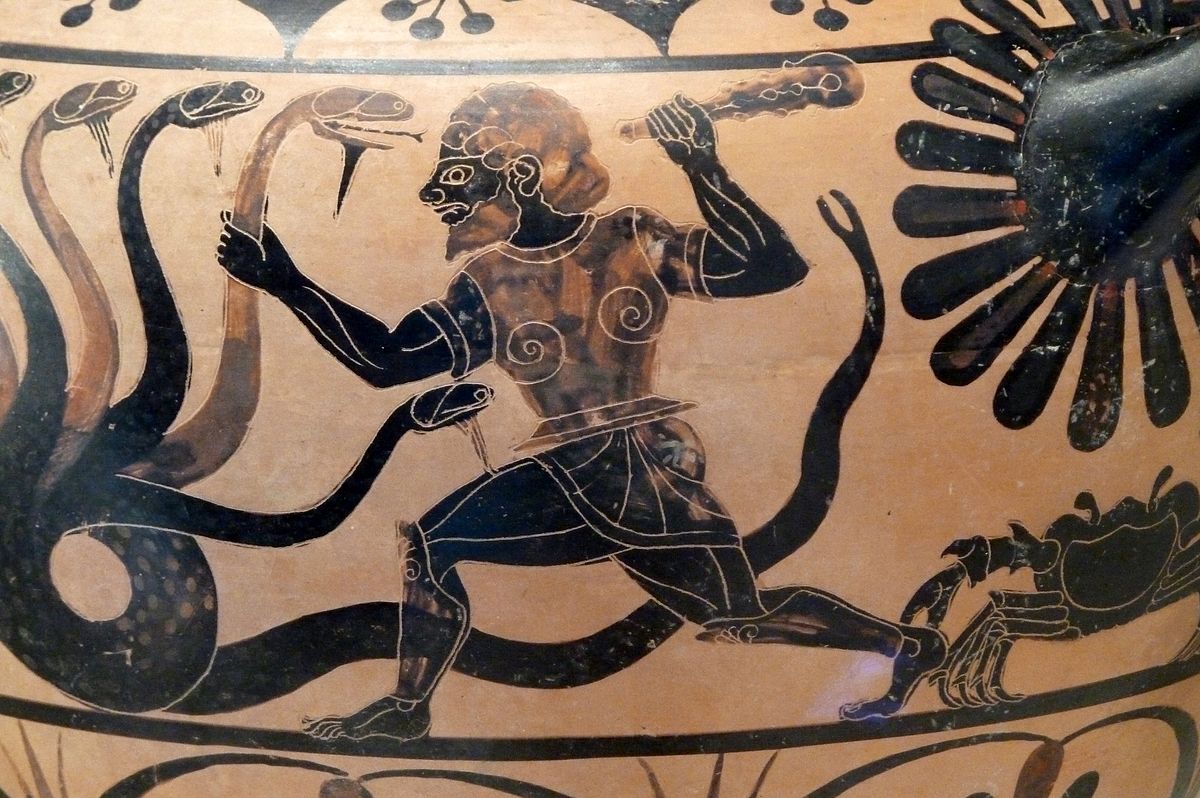

Based on archaeological finds, later scholars have found that the Homeric works displayed a knowledge of Mycenaean warfare and weaponry, which indicates that this oral tradition dated back to the 12th and 11 century BC. Some elements of the poems, however, also came from later time periods. This confirmed that the epics evolved as part of a very dynamic oral tradition; the Homeric Question was resolved. The most famous epics in all of literature were not written by one man named Homer. It was, in fact, the creation of many minds.

So Who DID Write the Iliad and Odyssey?

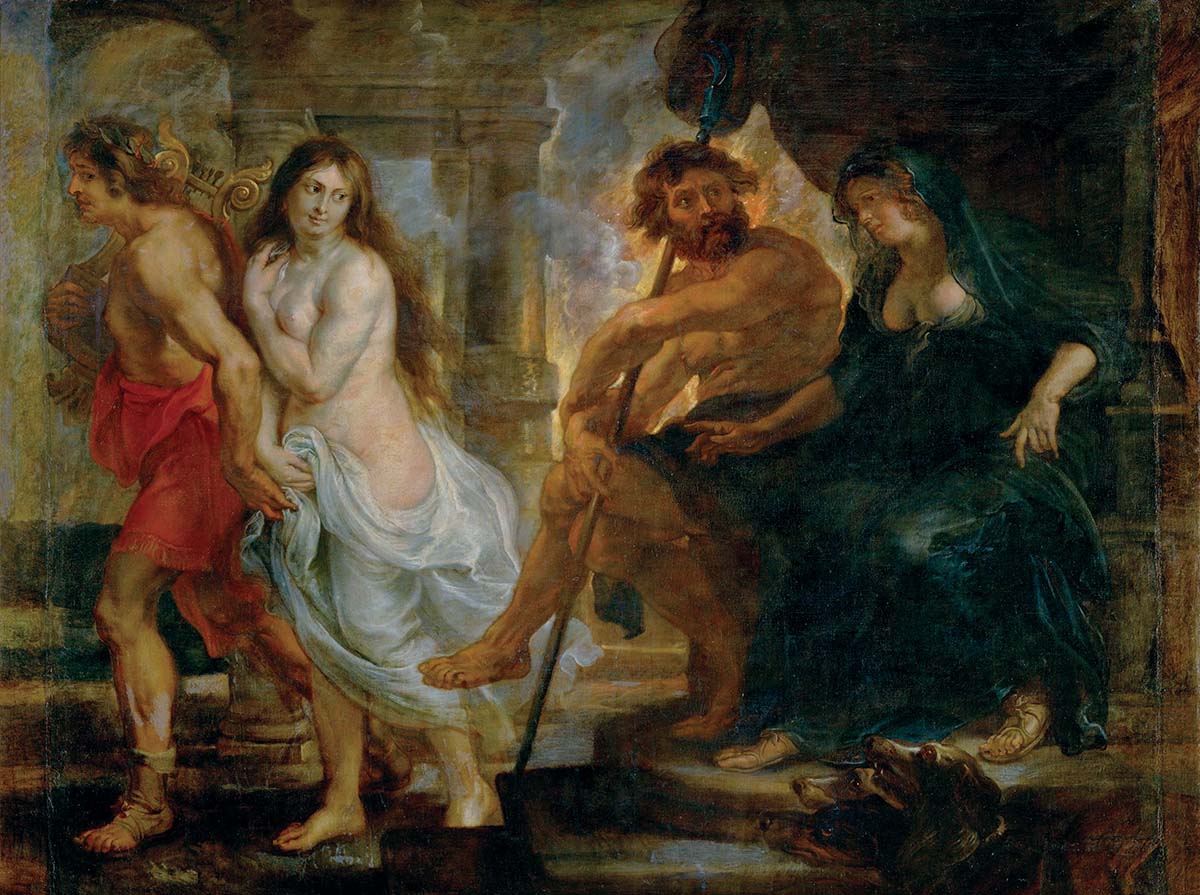

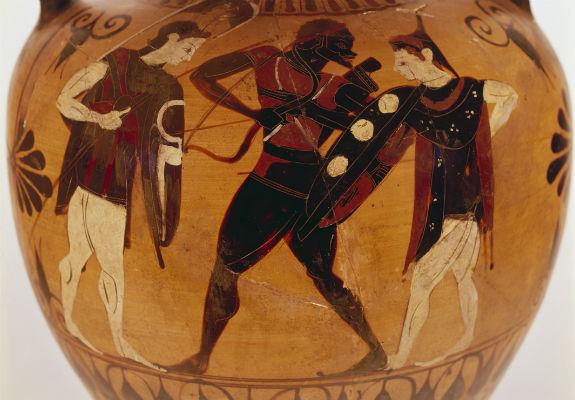

It seems likely that itinerant bards sang of the heroics of the Greeks during the Trojan War during the Late Bronze Age. These were the instigators of the Homeric epics. Later bards developed their works and added to them. Scholars speculate that “Homer” may have been a name for groups of travelling bards who travelled the Greek world. The stories told about Homer may reflect the fact that the bards had connections to the island of Chios. Yet mysteries still persist: there is no agreement on this particular theory.

The Homeric tradition was then popularized by the rhapsodists who succeeded the traditional bards. These were professional singers who performed the works of others, and would have performed the poems attributed to Homer. It is possible that Homer was a famous rhapsodist, and the epics were mistakenly attributed to him. It’s also possible that the popular image of Homer as the blind bard was simply a creation of a similar oral tradition. All of these bards and rhapsodes contributed to the development of the Homeric works and helped to make them such great works of art.

It appears that the oral poems were written down sometime in the 8th century after the development of the Greek alphabet. The various Homeric poems were compiled in Athens during the rule of the tyrant Peisistratus (c 520-540 BC), according to one source. Another tradition argues that the versions of the work that we have were the result of scholars who worked in the Library of Alexandria (c 2nd century BC).

Conclusion

The Homeric Question has been largely solved. There was no single genius behind the works. The epics set during the Trojan War and its aftermath were the product of a very ancient tradition that dated back to the Bronze Age. This tradition was constantly evolving. Bards, rhapsodists, and scholars all contributed to the work in some small way.

References

Burgess, Jonathan S. (2003). The Tradition of the Trojan War in Homer and the Epic Cycle. JHU Press