The Man Who Made Stoicism Cool

What is it, then, that arouses your discontent? Human wickedness? Call to mind the doctrine that rational creatures have come into the world for the sake of one another, and that tolerance is a part of justice… (Meditations, 4.2)

If I remember, then, that I am a part of such a whole, I shall be well contented with all that comes to pass; and in so far as I am bound by a tie of kinship to other parts of the same nature as myself I shall never act against the common interest, but rather, I shall take proper account of my fellows, and direct every impulse to the common benefit and turn it away from anything that runs counter to that benefit. And when this is duly accomplished, my life must necessarily follow a happy course, just as you would observe that any citizen’s life proceeds happily on its course when he makes his way through it performing actions which benefit his fellow citizens and he welcomes whatever his city assigns to him. (Meditations, 10.6)

Donald J. Robertson, Writer and Cognitive-behavioural Psychotherapist, author of “The Philosophy of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy”

The ancient Cynic and Stoic philosophers were very interested in food. (At the end of this article you’ll even find a modern recipe for Stoic soup.)

They talk both about what we should eat and how we should eat it, if we want to live wisely and gain strength of character. For instance, we’re told of the Stoic teacher Musonius Rufus:

He often talked in a very forceful manner about food, on the grounds that food was not an insignificant topic and that what one eats has significant consequences. In particular, he thought that mastering one’s appetites for food and drink was the beginning of and basis for self-control.

Musonius taught that Stoics should prefer inexpensive foods that are easy to obtain and most nourishing and healthy for a human being to eat. It might seem like common sense to “eat healthy” but the Stoics also thought we potentially waste far too much time shopping for and preparing fancy meals when simple nutritious meals can often be easily prepared from a few readily-available ingredients.

Musonius advises eating plants and grains rather than slaughtered animals. He recommends fruits and vegetables that do not require much cooking, as well as cheese, milk, and honeycombs. The Stoic weren’t strictly vegetarian — unlike their philosophical cousins the Pythagoreans. Some Stoics were probably vegetarian and others not, although they wouldn’t have eaten very much meat in general.

Zeno of Citium, the founder of the Stoic school, had for many years been a Cynic philosopher. “Zeno”, we’re told, “thought it best to avoid gourmet food, and he was adamant about this.” He believed that once we get used to eating fancy meals we spoil our appetites and start to crave things that are expensive or difficult to obtain, losing the ability to properly enjoy simple, natural food and drink.

We know more about the Cynic diet because it was simpler and more austere. The Cynics were known, typically, for drinking water (instead of wine), and eating barley-bread and lentil soup or lupin beans — all very cheap ingredients. One Cynic letter says: “It is not only bread and water, and a bed of straw, and a rough cloak, that teach temperance…” We’re told of Crates, the Cynic teacher of Zeno, who abandoned his fortune:

Having adopted simpler ways, he was contented with a rough cloak, and barley-bread, and vegetables, without ever yearning for his former way of life or being unhappy with his present one.

The Stoics were generally more urbane and less extreme than their Cynic predecessors, and their diet seems to have been a bit less restricted. However, right down until the time of the last famous Stoic of antiquity, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, we hear about some Stoics modelling themselves on the Cynic lifestyle, which in turn appears to have been influenced by aspects of the notorious Spartan agoge or training.

For example, in a letter to Marcus Aurelius, we find his rhetoric tutor and family friend, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, joking about how he saw one of the emperor’s little sons clutching a chunk of brown bread, “quite in keeping with a philosopher’s son.” In another letter, we get a glimpse of Marcus’ eating habits:

Then we went to luncheon. What do you think I ate? A wee bit of bread, though I saw others devouring beans, onions, and herrings full of roe.

Musonius also thought we should train ourselves to avoid gluttony:

Since this behavior [gluttony] is very shameful, the opposite behavior — eating in an orderly and moderate way, and thereby demonstrating self-control — would be very good. Doing this, though, is not easy; it demands much care and training.

Stoics should eat slowly and with mindfulness of their own character and actions, paying attention (prosoche) to their thoughts and actions. They should use reason to judge where the boundary of what’s healthy lies and exercise moderation wisely.

The person who eats more than he should makes a mistake. So does the person who eats in a hurry, the person who is enthralled by gourmet food, the person who favors sweets over nutritious foods, and the person who does not share his food equally with his fellow-diners. […] Since these and other mistakes are connected with food, the person who wishes to be self-controlled must free himself of all of them and be subject to none. One way to become accustomed to this is to practice choosing food not for pleasure but for nourishment, not to please his palate but to strengthen his body.

That very simply means making an effort to eat healthy food. However, for Stoics the main reason for doing this isn’t just to improve our health, paradoxically, it’s to strengthen our character by exercising self-awareness and the virtue of self-discipline. That’s important today because we’re bombarded with contradictory advice about the healthiest way to eat. The Stoics would say that we shouldn’t allow that to confuse us. We should make a reasonable decision and stick to it in order to develop self-control because that’s fundamentally more important than losing weight or becoming physically healthy anyway. To be clear, both goals are of value, but for Stoics the primary goal is strength of character and physical health, while “preferred” as they phrase it, is of secondary importance.

Therefore, the goal of our eating should be staying alive rather than having pleasure — at least if we wish to follow the sound advice of Socrates, who said that many men live to eat, but that he ate to live. No right-thinking person will want to follow the masses and live to eat, as they do, in constant pursuit of gastronomic pleasures.

Many people who follow Stoicism today also employ intermittent fasting. It’s likely that some ancient Stoics did too, I think. Socrates famously said that “hunger is the best relish”, alluding to the irony that we actually enjoy our food more when we’re hungry, and spoil our appetites when we over-indulge. I fast at least once a week, sometimes eating and fasting on alternate days. For lunch I tend to eat dakos, a simple Cretan salad made from barley-bread rusks, perhaps like the ancient Spartans and Cynics used to eat, and a few common ingredients like chopped tomatoes, olives, and feta.

I think Musonius, and the other Stoics, would also approve of the recipe below because it’s very cheap, mainly uses common vegetable ingredients, which are easy to obtain, and it’s also very easy to prepare. You can easily make a large batch and store it in portions to reheat later. It’s unfussy but tasty and nutritious.

In Meals and Recipes from Ancient Greece, Eugenia Ricotti describes the following recipe called “Zeno’s Lentil Soup”. It’s a modern recipe loosely based upon ancient sources, including remarks attributed to Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoic philosophy, which are found in the Deipnosophistae (or “Dinner Experts”) of Athenaeus of Naucratis.

1 lb. (450g) lentils

8 cups (2 litres) broth

1 large minced leek

1 carrot, 1 stalk of celery, and 1 small onion, all sliced

2 tablespoons vinegar

1 teaspoon honey

olive oil

12 coriander seeds

salt and pepper to taste

She says to rinse the lentils and put them in a pot with the broth to boil. Then reduce heat and simmer for one hour. Then skim the top, add the vegetables, and leave to simmer until cooked, which should be about 30 minutes. She says that if it seems too watery either add cornstarch or pass some of the lentils through a sieve. Finally, add vinegar and honey for flavour.

After pouring into serving bowls, add a good amount of olive oil — she suggests about 2 tablespoons per serving. Finish by sprinkling on the coriander seeds and adding more salt and pepper to taste.

I’ve made this recipe quite a few times myself. I use dried green lentils, which I soak overnight and boil for a few minutes. I use red wine vinegar and often add a couple of garlic cloves and perhaps a few bay leaves, possibly also a little paprika. I’d also usually garnish it with a few fresh coriander leaves and serve with bread. This is a photo of my version…

[First seen on Medium.com]

Marcus Aurelius is a pop icon. Well, almost…

Don’t get me wrong – I’m definitely a fan of this up and coming trend. I like to think of him as a gateway drug to philosophy and the classics.

I’m also not one of ‘those’ classics lovers who only like obscure references and lesser known historical figures. Just because Marcus Aurelius is popular, doesn’t mean he doesn’t have something to contribute. In fact, I think he is enjoying success for the very reason that he is so relevant, despite being basically a king who died over 1800 years ago.

I know some ask, how can a Roman emperor be helpful to us in the here and now? What does his life have to do with ours?

Well, more than you might first imagine.

It’s actually something that cognitive psychotherapist and one of our keynote speakers at Classical Wisdom’s Inaugural Symposium, Donald Robertson, explains eloquently in his widely successful book, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor.

As many of you know, Marcus Aurelius was the final famous Stoic philosopher of the ancient world and The Meditations, his personal journal, survives to this day as one of the most loved self-help and spiritual classics of all time.

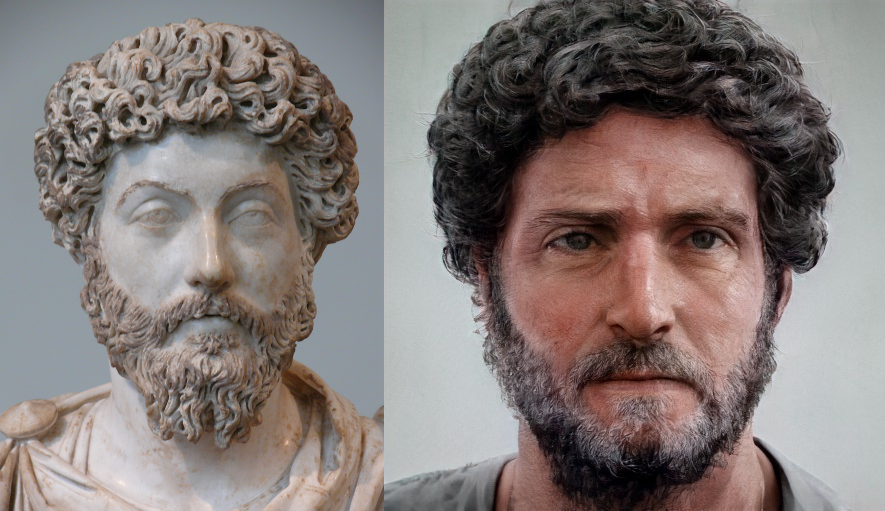

Modern super realistic depiction of Marcus Aurelius from https://cesaresderoma.com/

In How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, Donald Robertson weaves the life and philosophy of Marcus Aurelius together seamlessly to provide a compelling modern-day guide to the Stoic wisdom followed by countless individuals throughout the centuries as a path to achieving greater fulfillment and emotional resilience.

How to Think Like a Roman Emperor takes readers on a transformative journey along with Marcus, following his progress from a young noble at the court of Hadrian―taken under the wing of some of the finest philosophers of his day―through to his reign as emperor of Rome at the height of its power.

An impressive feat, of course… but what does his life have to do with us, you may ask?

Robertson does an excellent job in showing just how Marcus used philosophical doctrines and therapeutic practices to build emotional resilience and endure tremendous adversity…. He goes even further to guide readers by applying the same methods to their own lives.

Combining remarkable stories from Marcus’s life with insights from modern psychology and the enduring wisdom of his philosophy, How to Think Like a Roman Emperor puts a human face on Stoicism and offers a timeless and essential guide to handling the ethical and psychological challenges we face today.

And let’s be honest… we could all use a bit more emotional resilience these days!

You can purchase Donald’s excellent and insightful book here.

You can also watch Donald speak LIVE at the Classical Wisdom’s Online Symposium, taking place October 24-25.

Donald Robertson will be speaking LIVE at our Classical Wisdom Symposium both in his own presentation on Politics and Anger in Marcus Aurelius and on the panel discussion: What power does the individual have in Politics?

Make sure to check out all the details of our Symposium below!

Written by Lydia Serrant, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

‘’You have power over your mind – not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength’’ ~ Marcus Aurelius

Are you finding yourself struggling with both expected and unexpected changes in your life? Change is common to the human experience, and no one understood this better than the ancient stoics.

Stoicism was a philosophy that spread throughout ancient Greece and Rome from the 3rd Century BC and was popular among all classes of society for around 400 years. The three most prominent stoics of the time were Seneca the Younger, a playwright and empirical advisor; Epictetus, who rose from slave to teacher; and last but certainly not least, Marcus Aurelius ‘The Philosopher Emperor’ who ruled Rome between 161-180CE.

The stoics were no strangers to unwelcome change. Stoics had their fair share of opponents and more than once found themselves on the wrong side of the law. Emperor Nero particularly opposed the Stoic thinkers, despite the fact that he was once a student of Seneca. Those that Nero did not sentence to death were banished from Rome, where they further developed Stoic philosophy in exile.

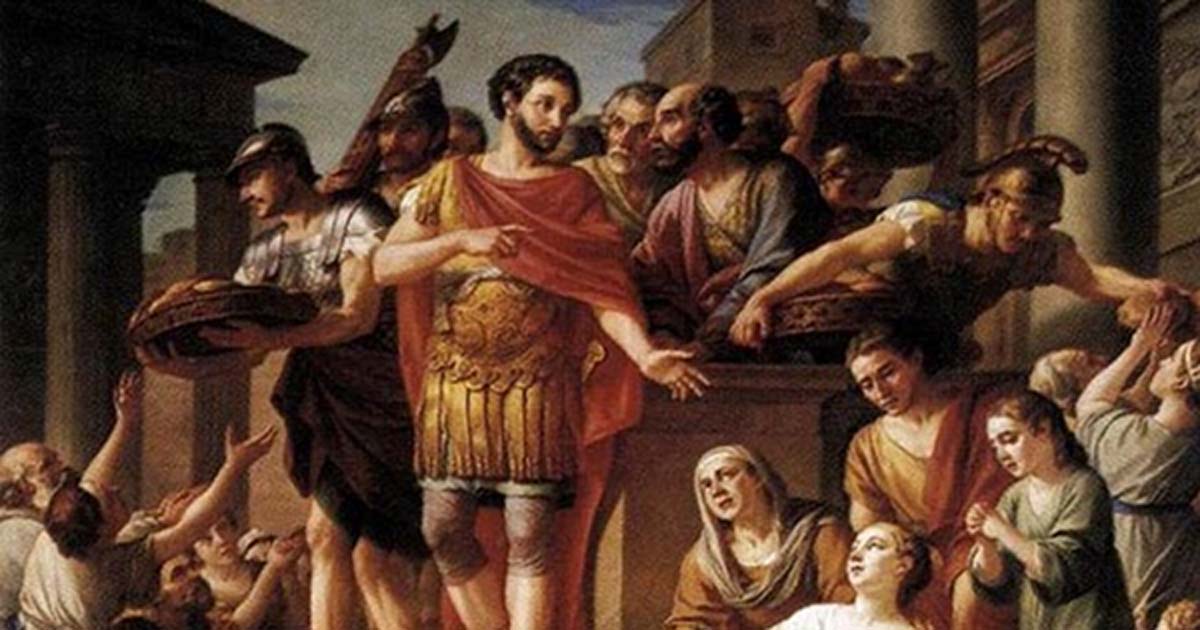

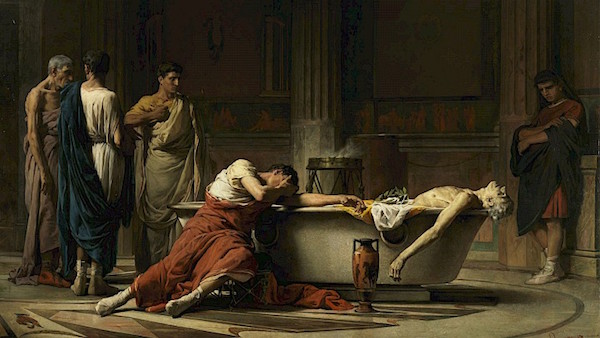

The Death of Seneca, by Manuel Domínguez Sánchez.

During his exile in Corsica, Seneca wrote that his change in circumstance was not at all that bad. Seneca believed that change is nothing but a change of place, mentally or physically. And you will often find people in the same place of their own free will.

According to Stoic Philosophy, it is a state of mind, rather than circumstance, that creates the true challenges and adversities associated with change.

Common resistance to change

The problem with change is that most of the time, we like things the way they are. Even if your life is not a comfortable one, most people prefer to stick with the ‘Devil They Know’ than to venture out into the great unknown.

It is tempting to cling to daily rituals. Having systems and routines in place provides a sense of security. We are not taught to see the growth that can be had in change, instead, we are told to try to get things ‘back to normal’ as closely and as quickly as possible.

The Death of Seneca, Simon Francios Ravenet I , 1768.

The Stoics knew that without change, none of us would exist. The universe itself had to undergo several stages of change before Life itself could be allowed to exist. Marcus Aurelius wrote that ‘Change is natures delight’ meaning that change is actually woven into the universe. We humans are built for change and embracing new challenges is an opportunity for growth and development.

“Frightened of change? But what can exist without it? What’s closer to nature’s heart? Can you take a hot bath and leave the firewood as it was? Eat food without transforming it? Can any vital process take place without something being changed?

Can’t you see? It’s just the same with you—and just as vital to nature.” ~ Meditations, Book VII.18

Most of the fear around change is that we often fear that change is bad. Seneca once wrote, ”We are more often frightened than hurt, and we suffer more in imagination than in reality.”

Most often it is our thoughts, rather than the change itself, that is the source of our resistance to change.

Bust of Marcus Aurelius

As humans, we have a tendency to run scenarios through our heads before the event itself actually happens. This is great for preplanning and strategy, however, we run into problems when our minds automatically run through the ‘worst-case’ scenarios that may or may not actually happen.

Most fears around change come from our in-built aversion to suffering and our tendency to over-plan for suffering avoidance. Suffering and change are often linked – or at least we perceive that they are always linked. But don’t worry, the stoics have a remedy for that too!

Change and Suffering

The relationship between change and suffering is often described in two phases. Firstly, that we suffer in our anticipation of change and the shift away from our routine or the anticipation of loss (e.g., a loved one, a job, a home).

The second phase is the reaction to a change that has already happened. It is about coming to terms with a loss (person or circumstance) and the anticipation of finding balance or carving a new path for ourselves out of the chaos.

Rome, Italy. Piazza del Campidoglio, with copy of equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius. The original is displayed in the Capitoline Museum.

The stoics overcome this by reminding themselves about how relatively small and unimportant we are as individuals. Sounds harsh and counterintuitive right? Yes. But when you consider the grand tapestry that is life and universe, our part is rather small.

“Consider the lives led once by others, long ago, the lives to be led by others after you, the lives led even now, in foreign lands. How many people don’t even know your name. How many will soon have forgotten it. How many offer you praise now—and tomorrow, perhaps, contempt.” ~ Meditations, Book IX.30

This is what today’s society refers to as the ‘Ego check’. In other words, who are we to expect to go through life without any changes or challenges?

Epictetus advises that we play fate at its own game. Instead of resisting and battling change (which is a waste of time if the change has already occurred), we should learn to embrace change and make an opportunity out of adversity.

This is easier said than done of course, but you’ll find that working this mindset into your daily life will make the process of change run a whole lot smoother.

Artistic impression of Epictetus, including his crutch.

Improving your relationship with change

“It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters’’ ~ Epictetus

The bottom line, according to the stoics, is that the best way to deal with change is to try to change your mindset. Happiness depends more on values than the current state in which you reside.

Of course, basic needs must be met such as food and shelter, but the Stoics argue that change itself is not able to deprive you of the ability to endure.

Change has changed people for the better. It was exile from Sinope that lead Diogenes of Sinope to Athens where he went on to become one of the founders of the Cynic School of Philosophy. Had he remained in Sinope he likely would have continued his life as a banker and his name would have disappeared into obscurity.

No matter the circumstance brought about by change, your place in nature and your virtues still remain. Even in the most challenging of times, true friends will not refuse to associate with you and change does not stop you from associating with new people. In other words, the change may come as a pleasant surprise, if you keep an eye out for silver linings.