Written by Tom G. Hamilton, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

As of this writing, news of the largest hoard of early Roman-era Celtic gold coins ever found— unearthed by a bird-watcher in Britain—are making headlines. The coins are reported to be Boudica-era gold “stater” Iceni coins. There is an understandable excitement all across the land, the front-page news making a change from the pandemic.

There is one symbol on the coins which pertains to Boudica’s story—and even points to her origin, which was not the British Isles.

That symbol—a horse—can help us discover who Boudica really was.

In ancient times, the Western Atlantic was well-established as home to the ancient Celtic peoples. This Atlantic cultural reality divided it from what is now “middle” Europe. The Celtic-from-the-West idea (John Koch/Barry Cunliffe) points us to the Iberian peninsula in the search for ancient Celtic roots. DNA study supports this. There was frequent movement and migration from Iberia to Britain, not just Celtic but also Phoenician. The Phoenicians, who had flourished in the Iberian peninsula since 1000BC, mined in Britain. They were a sea-faring people. They were cod-fishing in British waters before there was any Brexit to complicate fishing rights.

There were no nations, no frontiers, and no governments, just ancient Celtic tribal confederations who lived in lands bordered by rivers and mountain ranges, and within these confederations there were simple tribes or clans who lived for the most part in hillforts. It was one, homogenous, Western Atlantic homeland. Iberia was part of this reality.

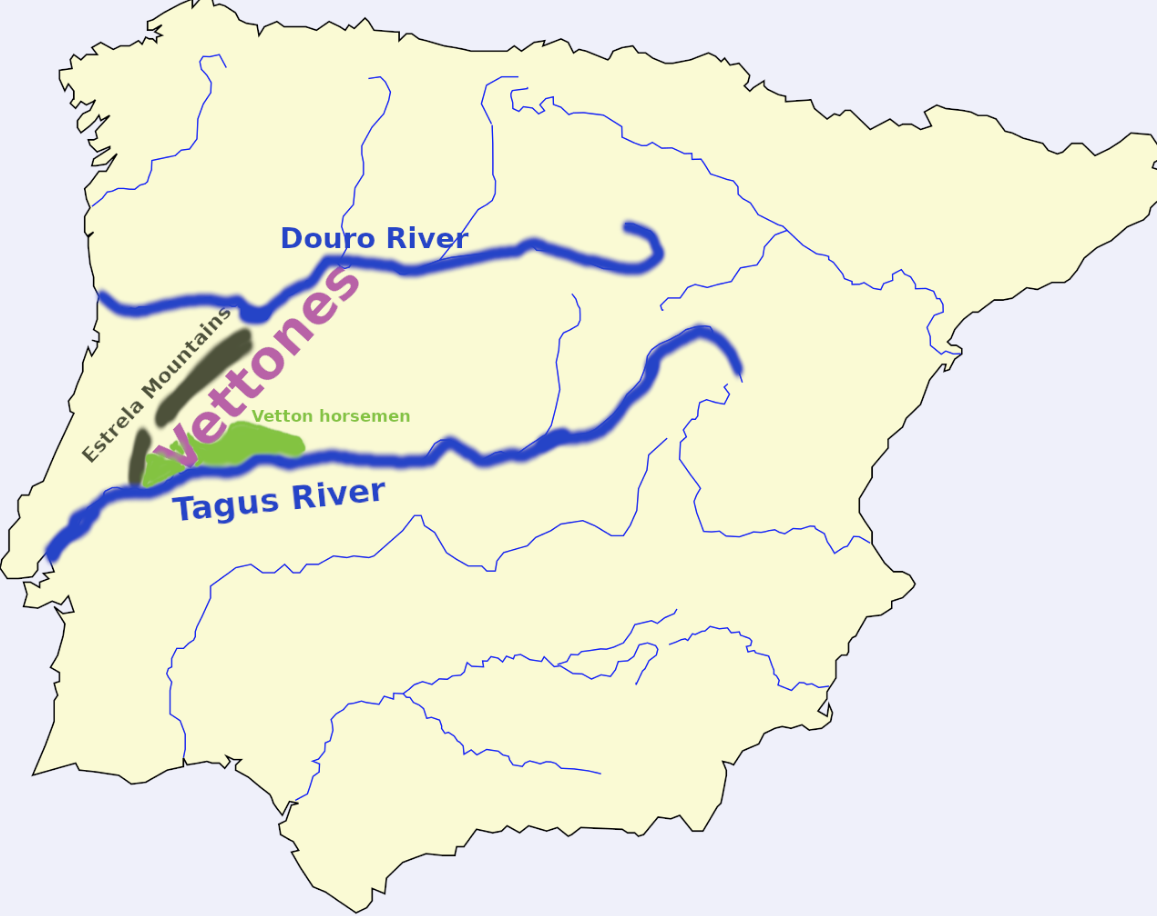

The Vettones were one such tribal confederation, living in the Iberian meseta between the Tagus (now Tejo) and Douro rivers.

The Vettones were known for being artistic and musical, but above all for being among the fiercest warrior tribes of Iberia. Also, the women fought alongside the men. West of their lands, spreading towards the Atlantic, lived the Lusitani.

Valiant Lusitani warriors such as Viriathu led the resistance against Roman occupation thanks to an alliance with their neighbors, the Vettons. It took the Romans 200 years to subdue this westerly, mountainous and hostile terrain.

Finally, tired of endless losses and exhausted by the guerilla-type warfare of the Lusitanian-Vetton alliance (also the embarrassing sight of their captured banners flying on the hilltops), the Romans became more aggressive.

In the end, it was only by trickery and deceit—and atrocities—that they subdued the western Iberian tribes, producing euphoria in the Roman senate in 150 BC. It was believed that at long last, they had finally conquered the Vettones.

This was the pre-history to the Roman invasion of Britain, without which we cannot properly understand it. Iberia provided Rome with everything. There were fertile lands for grain, wine and, especially, olive oil. There were also metals. The Romans set-up mega mining operations in areas previously used by the Phoenicians (whom the Romans persecuted because of Hannibal), taking vast quantities of silver, gold, copper, tin, iron and lead.

Area showing the “conhals” – huge piles of stones left by the Romans during massive gold mining exploration along the Tagus river.

Part of the Roman strategy was the systematic dismantling of the Celtic hillforts. This forced the Celtic clans down into the valleys below, where their spirits could be tamed and their whole mode of existence could be conditioned by the Roman ideals.

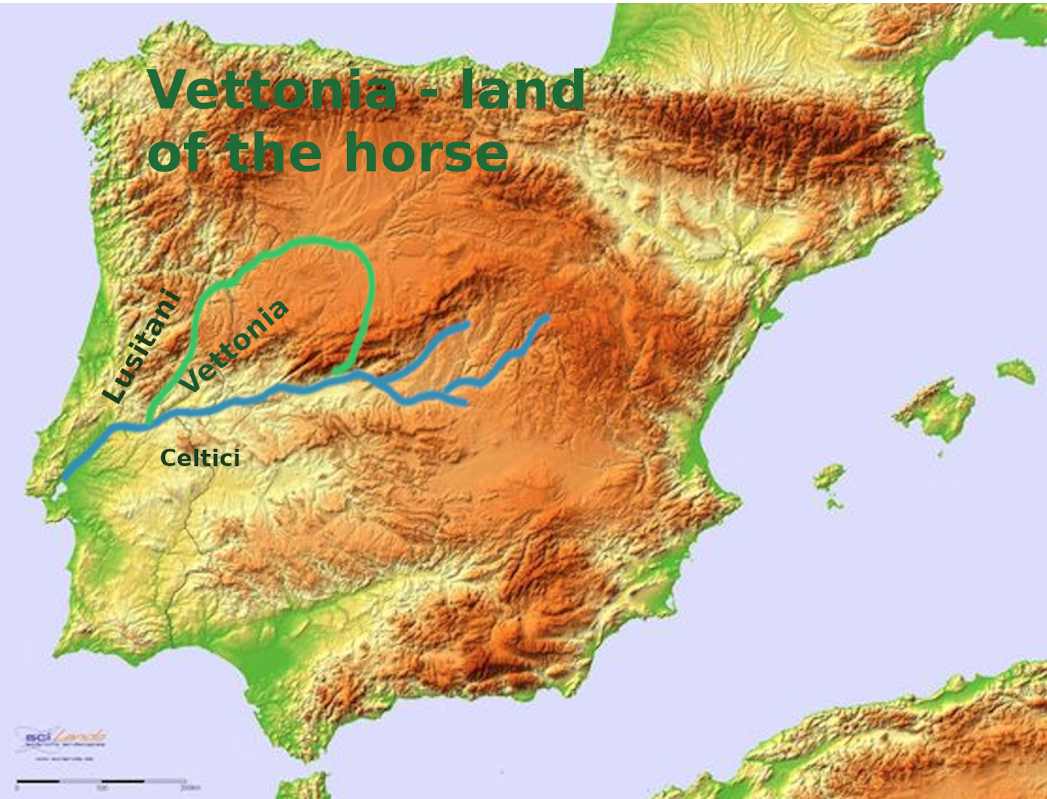

This inevitably meant re-organization, so Iberia was split up into regions. First they created Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior, then they created sub-regions, including their own Lusitania, which essentially amalgamated the Lusitani, Vettones and Celtici peoples. That was clever. Now the most valiant of peoples, the Vettones, would gradually forget their own customs and culture and become like the Roman role model, the Turdetani in the south. These, the Romans boasted, had embraced Roman ideals to the extent that they had even forgotten their own language. It was ethnic cleansing. The populations were decimated around the Tagus. Extensive gold mining used slave labour.

But the Vettones had something which was worth more than its weight in gold – horses. And the Vettones sure knew how to ride them. Even today in the small region of Beira Baixa, just north of the Tagus river, everyone can ride a horse. It’s just in the blood. Archaeologists marvel at the paleolithic horse drawings abundantly distributed in the river valleys of the Erges, Tejo, Ocreza, Coa and Zezere valleys.

The Lusitanian horse was bred (and still is) in the beautiful region just north of the Tagus. The Arabian horse is known for its speed, but the Lusitanian horse is famed for its courage and agility. The Vetton people had learned how to handle the horse over thousands of years, and they became expert and highly-feared warriors, carrying the severed heads of their enemies with them as trophies.

A Lusitanian horse. The horses are famed for their courage and agility. Note the long, curved neck and down-pointing head.

Previously headhunted by the great Hannibal Barca—key to famous victories like Cannae—the Romans weren’t the first to recognize the enormous potential of the Vetton horsemen. The Roman generals, including Julius Caesar, coveted their skills. So it was that the Alae Vettonum Hispanorum was formed–the Vetton Winged Cavalry. By offering them money, these valiant horsemen were tempted to leave their homeland and ally themselves with Rome in a bid for fame, fortune and adventure.

The Alae were first stationed in Germania, then Britain. They were among the first regiments to serve Rome in Britain under the Emperor Claudius in 43AD. However, it is possible some had returned with Caesar’s earlier, limited preliminary expedition.

Lusitanian horses are quite distinct and stand apart from their Arab horse cousins. This is true of their character as well as their appearance. However, it is not the short neck of the Arab horse with its sky-pointing tail that we see on the Iceni coins of Boudica’s reign, nor the Dartmoor ponies, but the long, curved neck and downward-pointing, slightly-curved head of the Lusitanian horse. It is unmistakable.

So, what is the Lusitanian horse doing on the Boudica-era coins?

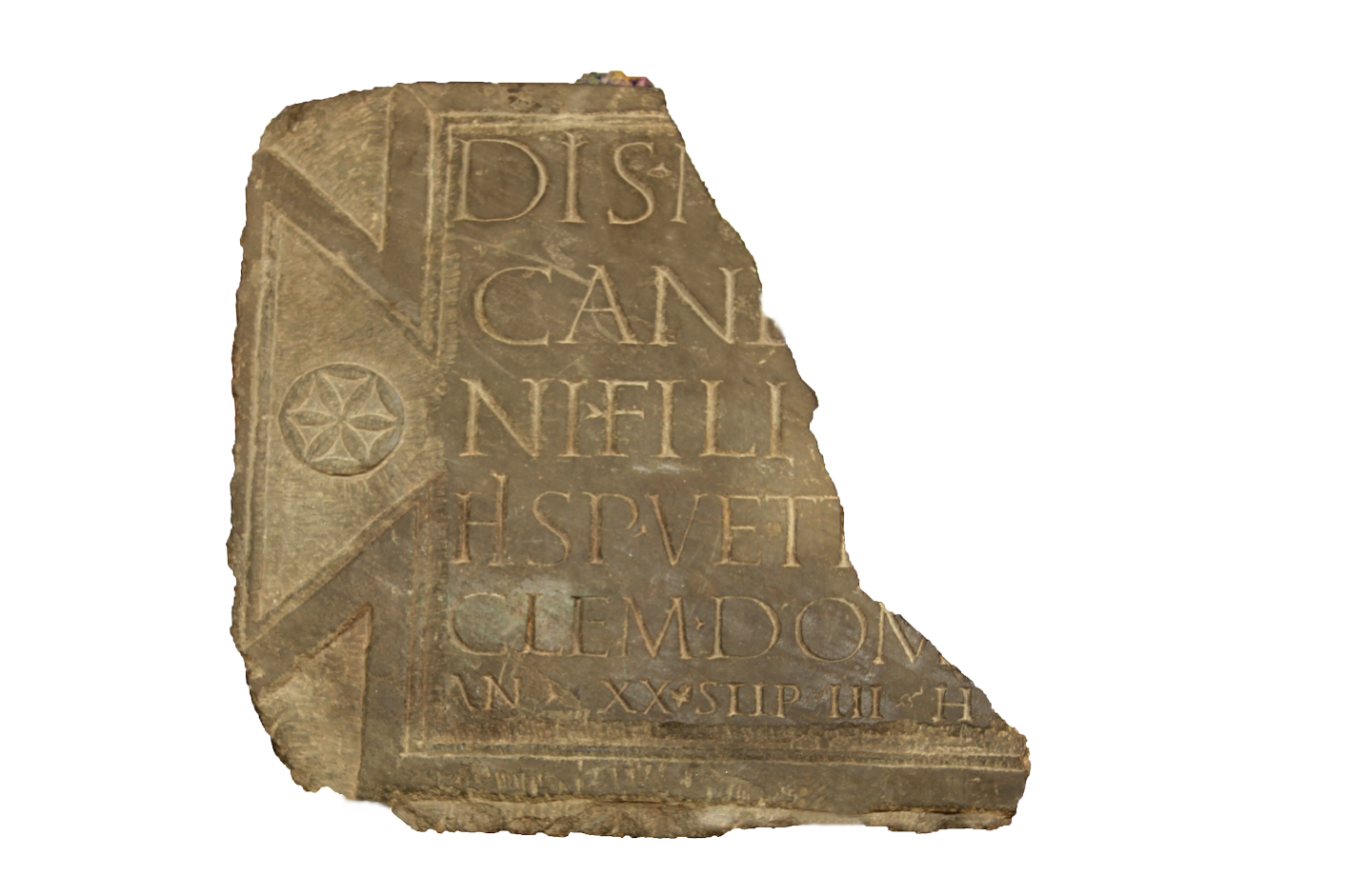

According to onomastic academic experts (who study the use of common names, history and etymology), Boudica’s name as written by the Latin writers was exclusive to the small region north of the Tagus river, known as Beira Baixa. This is precisely the place where the Alae Vettonum Hispanorum were formed. Three ancient stones dated to the first century era were found, each with Boudica’s name written on them, as transcribed by the Latin writers.

Map showing where the three first century stones with the name Boudica written on them in Latin text.

Can it be a coincidence, then, that her husband’s name is also linked to the region? For his name was not “Prasutagus”–this was a composite, a sort of nickname given by the Romans, which identified him as being their appointed governor over the Iceni people (Prasu–governor, Tagus–his Iberian name).

Boudica’s name, Tagus, the horses–all three indicate the small region in the interior of what is now Portugal for their origin. If they had been serving in the Roman cavalry, then that explains not only how they got to Britain, but also how they were promoted as governors of the Iceni and amassed wealth.

All was apparently going well until the despot Nero became Rome’s most powerful man. His excessive, riotous, extravagant lifestyle brought Rome to near bankruptcy. Nero introduced the 50% inheritance tax (which Tagus had adhered to, leaving half to Nero and half to his daughters), but then Nero upped it to 100%.

Boudica was flogged and her daughters raped because—the coin hoard find suggests—the “tax money” had been purposefully hidden. Humiliated but brought to her senses, Boudica revolted—the Vetton’s trust had been broken. She returned to her roots as a Celtic warrior, mounting her horse and leading a rebellion. At last, she’d seen through the thin facade of lies and deceit that were the promises offered by Rome.

As a special message to each emperor, first to Claudius, she took her army to Camulodunum (now Colchester) and destroyed the temple erected in his honor. Then she went to Londinium, the other main Roman colony, and graphically sent a message to Nero whom she derided as being effeminate and a bad musician.

To her, mother of two children, Nero and Rome had become mother-killers. Nero had killed his own mother in cold blood. So it was, in graphic detail, that Boudica took her famed Iberian sword, the Falcata, and had the breasts of the impaled noble women sewed to their mouths as a message to Nero. Motherhood was sacred to the Vettones, and Rome was bringing about its own downfall.

Today, Boudica’s statue stands next to the palace of Westminster, the houses of the British parliament. Although she was an Iberian woman, she is a cultural symbol of Britain. Her statue forever reminds us of her inseparable bond with horses.

While she was in revolt, in 60/61AD, Roman commander Suetonius had taken the Roman army to Wales to destroy the Druid stronghold in a radical move to ethnically-cleanse the Celtic memory, as they had done with the Phoenicians. As they were committing this genocidal atrocity, Boudica was coming to her senses, seeing through the false facade and illusion of cultural superiority that was Rome. At the time, Rome was all but an inch from abandoning Britain. That is why she will always be with us.

References:

Turdetani model Roman tribe: Strabo Geography book 3 . 2.140

Exclusivity of Boudica name to Beira Baixa: La onomástica personal prelatina en la antigua Lusitania, Salamanque , 1957 Palomar Lapesa, 1957, p. 63

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.