By Ben Potter

Rome’s ‘Golden Age’ is, quite rightly, thought to have reached its zenith in the days when it was making the transition from the greatest Republic to the greatest Empire of the Ancient World.

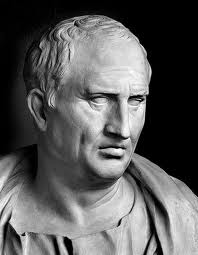

Such is the breadth and depth of interesting and talented artists and statesmen from this period – Julius Caesar, Augustus, Virgil, Horace and Livy are but the tip of this awe-inspiring iceberg – that Marcus Tullius Cicero can often end up playing a muted second fiddle.

Regular readers may feel an acute pang of deja vu as Cicero (106-43 BC) was blessed with that highest of high accolades a character from antiquity can hope to attain… he had a whole CWW newsletter all to himself!

Be that as it may, antiquity’s magnum man of letters had such a profound effect on political philosophy and the evolution of Western thought that he is worthy of another quick trot around the forum.

Though today we will not focus on his works, his consulship, or his exile and reinstatement, but on his role as governor of Cilicia in 51 BC.

This troublesome and affluent province consisted of a large chunk of the Middle-East, as well as the island of Cyprus.

This landmass, which today is so unruly, disputed and dangerous, was…. well… exactly the same in 51 BC.

Although the reasons for this were manifold, the key cause for Roman concern was the threat of the Parthians. Inhabitants of modern day Northern Iran, they had inflicted upon Rome one of the most humiliating defeats in her history, only two years earlier at the Battle of Carrhae.

Hence, Cicero was, to say the least, extremely reluctant to take up a post in which he would be required to secure the borders, suppress the barbarian mountain-folk, overhaul the administration, weed out corruption, encourage local participation, and keep taxes down… all while avoiding being massacred by the Parthians.

And so we must all stand agog to think that there was once-upon-a-time a politician who didn’t want a potentially lucrative and prestigious appointment. Not only that, an officeholder who accepted it anyway and managed to achieve all the demanding goals listed above.

Though what evidence do we have of Cicero’s reluctance to adopt the post? Well, we have it straight from the haughty horse’s mouth:

“I often blame my own unwisdom in not having found some way of escaping this job; it’s so hopelessly uncongenial to me”.

And this was before he even took up the position, when he was still en route in the comfort of Athens. Though clearly the affairs of state were already beginning to exert their pressure:

“Early days you may say, and point out that I am not yet in harness. Too true, and I expect there is worse to come… in my heart of hearts I am on thorns. Irritability, rudeness, every sort of stupidity and bad manners and arrogance both in word and act – one sees examples every day”.

Any suspicion of his protesting too much can be put out of our mind as Cicero had quite recently returned from exile. Consequently, he longed to remain at the hub of Senatorial politics, swaying and cajoling with his measured and miraculous oratory, rather than putting out fires at the edges of civilization.

Also, these lines are given greater veracity by the fact that they are taken from private correspondence between Cicero and his trusted and frugal friend, Atticus.

Indeed, much of what we know about Cicero; his credulity, passion, nobility, arrogance and the details of his political machinations come courtesy of letters to or from Atticus (and others) which were preserved and compiled by Cicero’s freedmen.

Such correspondences give us a chance to see the evolution of Cicero’s predisposition apropos the job at hand.

Even whilst still in transit his mood lightens considerably:

“Welcome reports are coming in, first of quiet from the Parthian quarter, second of the conclusion of the tax-farmers agreements, lastly of a military mutiny pacified by Appius”.

This is about the only good word Cicero has to say for Appius, his predecessor as governor who had left the province in such a dilapidated state. However, fair political news may not be the only reason for an upturn in Cicero’s mood. It seems the East was an excellent place for him to have his legendary ego massaged:

“Asia has given me a marvellous reception… I think that all my company are jealous for my good name”.

And perhaps because his welcome was so warm before he had even lifted a finger, or maybe because key issues seem to have been taken care of while his reign was in its infancy that Cicero took the Jeffersonian approach to governance.

There has been a suggestion that Cicero’s ‘small government’ line was simply out of apathy, that he let the province run itself because it was unworthy of his attention – Rome was politics, Cilicia a mere trifle.

While an interesting theory, this is highly unlikely.

Cicero was a dynamic, competent, energetic and honourable man who had more than a little regard for his reputation. Even though he may have resented his appointment, once in situ he seemed determined to be successful.

Of course, his and our idea of ‘hands on’ vs ‘hands off’ governance may have been slightly different. Many, if not most, Roman provincial governors were dynamic because they needed to be in order to feather their own nests. They were border-line autocratic and many used their power to become extremely wealthy; others were just drunk with power.

A perfect example of this is the governor Volesus who executed 300 people in a day and exclaimed with pleasure at the bloody sight: ‘Oh kingly deed!’

So although Cicero didn’t quite adhere the maxim ‘that government is best which governs least’, his dogma was perhaps closer to ‘that government is best which steals and massacres least’.

And though he may have been keen to downplay his role as a policy maker, he began to revel in his exciting new incarnation of commander-in-chief – a role for which the bookish Cicero never previously had much penchant nor panache.

Here we see Cicero at his most boastful, bragging and blatantly balderdash.

His letters home ooze faux-modesty when it comes to his role as a military man:

“We camped near Issus in the very spot where Alexander, a considerably better general than you or I, pitched his camp against Darius”.

“I received… from the army… this bauble of a title (imperator)”.

“I do not regard the honour (of a Triumph) as something to be unduly coveted”.

He fails to mention, however, that he had more than one helping hand in military accomplishments.

Despite disparaging his brother, Quintus, and fellow legate, Bibulus, as being inadequate to the post of command, both were, unlike Cicero, distinguished military men. Also, his ally in the region, Cassius, was instrumental in the successes for which Cicero takes credit.

Indeed, the most telling evidence which belies Cicero’s military credentials is the fact that he never actually engaged the Parthians in open combat.

The end of his Cilician duties were both a blessing and a curse to Rome’s great orator.

His return from his ‘second exile’ would precede, if not quite foreshadow, the civil war(s) to come. Twice in the coming decade Cicero would hitch his wagon to the wrong horse and suffer as a consequence.

Ironically, the first conflict, that between Julius Caesar and Pompey, could only take place because both men’s armies were idle – and idle because Cicero had left such (relatively) pacific conditions out East:

“If neither of the two goes off to the Parthian war, I see great quarrels ahead in which strength and steel will be the arbiters.”

So the two sides to Cicero, his vanity and arrogance on the one, and his loyalty to and belief in the Republic on the other, are brought into sharp focus at the time it mattered most; when the die had been well and truly cast.

He was given sagacious warnings by his friends concerning the impending strife; including this one from Caelius Rufus:

“It behoves a man to take the more respectable side so long as the struggle is political and not by force of arms; but when it comes to actual fighting he should choose the stronger, and reckon the safer course the better.”

However, Cicero heeded not these wise words and was ultimately prepared to put his own neck on the line rather than see the Republic fall without a fight.

His sacrifice was futile in all but one respect, it showed our supercilious and sanctimonious novus homo for what he really was, a man whose nobility came from within, who loved and respected the traditions upon which his society was built, and who could see the danger that the age of the dictators was ushering in…

…ultimately, and with the greatest of dignity, Marcus Tullius Cicero paid for his convictions with his life.

One comment

Awesome post.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.