By Ben Potter

Regular readers will recall our discussion on the dubious and debated identification of Homer i.e. was he one man or two? Was he a woman? Was he a school of poets and compilers?

Homer’s contemporary, the Boeotian Hesiod, if anything, is even more troublesome in this respect. Like with Homer, two poems are ascribed to Hesiod: Theogony and Works and Days.

N.B. A third, Shield of Heracles has been almost universally discredited as his work.

And (as with Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey) the prevailing point of debate is that a different man was responsible for each poem.

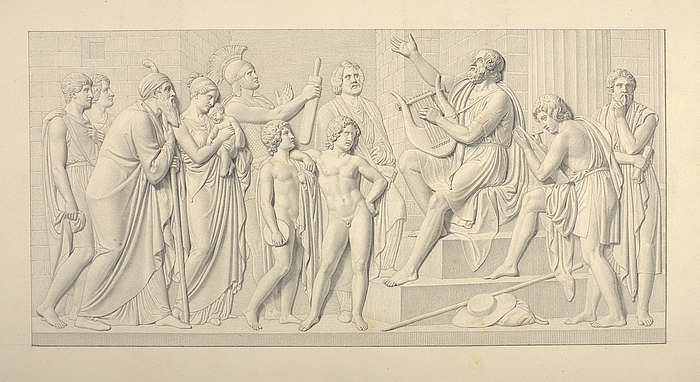

Hesiod and the Muse, by Moreau, Gustave, 1891

Interestingly, the main evidence for this is not the extremely different themes and tones, or the inability to date the works, but the fact that they vary significantly in quality.

Propagators of this idea claim the Theogony is laboured, stifled… often tedious in parts. To a lesser extent the same accusations have been levelled again the Iliad, i.e. that gods, catastrophes, sex, intrigue and violence rescue a text lacking in the pace and drive to do full justice to such subjects.

And, with the Theogony, comments about pace do not bemoan the lack of it, but the uniformity of it. In other words, there is too much high drama, too much repetition, too many and too frequent powerful adjectives. With no down time and no juxtaposition, there is no possibility for tension to build; all ebb, no flow.

Also, opportunities for toe-curling tension are wasted. Man’s genesis is ignored and long lists of names trudge along without passion, each as monochrome and forgettable as the last. Moreover, Zeus is so powerful and so perfect that we never fear for his position or safety.

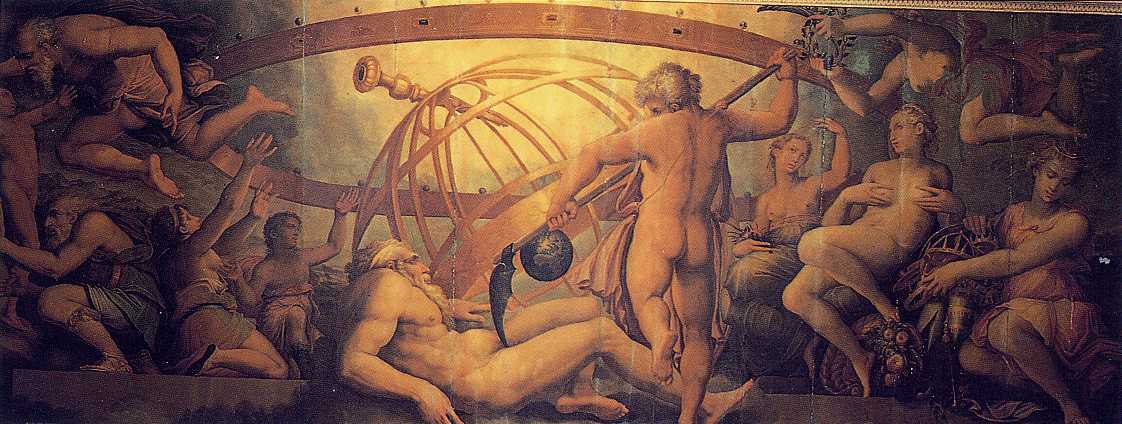

Regarding tension, take this example of Kronos castrating his father Uranus:

“The hidden boy stretched forth his left hand; in his right he took the great long jagged sickle; eagerly he harvested his father’s genitals and threw them off behind”.

Such pungent tragedy is given scant attention; Uranus loses his manhood without even a whimper of resistance, whilst the list of the offspring of Nereus and Doris lasts for 31 dreary lines!

However, these criticisms are asking for a different text; one like the

Iliad. If we take at face value that this is a work of religiosity (see the

Bible of Ancient Greece) then we can excuse certain dramatic shortcomings, much like the unendurable ‘begat…’ passages of the bible, or the sanitized and colourless

canti of Dante’s

Paradiso.

Additionally, we mustn’t forget that this is a poem designed to be sung to music. Therefore, there would have been some scope for understating or emphasising supplementary to the mere text.

Likewise, the musical aspect accounts for repetition. In this respect Homer is far more guilty than Hesiod, but understandably so. A repeated or ‘stock’ phrase would allow the performing bard time to gather his faculties before singing the next verse.

It should be stressed that the caveats above do not hope to diminish just how different Works and Days is from Theogony.

The former poem is a treatise on mythology, ethics, sailing, home-spun wisdom, superstition and, above all, farming.

It is a world away from the ethereal Theogony and its laudation of the practical, noble and wholesome unravels in a charming and, often, very amusing manner.

The poem is a long letter from Hesiod to his feckless and reckless brother, Perses.

In Works and Days Hesiod adopts the persona of, or actually really was, a curmudgeonly old son of the soil.

He comes across as…

- Puritanical and joyless: “your wife should have matured four years before, and marry in the fifth year. She should be a virgin; you must teach her sober ways”.

- Misogynistic: “Hermes the messenger put in [woman’s] breast lies and persuasive words and cunning ways”.

- Sanctimonious: “Oh foolish Perses, sailing in a ship because he longed for great prosperity”.

He’s also distrustful of city-folk, pleasure-seekers and dishonesty. But above all we recognise his industriousness, simplicity and innocence.

He is naïve, rural and quaint, bordering on twee.

If this really were a letter to an errant sibling, then one could imagine the response consisting of only two words; the second being ‘off’.

That’s not to say the advice is bad. Much of it gives an ignorant city-dweller (like myself) a pretty good rough guide to the mysteries of tilling the soil. Also, some of the more general and axiomatic fragments are heavy with sagacity.

Indeed, one can identify within the poem’s pages the inspiration for

Polonius’ famous speech in act I scene III of Hamlet: “Neither a borrower nor a lender be; for loan oft loses both itself and friend, and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry”.

However, the superstitious snippets are often risible: “don’t piss towards the sun” is one such unforgettable piece of counsel.

Despite this, it would take a debater of Ciceronian stature to make a decent case that Theogony were the better poem.

Works and Days has greater and more flexible poetical guile, a more judicious use of vocabulary, and more evocative comparisons and contrasts than Theogony.

That said, there are undeniable crossovers between the works.

The Muses of Mount Helicon are invoked at the beginning of Theogony and again in Works and Days. Even supporters of the ‘two-poets’ argument admit that this is no coincidence. However, the best argument justifying this is that Helicon was some sort of literary pilgrimage site; an artistic Lourdes.

If the Hesiod of the Theogony had been the first such divinely inspired bard then it’s perceivable that a ‘Hesiod school’ could have appeared with countless scribblers using his name.

Perhaps this straw-clutching explanation isn’t as farfetched as it sounds. After all, it’s widely assumed some of Aristotle’s work was written by his pupils and colleagues. The same goes for the works of many Renaissance painters.

It’s also been hypothesised that ‘Hesiod’ was an honorific given to the most able poet among his contemporaries. However, given by whom and how are questions uncomfortably sidestepped.

Suffice to say this ‘Dread Pirate Roberts’ idea holds about as much water as Tantalus drinks in a month.

Certainly such thinking, had it even been contemplated, would have been dismissed out of hand by the ancients. They didn’t merely think, but assumed both texts were the work of one man.

And though a majority of modern scholars argue for two poets, their numbers are partly outweighed by the leading cheerleader for a unified author; the exceptional American scholar,

Richmond Lattimore.Much like with the corresponding Homeric one, this is a debate which classicists love as there is hardly any evidence with which to make a refutation. What is more there’s nothing new likely to come to light and, providing there is always one dissenting voice, no chance of a resolution.

Something which does strike a note of concord is the assertion that Works and Days is a superb poem and Theogony is, at the very least, an extremely interesting one.

It may strike you that repudiating a two-and-a-half millennia old assertion that Hesiod wrote two poems simply because one is a better read than the other is a rather flimsy and extreme position to take. In such a respect you only have to think of your favourite author and compare their best to their worst book.

Luckily there is one way in which to reach a really satisfactory conclusion on the matter… but I’ll have to let you get on with that one yourself.