By Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Having been inhabited for roughly 5,000 years, Thebes possesses a wealth of history and culture. Thebes is located in central Greece and garnered military might and political power, not least of which resulted from their leadership in the Boeotian League and the Sacred Band of soldiers in the 4th century.

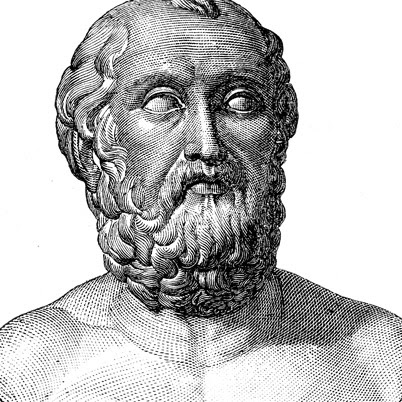

Plan of Thebes

Archaeological excavations have revealed fortified buildings with rock-cut foundations as well as courtyards (stone-paved) and mud brick walls dating back to the 3rd millennium BC. Around 2500 BC, we see evidence for food and wool production and trade, thanks to recovered grinding stones and terracotta loom weights and spools.

Jumping ahead to the Mycenaean period, Thebes boasted a Mycenaean palace called Kadmeion, located in the center of the acropolis. It was a large independent structure comprised of corridors, rooms for work and storage, as well as workshops that were vital to the existence of Thebes. Also found were Linear B tablets and seal stones, along with Cretan stirrup jars, that demonstrate that Thebes had widespread contacts in the Aegean. While the trade alone is not surprising for this time period, it does help us understand the role and significance Thebes played early on.

The Mycenaean Palace, or Kadmeion, dates from the 13th century BC and is located almost centrally on the acropolis.

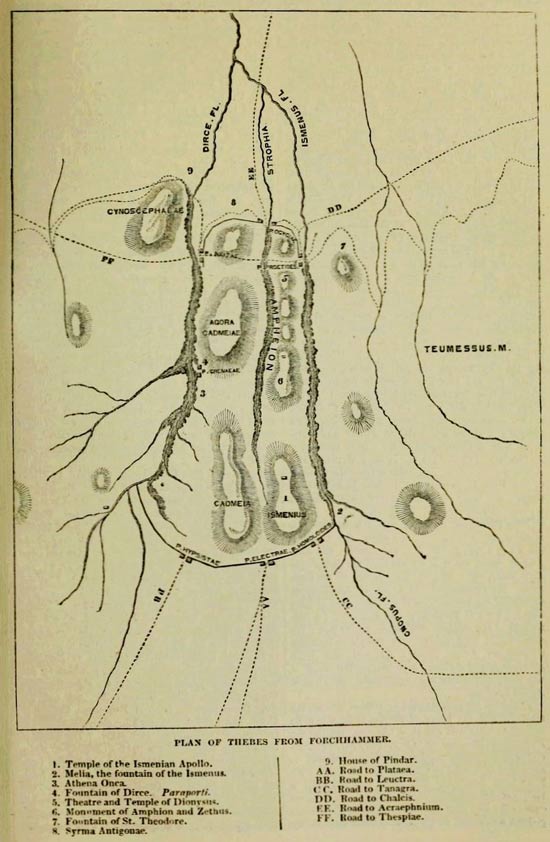

Around 1200 BC the Mediterranean was swallowed up in a relatively indecipherable fog… however, Thebes emerged again in the Archaic period with infrastructure and power. Soon, they forged an antagonistic relationship against Athens and Sparta, fighting almost constantly for regional dominance. It didn’t help Thebes’ image throughout Greece either that they sided with Persia and Xerxes in 480 BC during the Persian War.

After the Persian War, there was relative quiet, save for the rising tensions among the Greek powers themselves. Thebes needed to be punished for their alliance with the Persians, and so was stripped of the head seat at the Boeotian league.

Historical Atlas of the Mediterranean/Persian Wars

However, not soon after, Sparta needed support against Athens in central Greece and enlisted Thebes to take up the position. By 431 BC, there was an all out war (the Archidamian War) between allies Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes against Athens which lasted until 421 BC. After the Archidamian War, there was the Decelean War (415 BC -404 BC) and the Corinthian War (395 BC – 387 BC, Thebes Corinth, Argos, and Athens against Sparta).

Turmoil abounded (with Thebes often highly involved) until the invasion of Philip of Macedonia. In 338 BC, Thebes joined Athens and Corinth, setting aside a rivalry going back hundreds of years in order to stand against the Macedonians. We all know the result; eventually Thebes was destroyed by Alexander the Great and the population was sold into slavery.

The subsequent years saw Roman visits and rebuilding, population depletion, and finally becoming a provincial town in the Roman Empire. The zenith of Thebes had come to an end long before, though its mythology still lives on.

Mythology in Thebes

The Seven Against Thebes

Like most Greek cities, Thebes has a foundation myth that connects its people to the gods. In the case of Thebes, it was founded by Kadmos (or Cadmus), son of Egenor and brother of Europa. While specifics change depending on who is reporting the story, the basics remain that Kadmos was to sow the teeth of a giant serpent (that he had previously slain) into the ground. From this spot a group of warriors sprang from the earth, and they fought and battled to found the city of Kadmea.

Another prominent myth, that again has to do with a psuedo-foundation, is Seven Against Thebes. In this story, Oedipus’ two sons, Polyneikes and Eteokles, embroiled themselves in a war. After Eteokles exiled Polyneikes, he enlisted the help of the Achaeans to take back the city of Thebes. Seven warriors, including Polyneikes, started their assault on the city and began scaling the walls. Even though six out of the seven were killed, the attack was successful and Polyneikes (though dead) took back the city from his brother.

Famous People from Thebes

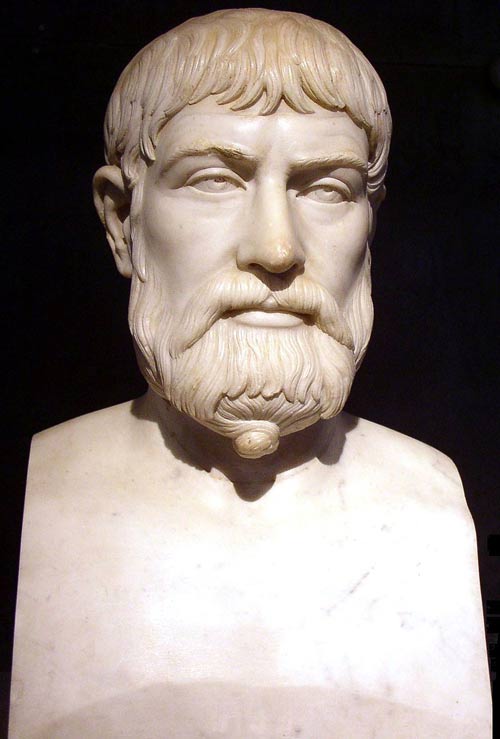

Pindar, Roman copy of Greek 5th century BC bust (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples)

Perhaps three of the most notorious people from Thebes are Epaminondas, Pelopidas, and Pindar.

Epaminondas (born around 418 BC and died 362 BC) was a military general and student of philosophy. He commanded the Theban forces at pivotal battles such as Leuctra, where the Thebans delivered such a decisive blow to the Spartans that a monument was erected, as well as the Battle of Mantinea where he died in battle.

At the same time as Epaminondas, Pelopidas campaigned in Central and Northern Greece, and died in the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 364 BC. He was successful in the battle though and overthrew the Thessalian troops of Alexander of Pherae.

However, the most recognizable celebrity to come from Thebes may certainly be Pindar, the poet of paeans, songs, and hymns. Though fragmentary, we do have 45 of his lyric odes, or epinicia, to honor notable people. Pindar authored a style that was mirrored by Latin poets, like Horace, and was popular material for Byzantine literature. In 1896, a “Pindaric Ode” was created for the Olympic Games in Athens, similarly copied as recently as 2012.

Contributions from Thebes

Among the literature, mythology, and fodder for excavation that Thebes has provided us, she also left behind a legacy of political contributions. In 378 BC, Thebes remodeled their constitution and established a democracy and the Boeotian federation. This new and somewhat radical type of “democratic Federalism” provided direct federal citizenship to those in her domain.

Another contribution Thebes provided is the so-called Theban “hegemony.” This was the period after the Theban victory at the battle of Leuctra, where for decades Thebes held powerful influence and loyalty in Greece, acquired not by military occupations but by lucrative alliances maintained throughout the region.

An, although mythic, Kadmus is credited with bringing the alphabet to Thebes from the east, a contribution that would have inhibited Theban growth in subsequent years.

By Julia Huse

When it comes to Ancient Greece I am particularly

Spartan Warrior

Spartan Warriorfond of Athens. As the birthplace of democracy, the epicenter of Greek tragedy, and the intellectual hub of the classical age, Athens had a lot going for it.

Today, however, we look elsewhere. Classical Athens, after all, wasn’t the only place where new and dramatic changes were taking place.

You might be familiar with Sparta, the intensely militaristic city-state of the Ancient world made famous by the movie 300.

Imagine if the United States Marine Corp founded and governed their own country.

That would be Sparta…

Key players in the Greco-Persian War, we often admire Sparta for its toughness and courage. With a focus on its military, however, we hardly ever hear about its government. This is a real shame because Sparta had its own unique political system with two, count them, two kings sitting on the throne at once.

In his Histories, Herodotus explains to us how this dual kingship came about. A Spartan king named Aristodemus had twin sons. Almost immediately after the two boys were born Aristodemus croaked. The Spartans were then faced with a dilemma; who was going to be Aristodemus’ successor? The Spartans wanted to make the older of the twins the new king, as was custom, but the two boys were so “alike and equal” that they could not determine which of the two was the older twin. The Spartans then turned to the mother of the twins, Argeia, who told the Spartans that she couldn’t even tell them apart. This was a lie. She knew which of the two was older but she wanted both her sons to become king.

So the Spartans, not sure what to do, did what any good city-state would do at the time: ask the oracle at Delphi.

When they asked the Pythia (for those who don’t know the Pythia was the priestess at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi who gave the oracle), she told the Spartans to make both the boys king. From that point on the Spartans had two kings, one from the lineage of each twin. As the twins grew up they were in constant competition with each other, which then became an important part of the dual kingship.

These kings were equal in every sense. Both kings dealt equally in the matters of religion, laws and military. Over the years, however, the say that the two kings had in these matters dwindled. By the 5th century BC most of their judicial duties had been handed over to the ephors, a democratically elected group of law makers, and the gerousia, a group of 28 elders elected for life normally part of royal households. Even though their judicial power had been reduced, the kings still held a decent amount of military power.

Either king could lead armies in to war with the approval of certain councils, but it was not permitted for both the kings to lead an army at the same time. One king always had to remain in Sparta in order to prevent anarchy, or the ever-frequent helot (slave) uprising.

The idea of monarchy in Sparta was clearly very complicated. Not only does the “mono” part of monarchy not really apply to their dual kingship, but also the power of these kings were closely regulated and controlled by other councils in their government. This rather odd form of monarchy was somewhat genius in its own way though. Not only did these kings have two councils to check their power, the competition between the two kings kept them in line as well.

The kings held opposing opinions on issues, thus providing a voice for citizens on either side of the issue. Also, making one king always remain in the city ensured order and calm for the Spartans even in times of war. The nature of the two councils also had added benefits. The relative permanence of the gerousia provided stability in their government while the annually elected ephors allowed the Spartans to have a voice in their government.

This whole system seems very similar to the perfect government described by Cicero in his De Re Publica with its mixture of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. Have we been so distracted by democratic Athens that we’ve missed the odd genius of the Spartan political system?

Now, I’m not calling for a modern revival. I’m not saying that the United States, just as an example, should elect two presidents. Put Hillary AND The Donald in office; let them sort it out amongst themselves.

Yeah…that would work.

But for the ancient Spartans, it DID work, for a while at least.

The next time you think of Sparta, put out of your mind the image of behemoth warriors in leather speedos. Instead, perhaps remember the ancient Spartans as innovative, dare we even say revolutionary, political thinkers.

By Ben Potter

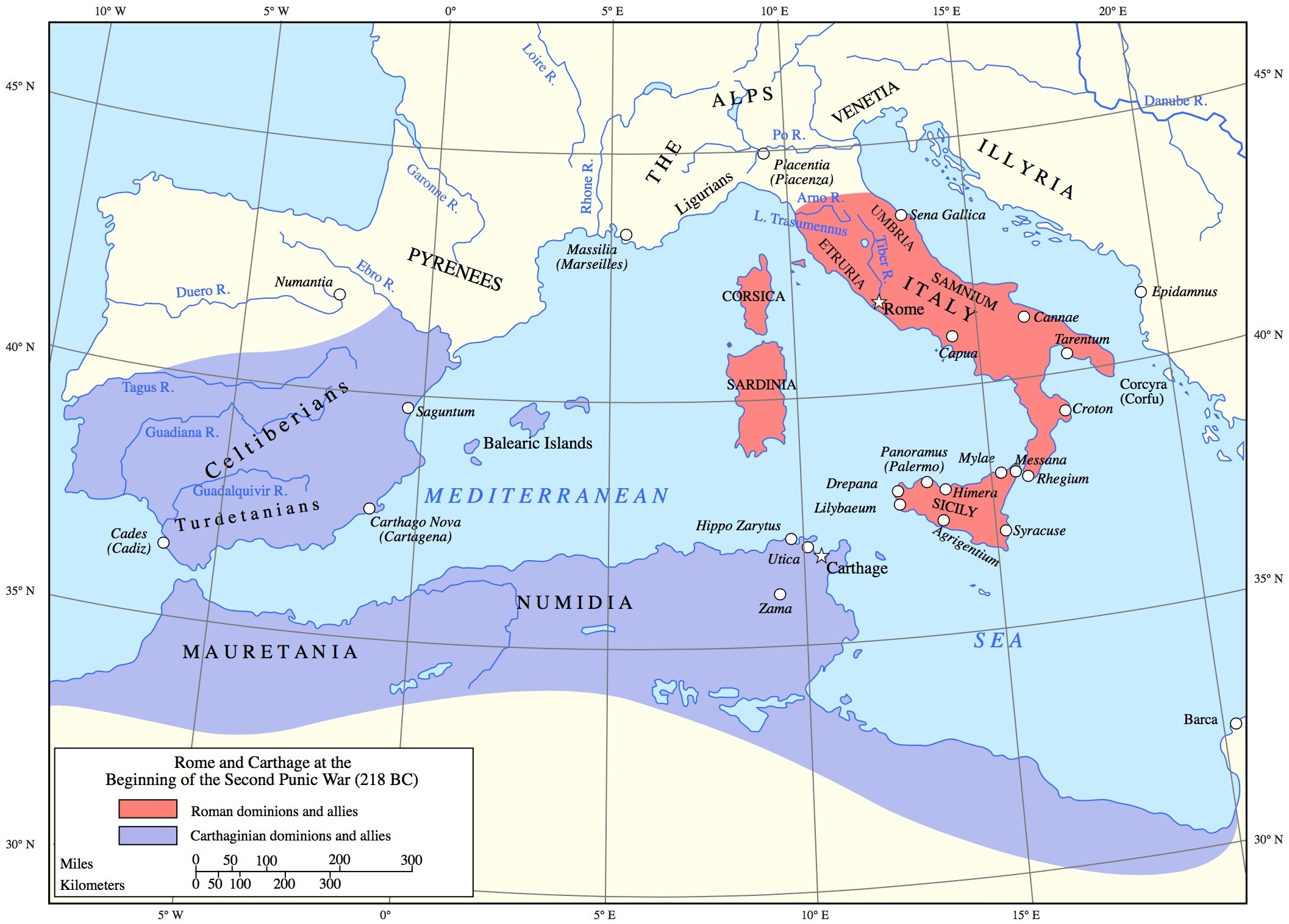

What do Spain, Portugal, Malta, Gibraltar, Libya, Morocco, Italy and France have in common?

Weather… perhaps. Food… some. Sea? Ah! Now we’re warming up!

What if we throw into the mix the names Bomilcar, Hasdrabul, Hamilcar and Terrence?

If you’ve got the answer, well done!

If you haven’t, then it’s probably because I’ve been tricky, having omitted the key place, person and animal associated with this land; they are Tunisia, Hannibal and the elephant, respectively.

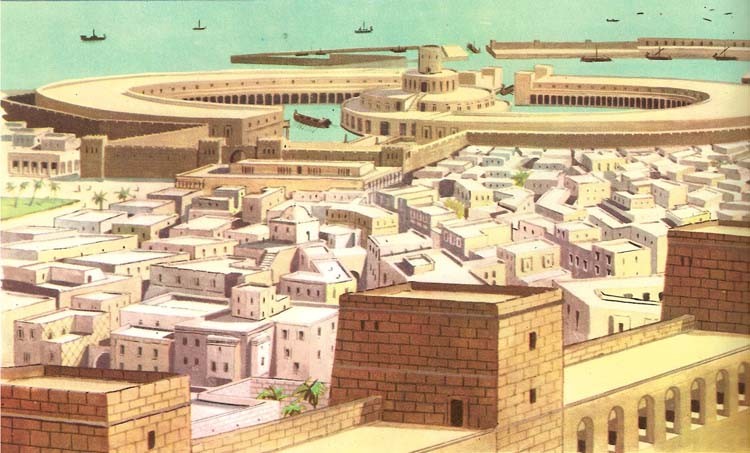

Yes, ladies and gentlemen, today we will be looking at that erstwhile champion of the Mediterranean, the forgotten superpower of the ancient world, Carthage!

The inhabitants of this land, originally a large peninsula which washed into the gulf of Tunis, often have to play second, or indeed third fiddle, in the annals of history to their Greek and Roman neighbours.

It is perhaps a quirk of geography that casts Carthage in shadow. While the Hellenes and the Latins understandably dominate proceedings, ancient-lovers’ who are drawn towards Africa are normally met with pyramids, sphinxes, and the hypnotic eye of Ra.

This rings more true when combined with the fact that this impressive society never quite managed to become truly imperious… though they often came close.

One could say that geographically and historically Carthage has been always the bridesmaid…but never the bride.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves; let us begin at the beginning.

Legend has it that Carthage was founded out of the Phoenician stronghold of Tyre (in Lebanon) in the latter part of the ninth century BC.

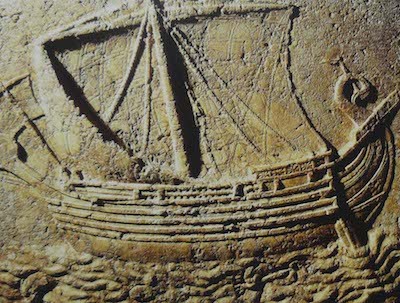

Archaeological verification is yet to be made within a century of the date, but the influence of those great Semitic traders and seamen, the Phoenicians, is certain.

Less so is the idea that Carthage’s first ruler was the mythical and tragic queen Dido.

Whatever her origins, Carthage became an essential port, first rivalling, and then outstripping, its motherland. This was due to its fine farmland, two excellent harbours, important strategic position and judicious buying and selling of commodities from as far afield as Britain and the Canary Islands.

Its trade of precious Iberian metals, and especially its monopoly of tin ore, meant that…ahem…unalloyed wealth streamed into the colony. Indeed, without this booming industry the Bronze Age might have existed in only a nominal sense.

Though practical metals were far from the be-all-and-end-all of Carthaginian trade.

Their immense fleets (both trade and naval) saw them wheel and deal in lead, stones, garum (a salty fish sauce used as a condiment), fish, skins, hides, ivory, salt, exotic animals, timber, textiles, glass, pottery, wine, gold and the pound-for-pound most valuable commodity of the ancient world, purple dye.

Thus Carthage was not merely the marketplace of the Mediterranean, it was the very conduit from which other cities were able to become cosmopolitan.

Though loyalists might baulk at the suggestion that, without trade, Carthage would have been nothing, we can confidently state that no other ancient civilization (and perhaps no modern – discuss!) was so dependent on foreign commerce as was this one.

But just how, as they were initially in the thrall of Tyre, did Carthage manage to manoeuvre itself into a position to be a major Mediterranean player?

Well, first it gained its independence from the Phoenicians around 650 BC.

Though the fledgling state seems to initially have been governed along monarchical lines, there is evidence for an advanced and sophisticated political system via the adoption of an oligarchic constitution by the sixth century BC.

However, the break from their Phoenician forefathers (who were being overrun by the Persians) was not merely a functional or symbolic one; this was not a simple taxation vs. representation equation.

What occurred would have been the equivalent of the 1776 United States of America becoming lord and master of parts of India, Canada, South America and Africa!

Yes, with an unfettered vim, Carthage went about exerting hegemony over the key Tyrian trading posts and colonies of the Mediterranean basin. The effect of which was not merely the establishment of a trading realm, but of a full-blown (and capital-lettered) Empire!

Indeed, by 509 BC Carthage’s rampages forced Rome to sign a treaty recognising that these seafaring swashbucklers had control over both Sardinia and Sicily.

With regards to the inland areas of Africa, the Carthaginians (generally) made peaceful treaties with the indigenous peoples therein. It is quite likely such pacts were eagerly signed as Carthage had enough coin to hire half the mercenaries of Europe and decimate the African hinterland… should she have wished to do so.

But it was the fascination with Sicily that set Carthage on an inevitable crash course with the Greeks, themselves keen to expand their sphere of influence into what became known as Magna Graecia.

This now quintessentially Italian isle was anything but in the ancient world and for 200 years (from the fifth century BC onwards) it set the stage for a tit-for-tat war between the Greeks and Carthaginians.

Carthage was peerless in naval terms, but its small native population necessitated an overreliance on mercenaries. For whatever reason, these swords-for-hire never quite managed to overwhelm or intimidate the Greeks into submission.

Susceptibility to plague and a formidable opposition meant that Carthage, though never losing its foothold in the West of the island, by equal measures, never managed to drive the Greeks into the sea.

This centuries-long stalemate not only cost both sides time, men and money, but it had another effect. It allowed the Roman Republic to slowly blossom into a major player while their two most likely rivals slugged it out down south.

Indeed, Greek mistakes were often at the heart of Roman expansion.

The most famous example is Pyrrhus, king of Epirus and Macedon (remembered today though the expression ‘a pyrrhic victory’), who looked to expand his empire.

He assaulted Rome and Sicilian Carthage, which briefly made the two states allies to counter his machinations (to the Carthaginians eventual downfall). His failure gave Rome the casus bellum to assimilate the Greek portion of the Italian peninsula.

This meant that when Carthaginian ships were stationed in the stretto di Messina (between Italy and Sicily), Rome’s newly swollen boundaries were suddenly under threat.

What happened next is well known: The Punic Wars, Hannibal and his elephants, initial success, and ultimate failure.

The battle of Zama (202 BC) between Hannibal and Scipio Africanus was a catastrophic defeat for the Carthaginians. Rome was on the path to greatness, while Carthage, a forlorn and broken foe, was left to muse over that saddest of sad reflections: ‘it might have been’.

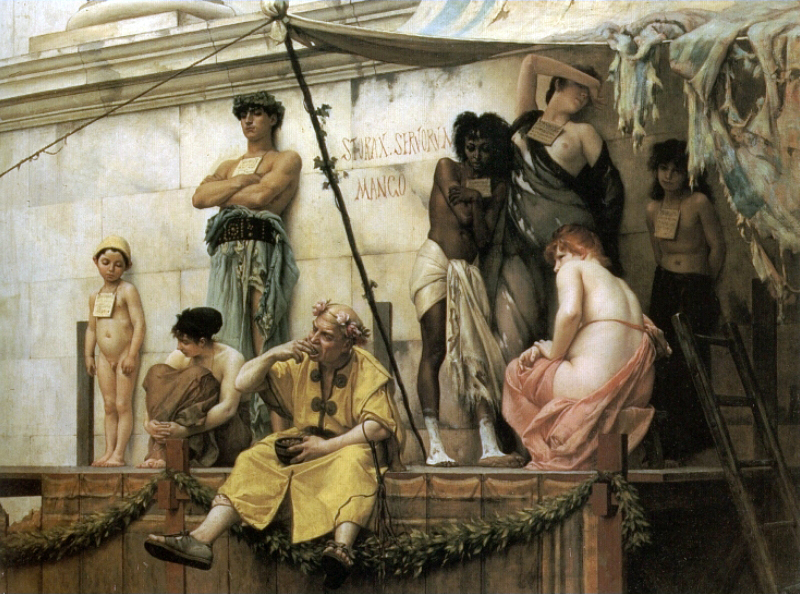

146 BC saw the annihilation of Carthage, its earth salted, and its population enslaved or massacred. Crucially for the fate of world history, this meant that Rome was now the dominant force in the region, with a greatly expanded empire and without any serious military rivals.

Though it is never expedient to play ‘what if…’ in such situations, it is a simultaneously sobering and humbling thought to think that Western civilization may have hinged on the outcome of this moment.

Rarely does history roll over the points in such a clear and stark fashion, but this is one moment we can pinpoint and say from here on in… Europe had Africa in its thrall.

Though that’s not to say this was quite the end of Carthage; it’s difficult to keep a good people down after all. Like the proverbial phoenix, Carthage rose again, albeit under the auspices of Rome.

The age of emperors saw a renaissance in the colony with Augustus (understandably shy of tempting fate in Egypt) making it the base for his proconsul to Africa.

As Africa was swelling the Empire’s breadbasket, providing it with a vital corn supply, Carthage became more and more important. Within 200 years, it was second only to Rome itself in the western Mediterranean.

In addition, the great city became a bastion of both education, producing or polishing great orators and lawyers, and of Christianity. The bishop of Carthage was Rome’s number two (at least according to the man himself).

Overlooked, undervalued, and a postscript to the main attraction… even so, Carthage somehow survived the sword and salt of Rome.

True, it may have had little in the way of original and distinctive art as well as a pagan pantheon that was derided by contemporaries (for its practice of child sacrifice). Nonetheless, it is well worth more than a mere fleeting thought.

Through us, Carthage lives on… and will continue to do so as long as men and women through the ages occasionally rise a glass and a smile to the bridesmaid who never quite got the breaks to become a bride, but without whom the wedding would hardly have been worth attending.

By Ben Potter

Athens, July 514 BC. Two of Athens’ most disgruntled sons, Harmodius and Aristogeiton become forever known as ‘The Tyrannicides’. With their swords plunged into the Tyrant Hipparchus, these two soon-to-be martyrs become the symbol of Athenian democracy.

This is because these brave men’s actions paved the way for Athens to unfetter herself from oppression and tyranny. Her screaming infancy was at an end; it was finally time for the demos (people) to unleash their kratos (power).

So harmony and joy ensued in what was now the cradle of democracy?

No.

Not at all.

Not even slightly.

Two issues rise starkly out of the noble intentions of our forefathers; the system… and the results.

But let’s deal with the latter first; to see if any means can justify such ends!

Athenian democracy, despite a couple of interruptions and renaissances, is generally agreed to have reigned supreme from 508-322 BC.

Those who know their important dates will see an instant red flag; didn’t KING Alexander the Great die in 323 BC? How could Athens remain an independent, democratic state while under the yoke of Macedonian imperialism? A very intelligent question; you should congratulate yourself for asking it.

Whilst Athens remained a functioning democracy during the reign of Alexander the Great, it could not in all earnest be called independent. In other words, it was a democratic client kingdom that could have easily had its powers removed should they have been used ‘irresponsibly’ (c.f. American involvement in Guatemala, Iran, Chile, Brazil, Argentina and even Greece itself).

Despite this technical independence, Athenian democracy did little to cover itself in glory… even when its self-determinism was tangible rather than merely theoretical.

For instance, the bloodthirsty rule of the people forced Athens to hubristically overstep her reach during the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), which resulted in the temporary suspension of the democratic experiment. Importantly, it also seemed suspicious of, and hostile towards, some of the greatest minds of that time.

Indeed, such was the poor judgement of the demos that it drove the city’s greatest commander (and lover), the legendary Alcibiades, to flee during the Peloponnesian War and take up residence with their antagonists, the Spartans.

It has been often speculated, and with much justification, that Alcibiades’ defection was the tipping point in the war.

However, national security was only one sphere in which the people strove to raise their own standing simply by reducing the mean quality of the demos as a whole. Art and philosophy were the chief victims of a short-sighted and covetous populace.

It’s thought that popular pressure and threat of persecution forced the tragedian Euripides to quit the city for a ‘retirement’ in Macedonia. Though some now dispute the veracity of such a story, the mere fact that it was popularly believed tells a tale in itself.

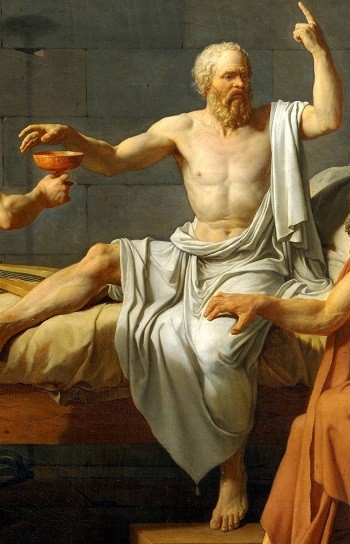

Aristotle, likewise, opted to jump before he was pushed into the next world. He was particularly concerned that the demos would condemn him to the same fate it bestowed upon Socrates.

Unlike the other three men mentioned above, Socrates was not merely chased out of town, but actually executed by a jury of 501 of his peers (greatly multiplying Herbert Spencer’s maxim that “A jury is composed of twelve men of average ignorance”).

It is this state-sanctioned murder of one of the first great minds of our culture that forever leaves Athenian democracy with an indelible stain.

But can the means do much to exonerate such rancorous ends? Well… you be the judge.

The Nuts and Bolts

Athenian democracy evolved as any ‘work in progress’ democracy should and as such the citizens contributing to the various bodies of state had sometimes more and sometimes less involvement/power at different times.

However, the really poignant thing about political participation is that it was a) assumed and b) direct.

It was taken for granted that men must not merely take an interest in or talk about politics, but perform actively within the political arena. Indeed, men who deliberately spurned politics were known as idiōtēs. While the world literally meant ‘one who minded his own business’, it was a term of the utmost disdain.

The idea that democracy was ‘direct’ meant that the votes in the Assembly (ekklêsia) were de facto referenda. Though minor votes seemed to be able to get through without much difficulty, major votes could only be passed if 6000 men were in attendance. Motions carried with a simple majority.

All free men over 18 could vote, but due to the two years of compulsory military service, political activity usually started at the age of 20. Women had to wait a bit longer… until 1952 in fact. However, this imbalance was slightly redressed by the fact that men had to be 30 in order to hold political office, sit on a jury or even table a motion!

The Boule

Despite its selectively egalitarian nature, the referendum-style Assembly was by no means a political free-for-all. The business of the day was dictated by the Council (boule). This 500 strong body was the nearest thing that Athens had to an executive or cabinet.

Even if there was no guarantee that the Council would be selected judiciously, it was at least selected randomly. 50 members of each of the 10 Athenian tribes (demes) were appointed by lot to serve for a year with members from alternating tribes taking turns to lead the Council day-by-day.

The boule also had to maintain the fleet, liaise with the generals, entertain dignitaries, assess the competence of magistrates and handle the city purse. These last two responsibilities did, for a time at least, fall in part under the remit of other organs of state.

The Courts

One of which was the courts. 6,000 judges were appointed a year and they would congregate in the agora to be assigned trials for the day.

Private cases were overseen by either 201 or 401 judges and public cases by 501. Trials were supposed to be concluded by sunset, making jury tampering and corruption not only extremely costly, but logistically impossible.

The most serious public cases seem to have been political in nature and were brought against those charged with treason, corruption, or those who proposed unconstitutional legislation in the Assembly.

N.B. it didn’t matter if the legislation had passed the vote, the individual could still be tried, condemned and even executed for misleading the demos. The demos was always immune from any form of accountability, if it acted incorrectly it was always because it had been ‘misled’.

The Archai

The day-to-day running of the mundane affairs of state was in the hands of the 1,200 archai. 1,100 of these former-day civil servants were chosen by lot with a further 100 being voted for by the Assembly. Only those voted in could hold the same office twice (with the exception, by numerical necessity, of those who went into the boule).

The Strategoi

The only offices not attainable by lot were the 10 associated with the armed forces. Consequently, these generals (strategoi) were the only people who could hope to carve out a political niche for themselves.

However, such an appointment was fraught with peril, as the demos was notoriously unforgiving of failure. The case in point being the 406 BC defeat at the battle of Arginusae. Six of the eight generals involved in this débâcle were tried en masse and executed, despite such a process being illegal.

The leader in charge of proceedings for the day of the vote was, amazingly (as it was random which citizen it could have been), Socrates. Despite refusing to allow an illegal vote to take place, the demos went ahead and committed collective treason against itself.

Some speculate that the enemies Socrates made on that day may have come back to haunt in him in 399 BC.

The Demokratia

The democrats of Athens believed that demokratia was intrinsically bound to liberty and equality; they defined the terms thus:

Liberty = the ability to live as one pleased and the freedom to participate in politics.

Equality = the right to speak in the Assembly and the right to a fair trial.

There was not even a suggestion of attempting to provide men with an equal social or financial status; democratic Athens was actually extremely snobbish and elitist.

Free-speech (parrhesia) was thought to underpin both of these. Though many critics have pointed out exercising this was precisely what cost Socrates his life.

Critics have also claimed that, in order to financially sustain such a democracy, it was necessary for Athens to extend (and then overextend) her imperial reach. This included having a slave class whose ranks were swollen far beyond those of any of her close neighbours.

Additionally, as the demos could act with impunity, when mistakes were made – scapegoats needed to be found (e.g. the 6 generals or Socrates).

That said, this was a political system without entrenched parties. Indeed, it was with few factions of any sort, with minimal corruption and, most importantly, without any concept of lobbyists!

And we cannot deny that the democratic period gave us some of the most amazing tragedians, comedians, philosophers, architects, visionaries, historians and characters the ancient world ever produced.

Would we have had the Parthenon if not for Pericles and his building plan? Or Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes if theatrical festivals, competitions and prizes were not organised by the demos?

Also, perhaps that inevitable product of democracy, bureaucracy, is why this period of history is one with such relatively fine records. The importance of posterity was such that even the ignominy survives. Would a king or an oligarchy have been so transparent?

Ultimately the question must be one of self-determinism; were the ancient Athenians content to preside over the first functioning democracy the world has ever known?

Well, the fact that they made Democracy a goddess in the 4th century BC certainly suggests they had strong feelings towards its retention. As does the fact that they relinquished it so very reluctantly.

One can imagine that, when the Macedonians wrenched democracy away from the clawing grasp of the demos, tear-drops, much like the blood from the Tyrannicides’ blades would have salted and stained the terrain at the foot of the Acropolis.