By Ben Potter, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

It is the eternal question for all classics enthusiasts: brawn versus brains, power versus beauty, empire versus empiricism – Rome versus Greece.

Which team do you support?

Which is better? Greece or Rome? Illustration of Ancient Athens

Of course the equation is far, far more complex than that. Indeed, most of the choices listed above are somewhere on the spectrum between ridiculously oversimplified or downright wrong; too false to even make a false dichotomy.

The Greek Roman Historian

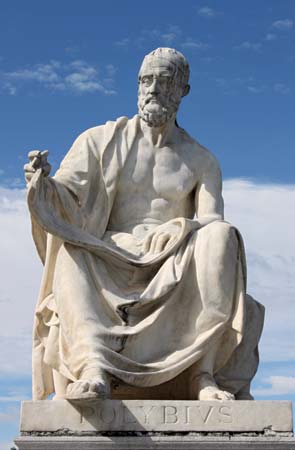

The stele of Kleitor depicting Polybius, Hellenistic art, 2nd century BC, Museum of Roman Civilization

Thus, Polybius gives us an intelligent outsider’s view of a budding young empire, one that was already making huge waves in the Mediterranean two centuries before the age of the Caesars.

But how did these waves occur? What tiny ripples set them in motion?

Well, Book VI of Polybius’ The Rise of the Roman Empire is devoted to explaining exactly how Rome became the world beater it was. Not through events (that is tackled elsewhere in his work), but through organization.

According to our historian, the only way for people to prosper in the ancient world was if they had a strong constitution… and Polybius idealized the Roman constitution.

The Robust Roman Constitution

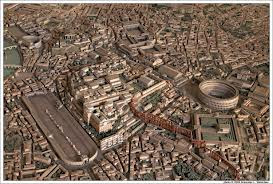

Ancient Rome, built on a strong constitution? Reconstruction of Ancient Rome

He thought it was optimal because it combined the three theoretically sound, but easily corruptible, systems of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. Together these became more than the sum of their parts and acted as checks and balances against one another, thus making sure no one body became predominant.

Moreover, each system, Polybius states, i

nevitably decays and devolves down the social ladder before completing a full cycle (i.e. monarchy becomes aristocracy which becomes democracy which becomes monarchy…). This governmental anacyclosis, or perpetual revolution, according to Polybius, is what made his countrymen inferior to his captors.

So what manifestation did these political pillars take?

Well, first let’s look at the aristocracy – the privileged, out-of-touch members of society who controlled all the wealth of the empire and were nigh on impossible to remove from power.

Yes, of course we’re talking about the heartbeat of Roman politics… the Senate!

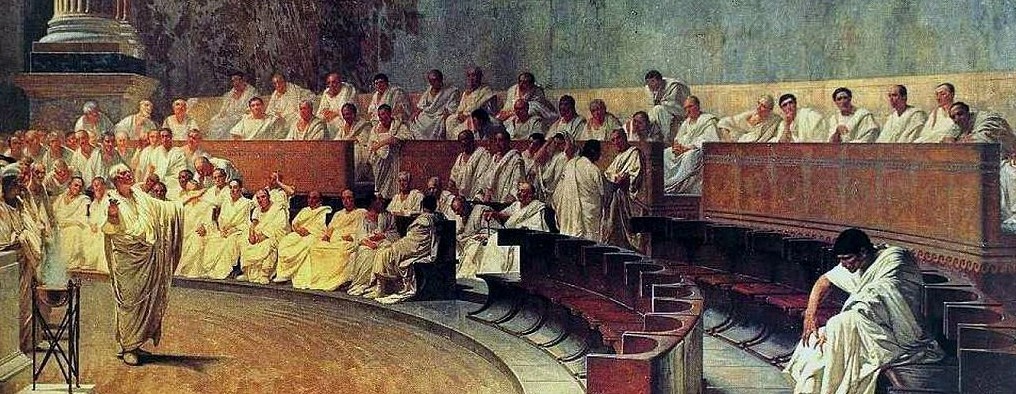

Cicero Denounces Catiline in the Roman Senate (1888), by Cesare Maccari

While Polybius propounds the virtue of a balanced system of government, nothing could have been further from the truth, because, in reality, the Senate held all the cards and, by and large, did whatever it wanted to do.

This included the monarchical arm of government, the Consuls, which were appointed by the Senate. Two men were chosen together on one-year terms to be the commanders-in-chief, as well as be responsible for the purse strings of the state. And strictly speaking, one was not eligible for the position of Consul unless he had completed the cursus honorum (path of honor), meaning he had already held every significant office of government.

Roman Drawing – Two Roman Consuls On Their Thrones by Mary Evans Picture Library

Thus, despite technically being a balanced, democratic government with a qualified and responsible head of state, Rome was de facto ruled by a self-interested and pernicious elite.

Such a thing is, of course, unimaginable to us now!

AntiFragile Constitution?

Polybius didn’t merely believe Rome’s constitution to be strong, but felt it was one able to withstand any disaster, one perfectly devised, and therefore eternally fit, for purpose.

And perhaps

the Roman constitution was ideal in Polybius’ day. Certainly there was sound reasoning behind his argument; he was no blind acolyte. Rome supremely dominated his known world and it must have been previously unimaginable that Greece/Macedon could ever be knocked off its lofty perch.

After all, the

tripartite constitution was borne out of the ashes of the fallible and inferior systems of the old world; Rome had learned the mistakes of its decaying predecessors. And with this knowledge it was ready to be the

caput canis for evermore.

However, Polybius could not have predicted Rome’s meteoric rise, its expansion in all directions, its resources and responsibilities, its supreme and unrivaled status.

Statue of Polybius, Vienna Parlimanet Austria.

Had he done so, then he may not have been so dogmatic in his assertion that the state’s current constitution determines its future strength; he may have conceded that, as nations evolve, so must the manner in which they are governed.

With the blessing of hindsight this is easy enough to say. Thankfully with such well-documented events readily available to anyone with the remotest curiosity in constitutional history, we can sleep safely in the knowledge that the present political arbiters will not commit the same folly of the Romans and needlessly shipwreck the state!

‘New’ World Allure

It’s easy to understand why Polybius wrote the way he did.

As an alien from the old world, the splendor and riches of a foreign country so much mightier than his homeland must have dazzled him.

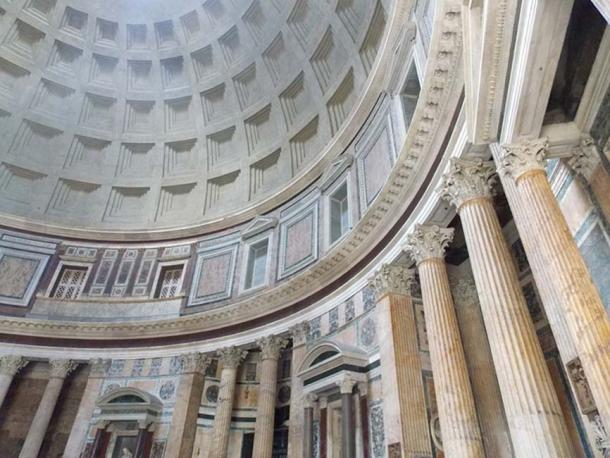

Rome’s Glory: The interior of the Pantheon in Rome, a concrete mausoleum with a beautiful dome and rows of columns.

And so, he simultaneously excused Greek inadequacies and explained his host’s dominance by the system of government the Romans employed.

It was the constitution that made Rome successful, he argued, and not fallible individuals, a disparity of natural resources or a more clement climate. And it certainly wasn’t the two most consistently important factors that have benefited states throughout all of history… timing and luck.

Rome Versus Greece

Book VI of Polybius’ history doesn’t merely talk about Rome’s superiority in governmental structure; the Greek armies also come in for plenty of criticism.

Polybius states that they were obsessed with using natural terrain, rather than discipline and tactics, as the default method of triumphing in battle. The reason being the Greeks were simply too lazy to build trenches or camps.

He also claims Greek bureaucrats were untrustworthy and corrupt when compared to their Roman counterparts.

Not that he puts this down to a weakness in the blood, but because Greeks (unlike Romans) were not sufficiently god-fearing.

He goes on to state that religion (literally ‘superstition’) stops the lower classes from behaving in a decadent and lawless manner. Despite his support for all things godly, he also believes that religion would not be necessary if all men were wise!

The lying in state of a body (prothesis) attended by family members, with the women ritually tearing their hair, depicted on a terracotta pinax by the Gela Painter, latter 6th century BC

Concurrent and parallel with the religious theme is one of ancestral devotion and public funerary rites, which was a great honor for a citizen.

During the ceremony a notable member of society read out the achievements of the deceased’s ancestors. This made diligent service to Rome not only a thing of civic and personal pride, but through these public funerals, a source of family pride as well.

For all these reasons, Polybius believed the Romans had achieved superior feats to the Greeks.

One comment

Great piece. No better opinion on Rome vs. Greece than from a firsthand perspective. We certainly lack spirituality in our “postmodern” culture,… and we’re trending in the wrong direction.

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.