By Ben Potter

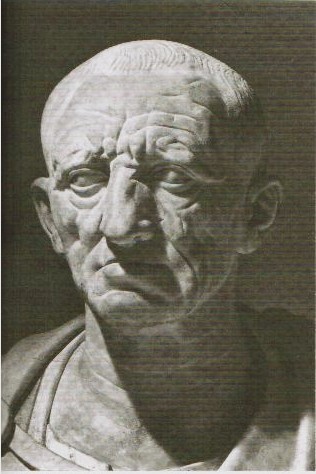

During his own era Marcus Porcius Cato (234-149 BC) was known as ‘Cato the Censor’, for his role in maintaining the census, supervising public morality, and overseeing certain aspects of the government’s finances. In times after, however, he was commonly referred to as ‘Cato the Elder’, in order to distinguish him from his great-grandson, the bane of Julius Caesar, ‘Cato the Younger’.

Whatever name he was called, Cato the Elder was an influential man, especially with regards to his writing.

As Cato was a politician far more than an author, his reputation as the de facto creator of Latin prose literature may not only have been a mere addendum to his true calling, but could also have been an unintended one.

It is not even clear if his Ad filium (to his son), De re militari (on military matters) and Carmen de moribus (hymn on morality) were intended for publication at all… though they enjoyed great fame after his death.

However, it is likely that he assumed his speeches would survive, though it’s unclear if he considered himself the father of oratory as a written discipline.

His only complete extant work seems to have been an extremely popular and influential one.

De agri cultura (on agriculture) deals with the practical and profitable management of an estate, rather than the nitty-gritty of seeds and soil. Additionally, he threw in a recipe or two, and seems to have had an almost unhealthy obsession with cabbage!

What is perhaps surprising is the clumsiness and disorganization of the work. This could be, however, a bi-product of writing during Latin’s literary infancy.

This leads us to mull over exactly why Cato wrote in Latin, as Greek, that ancient, sophisticated tongue, had been the accepted mode of prose for the Roman aristocracy for centuries.

One theory for this is that Cato was not really such a good student of Greek as a Roman aristocrat should be. However, it’s undeniable that he must have at least read Greek and been familiar with the great works of Athenian culture.

Another theory is that Cato was a novus homo, and, unlike the self-conscious and slightly sycophantic Cicero, he was openly proud of the fact. Thus, the use of Latin over Greek could have been seen as a poke in the eye to all the pomposity and pretentiousness of the senatorial classes.

The most likely reason, however, is that Cato’s private hatred of all things Greek spilled over into his literary life.

Cato believed that the Greeks were decadent, immoral, and generally inferior to what a good man should be, i.e. a Roman. Indeed, he considered most of the moral decay going on ‘these days’ a direct result of increased Hellenization.

John Briscoe elaborates:

‘In the Ad filium he called the Greeks a vile and unteachable race; in 155 BC, worried by the effect their lectures were having on Roman youth, he was anxious that an embassy of Athenian philosophers should leave Rome rapidly’.

Not that Cato’s spleen was uniquely vented Greek-wards; he had a similar contempt for, or at least fear of, the Carthaginians.

Here at least Cato’s xenophobia (a detestable Greek word!) was not quite so blind.

Carthage had been one of the biggest threats to Rome during the statesman’s time – with the brilliant general Hannibal very nearly changing irrevocably the balance of power in the Mediterranean.

It was, probably, for this reason that, late in life, Cato continuously petitioned the Senate to have the state of Carthage obliterated from the face of the Earth.

Champions of Cato have defended this catastrophic lobbying as the senile ramblings of an old man. Nevertheless, his words carried weight and, in 146 BC, three years after the old man’s death, Carthage was razed to the ground.

The counterweight to this, and indeed the reason why many still look on Cato with great fondness, is that such brutality, cruelty and inhumanity are at odds with his character in general.

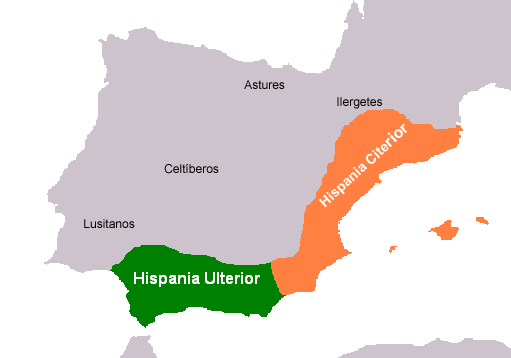

His detractors’ false accusations of ‘racism’ (a term which would have been meaningless in ancient Rome) fail to hold water. Indeed, possibly the most impressive accolade he received was from the people of Spain in 171 BC when they requested that he air their grievances to the Senate.

Despite his ruthless professionalism when in the province – he violently suppressed a revolt and sent a steady supply of gold and silver back to Rome – Cato had obviously impressed the locals with his integrity and diligence.

It was here that he had become famous for mucking in with the troops, personally overseeing menial tasks, sharing rations and generally leading by example.

Though this pandering to the common man would have done little to endear him to the pompous, ancient families of the Senate, they could not stand in the way of his Triumph – a military parade celebrating his achievements.

But much more than his vulgar sympathy for the great unwashed, what helped Cato make enemies were his morals and his mouth.

He was firmly against the repeal of the lex Oppia, emergency austerity measures that were obsolete in the wake of the booty accrued in the victory over Carthage.

In addition, he supported high levels of taxation on anything deemed to be a ‘luxury’.

He constantly chided the people’s darlings, the Scipios, for their lax military discipline and general ‘Hellenistic’ excesses.

Though despite all of this busy-bodying, it seems that Cato’s greatest problem was that he didn’t know when to keep his opinions to himself.

His curt and brusque nature offended and alienated many, not least the powerful and popular Marcus Fulvius Nobilior, the man who stole away

Cato’s literary protégé, the poet Ennius. He also kicked Lucius Flamininus out of the Senate.

As a general rule of thumb, if you can think of a famous name from the first half of the second century BC, Cato the Elder probably pissed him off.

Despite this, it was never in doubt that he was a man of conscience and true to his word. He initiated (or upheld) the lex Porcia, which allowed a condemned man to appeal directly to the people for justice.

Also, perhaps as a consequence of the high taxes on luxuries, he initiated a public building program which saw crumbling infrastructure renovated and the sewer system vastly improved.

He also seems to have been, with the glaring exception of Carthage, a broad-church isolationist.

Rome’s military interest in Rhodes and Macedonia were particularly distasteful to him for the simple and indubitable fact that such countries’ interests were none of Rome’s business.

Cato the Elder was in equal parts uncompromising, principled, obnoxious, arrogant, conscientious, frugal, tenacious, unwavering, loved, loathed and, above all else, patriotic.

Perhaps for these polarizing reasons commentators often don’t know where to place him in the pantheon of the great figures of antiquity – he has, with justification, been compared to as diverse figures as Jesus Christ, Ebenezer Scrooge and Ron Paul!

Indeed, Cato the Elder is one of those wonderful characters from the annals of the past who not only vividly come to life, but generate an emotional response.

And clearly there is plenty of ammunition for both his supporters and detractors to argue their respective corners. But on reflection, people in both camps tend come away with a similar feeling about this cantankerous and constant old git who said what he liked and liked what he said…

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.