Written by Mary Naples, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Thus, hard on the heels of the birth of her fifth child, Agrippa Posthumous, and still in mourning for her husband, the Princeps had his newly widowed daughter betrothed—this time to her stepbrother, Tiberius.

One can only imagine Livia’s delight. Finally, another Julio-Claudian union—the fervent hope must have been that it would be more fruitful than the last. Like Agrippa before him, everything was set except for one small detail: Tiberius was married.

In fact, Tiberius had been down this road with his stepfather eight years ago when, for purely political reasons yet again, Augustus married him to Vispania Agrippina (Agrippa’s eldest daughter with his first wife). According to Suetonius, in 11 BCE Tiberius divorced Vispania non sine magno angore animi (with great mental anguish). At last, the Princeps had been responsible for a union that resulted in love. Upon their heartbreaking divorce, an inconsolable and pregnant Vispania lost their second child.

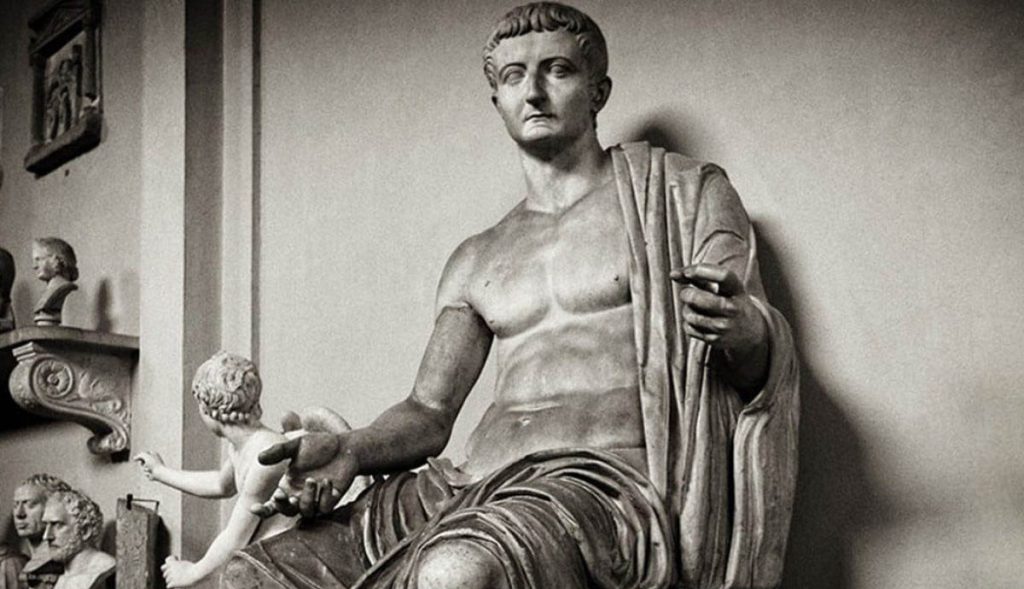

Seated Statue of Tiberius, 1st century A.D., Museo Chiaramonti of the Vatican Museum

Alas, the marriage of Julia and Tiberius had an inauspicious start. Raised in the Julio-Claudian palace more or less as brother and sister, rumor had it that the vivacious young Julia once had a crush on the solemn Tiberius. Those days long gone, initially they tried making a go of it resulting in Julia’s pregnancy. But theirs was not destined to be a happy union and the baby boy died in infancy. Shortly thereafter, injured fatally in a riding accident, Tiberius’s beloved younger brother Drusus died. For a man of his somber temperament, a grief-stricken Tiberius would not easily recover from the loss.

By this time, relations had broken down between the couple who found it difficult to live under the same roof much less in the same bed. Further, as a man who nursed his resentments, Tiberius felt slighted that the tender-aged heirs apparent—now his insolent stepsons—were increasingly promoted to consulships and distinguished priesthoods, while he, with an acclaimed military background, was relegated to diplomatic posts.

When Augustus offered him the tribunician power in the East, much to the dismay of the Princeps and the consternation of Livia, Tiberius flatly turned it down announcing he intended to “retire” from politics and move to the island of Rhodes. With a husband over fourteen hundred miles away, Julia was not content to stitch away the hours spinning and weaving as her conservative kin Livia and Octavia had done.

Livia and her son Tiberius, AD 14–19, from Paestum, National Archaeological Museum of Spain, Madrid

Making her vulnerable to the draconian marriage laws, she ran with a sophisticated crowd who viewed extramarital activities with nonchalance. She must have known the risks and appealed to her father for a divorce from her absent husband. But the Princeps would have none of it. As an eligible woman, the celebrated princess was a danger to the house of Augustus. With his successors waiting in the wings, the last thing the autocrat wanted was for an ambitious nobleman to jockey for political power, thus reducing the Princeps’ authority or that of his “own sons”—even though (or perhaps particularly because) they were truly Julia’s sons.

As a married woman with an absent husband, she was essentially an unmarried woman with no position in society. Even the cloistered Vestal Virgins would have been expected to have a more active public and social life than an unmarried woman. Required to live the life of a hermit, while being the life of the party, the extroverted thirty-something Roman darling was incapable of living in relative isolation—a simple fact a more attentive father would have known.

Then, in February of 2 BCE, the Princeps celebrated his twenty-fifth anniversary of “restoring the republic.” Amid much fanfare, Augustus was awarded the title of Pater Patriae (father of his country) and used the opportunity to promote his “own sons,” Gaius and Lucius as political heirs beginning a precedent for heritable rule.

It should be noted that, unlike his previous two sons-in-laws, Tiberius was not the Princeps’ political heir. In fact, after Tiberius’s self-exile to Rhodes, to a large extent, he was persona non grata at the house of Augustus and considered to be a threat to the successors should the Princeps die. Along those lines, to his imagined great humiliation, whether or not Tiberius should be allowed to return to Rome at all was now determined by none other than Gaius, his eighteen-year-old supercilious stepson.

Relief of Mars Ultor, 26–14 BCE; in the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Six months later, as propagandist extraordinaire, the Princeps threw another party to celebrate his reign. This time under the auspices of inaugurating the Forum of Augustus which housed the temple of Mars Ultor, an avenging military god founded by Augustus. The first of its kind, the edifice was dedicated to Roman nationalism and lined with statues of legendary Romans, singling out the Julian clan with notables such as: Aeneas, Romulus, Divus Julius (Divine Julius) and the headliner himself: Caesar Augustus.

Romans, always game for a party, were ostensibly celebrating twenty-five years of relative peace and uneven prosperity; a supposed golden era ushered in by the Princeps, who hailed as their father, Pater Patriaie. Yet, because of subsequent events that night, Augustus is less remembered as the father of Romans than he is as the father of Julia. After the revels had ended and the pageantry long faded, the Princeps was not yet done with his day. That night, he sent a letter of denunciation against his own daughter to the servile Senate.

3 comments

Shouldn’t that be heirs apparent?

Hallo there!

It seems that family life was a dangerous affair in the past for those who belong to society’s top classes (which were usually controlled by a few families)…

Cleopatra, a member of another dangerous family (Ptolemy), also comes to mind…

Thank you for the catch, Isaac!

Best,

Alex

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.