By Ben Potter

Polybius was born 200 BC in Megaopolis, Arcadia. A town both geographically and politically at the heart of the Peloponnese, from where it seemed Polybius was destined for a lifetime of political greatness.

After being given the honor of publicly bearing the skilled Greek general and statesman, Philopoemen’s ashes in 182 BC, he was made envoy to Alexandria two years later and in 170/69 BC he served in the military as hipparch, or ‘the leader of the horse’.

However, this was (within the Confederacy) as good as it got for Polybius.

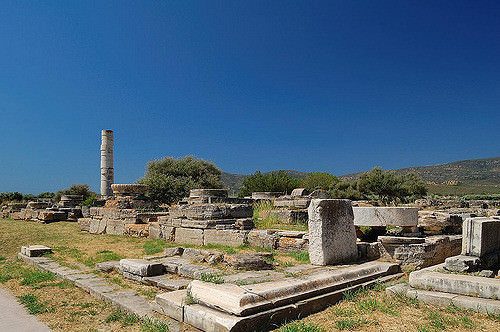

Megaopolis, Arcadia

In 168 BC after the decisive battle of Pydna, the once-proud Macedonian Empire was reduced to a Roman client-kingdom.

Callicrates, the new leader of the Achaeans, was a man who knew on which side his bread was buttered. He agreed to send to Rome 1000 political hostages, people who had unsympathetic views towards the Latin powerhouse, people… like Polybius.

He was sent to Rome a hostage.

He was sent to Rome in chains?

Well… this is the key distinction – Polybius was not, like so many of the hundreds of thousands of Greek prisoners before him, a slave, but a hostage. And a hostage, unlike countless other captives tucked away in the nooks and crannies of Italy, who was lucky enough to be sent to Rome.

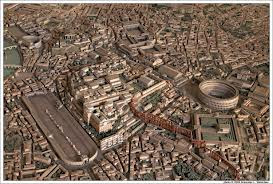

Reconstruction of Ancient Rome

He was sent to the centre of power, to the budding young capital of the new world where an educated man with a capacious mind and a thirst for knowledge would be recognised, not for his history of Roman antagonism, but for his great potential.

After all, at one point on its arc of dominance, every superpower is the land of opportunity.

So Polybius became a prominent and respected person (his skill in horse-riding and hunting are said to have endeared him to many). He had the appearance of possessing civic rights (and in reality he enjoyed some extra-civic privileges), but he was not permitted true freedom. He was de facto under house arrest within the city and not allowed to venture out except temporarily and under supervision.

However, it appeared he had no real desire to stray from his captors. This leads us to the point of how ‘Greek’ Polybius really was, because from the day of his captivity, he was in all but name, a Roman.

He was much like Christopher Hitchens – a new talent from the old world.

Polybius was not merely a heavyweight dinosaur. He rejected the old world in favor of the new; was seduced by a constitution, an organization, an unstoppable drive from the corridors of power.

He was ideally and uniquely placed to chronicle, in his own words, how “almost the whole of the known world was conquered and fell under the single rule of the Romans in a space of not quite 53 years”.

However, this was not his day job. He was also the mentor to Scipio Aemilianus, the grandson of Scipio Africanus – the scourge of Hannibal.

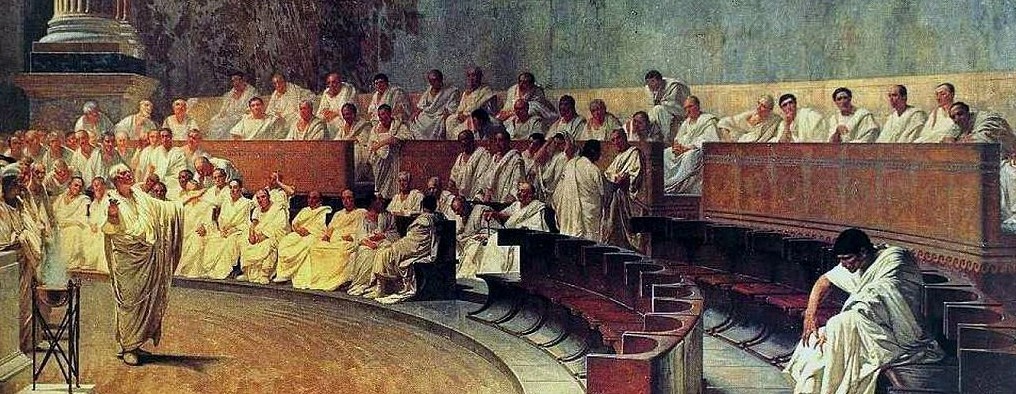

Scipio Aemilianus

In such a capacity, Polybius travelled with the aristocratic young soldier all over the empire, witnessing first-hand just how the Romans got things done.

He was impressed… really impressed.

The irony would not have alluded Polybius that he was originally exiled to Rome because of his sufficiently unsympathetic stance vis-à-vis the thundering juggernaut, only then to become the great Roman apologist for a state which became his sanctuary, his home and his happiness.

His travels with Scipio continued to Spain and Africa in 151 BC and it was on this jaunt he supposedly retraced Hannibal’s steps by returning to Italy over the Alps!

Shortly after this, in 150 BC, the Achaean hostages, of which Polybius was originally a part, were released, but Polybius opted to remain in Rome with his friend and protégée, Scipio. On his journeys, Polybius witnessed firsthand Scipio’s destruction of Carthage, the sacking of Corinth, and the ‘settling’ of Greece after the ‘liberation’.

A more active or dynamic life for an historian is hard to imagine. Thus it seems fitting that he died, not through idleness, but after a throw from his horse at the age of 82.

He is survived by his magnum opus: his Histories.

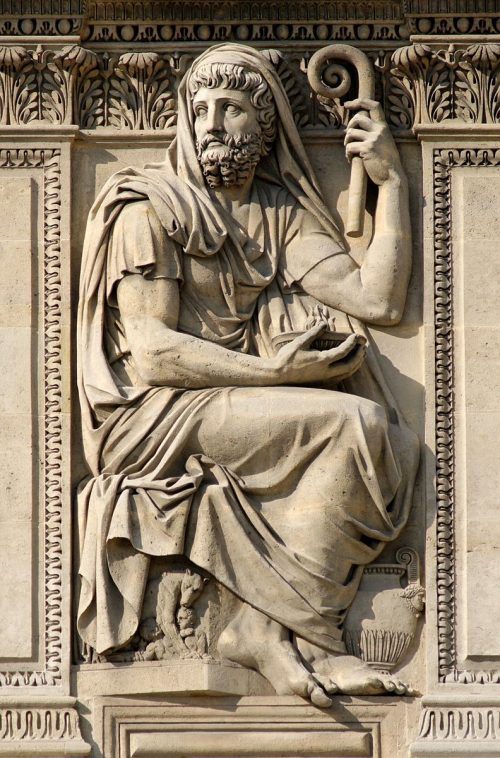

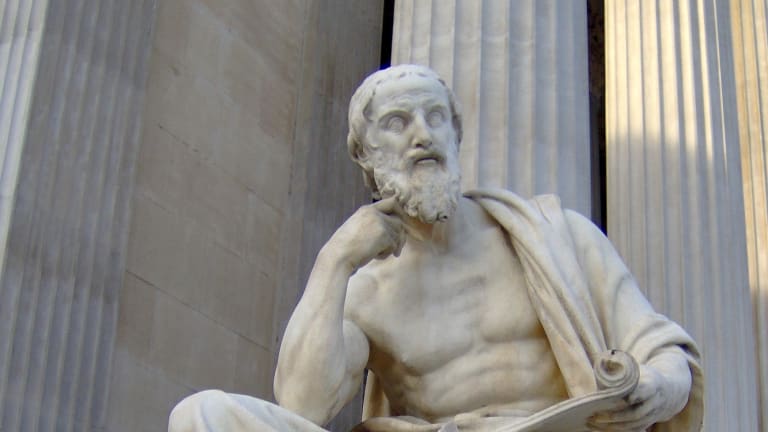

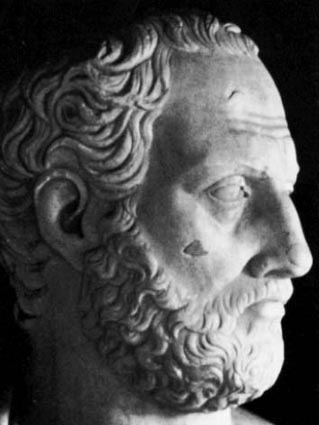

Statue of Polybius

Though only books one to five of the original 40 survive intact, they are of such importance and quality that they sing through the ages without an echo of distortion.

Polybius told history in a far less higgledy-piggledy fashion than had been done before. In fact he was the first ancient historian who can be held up to modern standards of historiography; not rambling like Herodotus or slapdash like Thucydides.

He chronicled by Olympiads (4 yearly cycles), conveniently breaking them down into quarters and cross-referencing these by territories (reading from the North and West). A sensible and obvious way of organizing a history? Well… yes it is now, thanks to Polybius.

He studied documents and other written texts, being one of the first to prioritize them as a key component to fully understanding historical events. He also recognized the value in talking with veterans and any other source who was as close to the action as was possible.

He thought a historian should explain rather than merely describe – he didn’t want to merely present the facts, but discuss their significance:

“The mere statement of a fact may interest us, but it is when the reason is added that the study of history becomes fruitful: it is the mental transference of similar circumstances to our own that gives us the means of forming presentiments about what is going to happen”.

And although he was not neutral, he was honest – sometimes brutally so. He wore his heart on his sleeve and was happy to justify what he considered to be correct.

However, leaving style and method aside, why all the vehement pro-Roman sentiment from a man imprisoned for the exact opposite?

Polybius was a Roman hostage, but he was writing for Greeks. Greeks whose sovereignty was being eroded by Roman imperialism. Was he trying to get them to swallow what was inevitable – Roman domination? Did he believe it was actually for the best? Or was he a mere pragmatist?

He would surely have viewed Rome as magnificent and frightening, perhaps even an unstoppable, force.

Polybius had known a Macedonia which had dominated Greece for over two centuries. To him, Macedonian power must have seemed an absolute, a constant which could at best be resisted, rued or run from, but could never be stifled, stripped and certainly never stopped.

Therefore any force which could unfetter Greece from Macedon must have been such a mighty superpower that it could only continue to dominate throughout the ages.

Polybius believed the Roman behemoth achieved its success via its constitution (his writing on the subject greatly influenced John Adams). However, he didn’t foresee that it would fail to evolve with the demands of the empire and would effectively be no longer fit for purpose by the time Julius Caesar and then Augustus decided to respectively circumvent and then dismantle it with relative ease.

In the 2nd century BC, western superpowers were in their infancy, thus Polybius didn’t have that luxury we do – the ability to look back upon two millennia of growth, stagnation, decay and failure of the greatest (or, if you prefer, most terrible) nations on Earth.

So, although the Roman rocket was still rising, and although he covered its trajectory with great vim and gusto, Polybius had no idea that his captors-turned-hosts had taken their first step towards losing a great empire… they had established one.

Anything from international affairs to the tenuous state of the global market, they got it all in healthy doses.

Anything from international affairs to the tenuous state of the global market, they got it all in healthy doses.

The world view of political realists like Thucydides casts a rather bleak picture of human nature and the patterns of world affairs. The Greeks were cast into war much the same way the Romans were time and time again as their empire expanded. The American government of the 50’s and 60’s watched the rise of communism and the expansion of the Soviet Union with dread and concern. And again, we were cast into war.

The world view of political realists like Thucydides casts a rather bleak picture of human nature and the patterns of world affairs. The Greeks were cast into war much the same way the Romans were time and time again as their empire expanded. The American government of the 50’s and 60’s watched the rise of communism and the expansion of the Soviet Union with dread and concern. And again, we were cast into war.