Viewed as a whole, Politics is a rather intimidating piece of work. No mere political treatise, it is an examination of the origin of society, the meaning of political justice, the fundamental elements of the state, and the responsibilities of the ruling class to the citizens and vice versa.

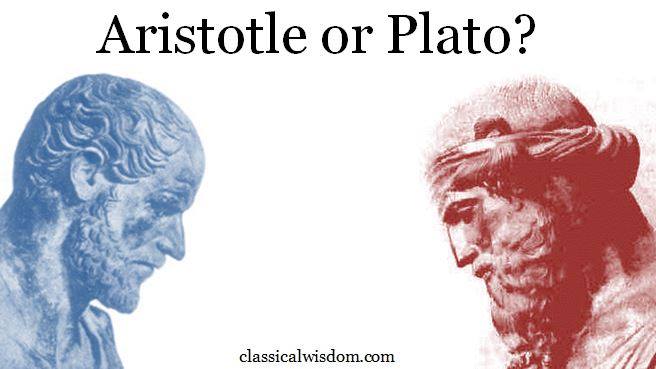

Politics, when you get right down to it, aims at uncovering “the ideal state”. The more astute of you may already have realized that this was also, more or less, the goal of Plato’s magnum opus, The Republic.

However, while Plato devoted much of his time in Republic to establishing the credibility of an unseen realm of forms, Aristotle instead focuses on that which is empirical, observable, and makes use of the numerous forms of political systems that were practiced during the age, discussing their strengths while uncovering their blunders.

Aristotle and Plato both attempted to define the “ideal republic”. However, they each came to dramatically different conclusions.

The result is a piece of philosophical literature that does occasionally focus on the theoretical and the hypothetical, but also gives us practical and applicable advice when it comes to living in a political society.

As it turns out, there are a number of lessons found within Politics that we might do well to listen to. For instance, did you know that…

The Importance of Private Property and Self-interestedness

The first lesson comes to us when Aristotle actually critiques the ideas that his mentor laid out in Republic. For in Plato’s work, the philosopher argues that the state should be happiest if the citizens are as unified as possible.

Plato makes the claim, somewhat capriciously, that all the wives of the rulers ought to be shared. Additionally, fathers ought not to think of a child as being their own son or daughter. Rather, the citizens should view all children of the state as being their own.

Taken literally, and Aristotle sees no other way to take it, this sort of thinking would effectively eliminate private property and would revert all things in the state, including women and children, to shared ownership.

But shared ownership simply is not the way to go, Aristotle tells us. The sharing of property and children will make the friendship in the city “watery”. It is human nature that when responsibility (the responsibility of raising child for instance) is divided among many (the entire state) the result is that nobody truly pays any attention to the responsibilities at hand.

Aristotle insists that private property is essential to the wellbeing of the state.

Everybody simply assumes that somebody else will care for these matters and the people become lax, uninterested in managing any affairs. Aristotle compares this to a dinner party that runs more smoothly when there are a few servants attending to their own affairs rather than numerous servants attempting to tend to the entirety of the responsibilities.

The benefits of having private property are similar. For people are most interested in tending to and facilitating that which belongs to them or that which might benefit them. If all property is shared, there is no incentive for the citizens to maintain or develop the lands and properties of the society.

Self-interest, Aristotle tells us, is human nature. The philosopher writes as much in Nicomachean Ethics when he declares that the goal of a human life is to achieve our individual happiness through an understanding and application of virtue.

And so we see that the ownership of private property, as well as the self-interestedness of the citizens, is actually beneficial to the state as a whole.

“Evidently, then, it is better if we own possesions privately but make them common by our use of them…Further, it is unbelievably more pleasant to regard something as one’s own. For each persons love of himself is not pointless, but a natural tendency.” –Aristotle (Politics, Book II)

Aristotle and the Middle Class

It is not uncommon for Aristotle to apply the lessons of virtue pertaining to the individual to the lessons of virtue within civic life. It is not coincidence that Politics follows Nicomachean Ethics. Once Aristotle has established happiness, virtue, pleasure, etc. for the individual, it is only natural that these same lessons be applied to the polis as a whole.

Aristotle describes virtue as being a mean, a balance, between two extreme characteristics. Courage, for instance, is a balance between the extremes of cowardice and recklessness. Generosity, similarly, is a balance between the extremes of miserliness and over-generousness (giving away all of your money and possessions).

The philosopher tells us that it is unavoidable to have within a society those who are overly prosperous and those who are overly disadvantaged. It is unfavorable for the state to allow either of these parties to rule. The prosperous, because of their good fortune and lavish upbringing, are not willing to be ruled. The needy, being overly abased, do not know how to rule or do not posses the resources to enable themselves to learn to rule.

Aristotle claims that these two factions, if allowed to rule, would destroy the justice of the polis. The prosperous, having no empathy for the poor, would rule over the citizens as a master

Essentially, Aristotle becomes one of the oldest advocates for a strong middle class.

might rule over a slave. This would appear common in an oligarchy. The poor, despising the rich, would enact laws to seize the property of the prosperous and in doing so, commit a grave injustice and damage the friendship within the state. This, it would seem, is common among “majority rule” democracies.

The compromise is that there must be an “intermediate class of people”. These intermediate people, embodying a balance between two extremes, would be able to appreciate the value of hard work, of earning a wage, while still having enough resources to educate themselves and learn the ways of virtue so that they might one day be just rulers.

Essentially, Aristotle becomes one of the oldest advocates for a strong middle class.

This middle class, ideally, should outnumber the combined numbers of both the prosperous and the needy. This strong middle class is the backbone of the society, providing just and compassionate rulers while counteracting the polarizing effects of the needy and the overly prosperous.

“Clearly, then, the political community that is in the hands of the intermediate people is best and the cities capable of having a good system are those in which the intermediate part is numerous and superior…” –Aristotle (Politics, Book IV)

We Must Avoid Political Extremes

In keeping with the idea of finding an intermediate between two extremes, Aristotle warns us of the dangers posed by political extremes. We mentioned previously that self-interestedness was beneficial to a society. An excess of self-interest, however, leads to selfishness and propagates ideas that are harmful to the citizens and the polis as a whole.

The partisan citizens within a society must not be allowed to achieve political relevance. For they assume that that which is of interest to them is the only interest, and therefore demand it in excess.

The consequence is that laws that are overly democratic or overly oligarchic will be enacted. Aristotle gives, again, the example of equality of property that is often enacted when the needy citizens gain too much influence within a state.

The overly prosperous, if allowed to rule, will enact laws that degrade the poor, laws that do not allow the needy to improve their station in life.

While both parties believe that these policies are just, for they are indeed in their best interest, such laws breed discontent and hatred among the citizens, damaging the concord of a society.

Aristotle compares the degradation of the state at the hands of the political extremists to the deformation found on a body part. A nose, Aristotle tells us, might have certain imperfections. It might be hooked or snubbed, but it is, unmistakably, still a nose. However, when the nose deviates further it will first lose its proper proportion. If it continues to deviate, the nose, or any body part, will be unrecognizable.

Similarly, political systems are never perfect. However, if we allow them to be held hostage by political radicals, the political system will diverge so far that it will become something unnatural.

“…an oligarchy or a democracy may be in good enough condition even though it has lapsed form its best order; but if someone takes either system to further extremes, he will make the political system worse and finally make it cease to be a political system at all.” –Aristotle (Politics, Book V)

Education Must Support the Political System

This final tidbit from Aristotle can be found in Book V of Politics. Even though it is only a few paragraphs long, I have always believed that this passage was of supreme importance.

Why?

Because most people believe that philosophy and “the real world” never overlap. They are mutually exclusive. Philosophy goes one way and reality goes the other, and never the twain shall meet!

The philosopher claims that, in order for the political system to survive, we must educate ourselves and our children in the aims and ideals of the political system.

But Aristotle gives clear evidence that such thinking is incorrect. The philosopher claims that, in order for the political system to survive, we must educate ourselves and our children in the aims and ideals of the political system. A government cannot long stand if the citizens are ignorant of the principles of a society.

What, for instance, are the aims and ideals of a democracy? Is it a system that aims at egalitarianism? Personal freedom? Majority rule? We must answer these questions adequately if we wish for our society to long endure.

Aristotle states that two features, at least during the age of classical Greece, define a democracy: control by the majority and freedom.

But what do we mean by “freedom”? Does possessing democratic freedom mean that we are able to do whatever we please, to live however we wish? Is this the goal of a democratic society?

Aristotle rejects this. Such a society would never survive.

A political system should aim at fulfilling the needs of the many while still protecting the individual and creating an environment that facilitates the growth of virtue. Remember, an active expression of virtue is the highest good for a human life. And the state must be the medium through which this virtue is established.

Education then must fit the ideals of the political system. This is not only suggested, it is necessary for the continued survival of the state.

“…we ought to think that living in the way that fits the political system is not slavery, but preservation.” –Aristotle (Politics Book V)

The philosopher claims that, in order for the political system to survive, we must educate ourselves and our children in the aims and ideals of the political system.

The philosopher claims that, in order for the political system to survive, we must educate ourselves and our children in the aims and ideals of the political system. While friendship is indeed important, there are so many questions about friendship that we must answer. What types of people make good friends? Is it true that similars attract, hence the phrase ‘birds of a feather’? Or are similar people like “the proverbial potters” who always quarrel with one another?

While friendship is indeed important, there are so many questions about friendship that we must answer. What types of people make good friends? Is it true that similars attract, hence the phrase ‘birds of a feather’? Or are similar people like “the proverbial potters” who always quarrel with one another? So is there a way to attain real, enduring friendship? Are we doomed to live with false friends who only love us so long as we are useful to them?

So is there a way to attain real, enduring friendship? Are we doomed to live with false friends who only love us so long as we are useful to them?  If you ever want to see me get slightly annoyed, discuss ethical philosophy with me and make a case for absolute ethical relativism. If you want to see me get outright angry and attempt to strangle you, justify your position with the statement “Well, that’s just my opinion”.

If you ever want to see me get slightly annoyed, discuss ethical philosophy with me and make a case for absolute ethical relativism. If you want to see me get outright angry and attempt to strangle you, justify your position with the statement “Well, that’s just my opinion”.

“The customs of former times might be said to be too simple and barbaric. For Greeks used to go around armed with swords; and they used to buy wives from one another; and there are surely other ancient customs that are extremely stupid.” -Aristotle (Politics)

“The customs of former times might be said to be too simple and barbaric. For Greeks used to go around armed with swords; and they used to buy wives from one another; and there are surely other ancient customs that are extremely stupid.” -Aristotle (Politics)

The ethical relativist is correct, however, on one small point. There exists many customs across many different cultures. And while they vary greatly, there is no doubting that these customs all partake of the same virtues, whether it be bravery, justice, or hospitality.

The ethical relativist is correct, however, on one small point. There exists many customs across many different cultures. And while they vary greatly, there is no doubting that these customs all partake of the same virtues, whether it be bravery, justice, or hospitality.