By Van Bryan

So, that’s probably a strange thing to say, right?

After all, the popular opinion today is that you shouldn’t change for love and that your spouse shouldn’t make you change. I am who I am and that’s all that I am!

That certainly seems to be the mindset these days; at least that’s what my single friends tell me. They spend their evenings swiping left on their smart phones and making connections with total strangers on Tinder or J-swipe or…whatever.

“Never change for love.” That’s the battle cry.

Besides, if you just be yourself, surely you will find somebody just like you and you will inevitably fall in love.

Right?

“Wrong!” says Plato.

The problem with never changing who you are for love, or never letting your spouse change who you are, is that who you are might very well be a terrible person. What if who you are is an inconsiderate sociopath? Or worse, what if you are a sophist?

What I’m trying to say is that maybe a bit of change wouldn’t be so bad. Perhaps we really should let our lovers change us. Who knows? Maybe they will make us better.

That seems to be Plato’s line of thought at least. Our particular topic of interest comes from Plato’s Symposium, that unique piece of philosophical literature that asks the question: “What’s love?”

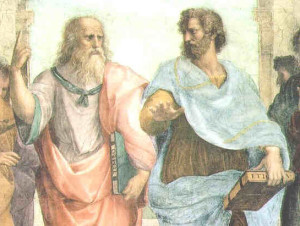

Plato is a giant in the field of philosophy. He was easily one of the most, if not the most, influential philosopher in the Western tradition. His Symposium, for those of you who don’t already know, sounds more like the setup for a particularly funny joke than an actual piece of philosophical literature.

“Okay, okay, so a philosopher, a comic playwright, and a politician walk into a bar…”

See what I mean?

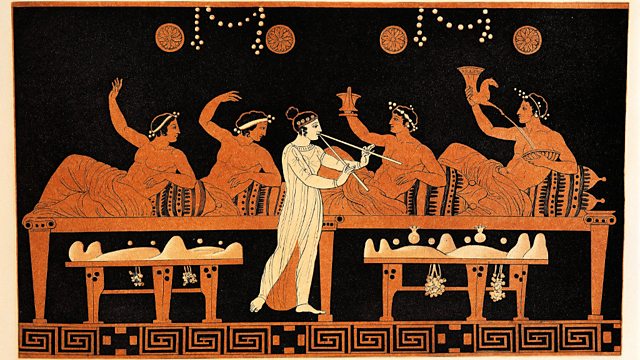

A symposium was like a dinner party in the days of ancient Greece. Except, instead of casually drinking beer and playing charades, the participants of a symposium would get rip-roaringly drunk off of wine and then commence to discuss some central topic of philosophical interest; although, that does sound pretty fun too.

Plato’s Symposium, by Anselm Feuerbach

In Plato’s Symposium, Socrates, Plato’s teacher and the man dubbed “the Father of Western Philosophy”, is joined by a handful of important Athenian figures of the age, the most notable of which are the general Alcibiades and the comic playwright Aristophanes. They all gather to discuss the topic of love.

For the more initiated of you, you will recall that there are no shortage of interesting ideas to discuss in Symposium. However, today we are looking at the speech of Pausanias and the assertion that we ought to let our lover change us.

Pausanias first notes that love is the only thing that can justify some questionable behavior. Under normal circumstances, we might look strangely at a man who lies all night on a front porch. However, when we learn that this man is doing this in pursuit of his lover, then his behavior not only becomes somewhat acceptable, but even admirable.

“And in the pursuit of his love the custom of mankind allows him to do many strange things, which philosophy would bitterly censure if they were done from any motive of interest or wish for office or power. He may pray, and entreat, an supplicate, and swear, and lie on a mat at the door, and endure a slavery worse than that of any slave…” –Plato (Symposium)

Heck, Pausanias tells us that even the gods will forgive you if you commit some transgression whilst in pursuit of your love, and we all know how unforgiving those gods can be.

So love seems to be something of great power and importance. However, Pausanias tells us that, just like anything, there can be good and bad love.

It all comes down to your motivations. Why do you love somebody? It may very well be that you love somebody because they are beautiful or wealthy. This, however, is not true love, and is actually quite dishonorable.

Pausanias tells us that we ought to love our lover’s soul, not their beauty or their bank account. To love either of the latter is truly a base thing, because both of these things are temporary. The beauty of youth invariable recedes, and misfortune may befall any rich man and reduce him to a peasant. Where will your love be then? It will take wings and fly!

“Evil is the vulgar lover who loves the body rather than the soul, inasmuch as he is not even stable because he loves a thing which is in itself unstable…” –Plato (Symposium)

So don’t love your spouse’s beauty and don’t love their account balance. What do you love? Their virtue!

“There remains only one way of honorable attachment which custom allows in the beloved, and this is the way of virtue.” –Plato (Symposium)

Okay, so Plato isn’t telling us that, come next Valentine’s Day, we write on the card, “Dear Honey, I love your virtue.”

Instead, he is telling us that we ought to be drawn to a person for their inner qualities. We should fall in love with the beauty of their soul and its capacity for virtue and goodness.

Pausanias tells us that we ought to love our lover’s soul, not their beauty or their bank account

Moreover, we should, ideally, find somebody who has different virtues than us. This is where the whole “let your lover change you” thing comes into play.

Find somebody who has different qualities than you. Perhaps they are brave when you are timid. Maybe they are organized while you are messy. Whatever the situation, you should find somebody who possesses qualities that you yourself lack, and then let that person seduce you into becoming a better version of yourself.

True love does not mean loving your spouse for who they are right now. True love means that two people are committed to educating each other in the ways of virtue and enduring the stormy seas that result of such a union.

“This is that love which is the love of the heavenly goddess, and is heavenly, and of great price to the individual and the cities, making the lover and the beloved alike eager in the work of their own improvement.” –Plato (Symposium)

Make sense?

So the next time you think your spouse is trying to change you, just remember that they probably are, and you really ought to let them.