By Ben Potter, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Painting of Thucydides

What springs to mind when we think about literature of the Ancient World? Maybe it’s Homer’s Achilles dragging the corpse of Hector around Troy or Sophocles’ Oedipus stabbing out his polluted eyes. Perhaps it’s Plato’s Socrates holding forth or Herodotus’ Leonidas and his 300 Spartans. It even might be the dulcet tones of Sappho, the penetrating ones of Catullus, or the scathing superiority of Cicero.

Whilst the above mentioned epic poetry, theatrical drama, philosophical dialogue, historiography, romantic poetry, and private correspondence are all represented as well as appreciated, we give less thought to an area of literature that has never been more prevalent than it is in modern times.

It is the form of writing which is the savior for those wishing to buy lousy, last-minute Christmas presents; the biography.

Aristotle, by Jusepe de Ribera, 1637

The beginnings of this genre are both fragmentary and fractured, as the writers of biography have their smudgy thumbprints all across the literature of antiquity. Consequently, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly when ‘biography’ begins.

Odysseus and the Sirens, an 1891 painting by John William Waterhouse

Bust of Pericles

Not surprisingly, it took the interference of Aristotle to change the way biography was approached.

His views on ethics prompted the rethink that deed was no longer the be-all and end-all of a man’s life, his character was now worth more than a mere footnote.

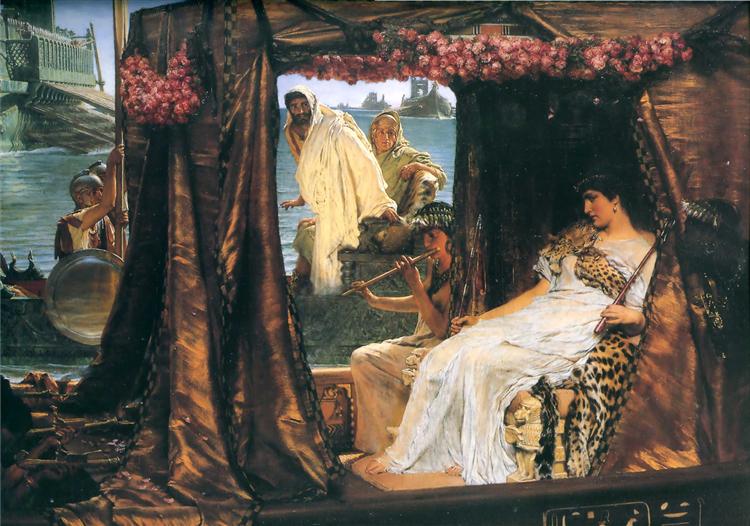

The reign of Alexander the Great, brief as it was (336-323 BC), was the next great catalyst which brought a spate of biographical works. Notably from Ptolemy I, the founder of the dynasty that would eventually (and incestuously)

spawn Antony’s Cleopatra.

Anthony and Cleopatra on the Nile by Lawrence Alma Tadema

Some biographers, such as Onesicritus, dealt with how Alexander was brought up, rather that his personality or accomplishments. Ptolemy, however, focused on Alexander, the man, more than his exploits. Furthermore, Ptolemy contributed to the field of biography beyond his scribblings, he also created an ethos of scholasticism, most notably by establishing the Royal Library of Alexandria.

Then there was the memoir, the most self-indulgent and vainglorious form of biography, which was also in existence (even if not prevalent) in the Greek world.

When Romans came to dominate the Mediterranean both artistically as well as militaristically, the biography became exultant and, very often, ‘auto’.

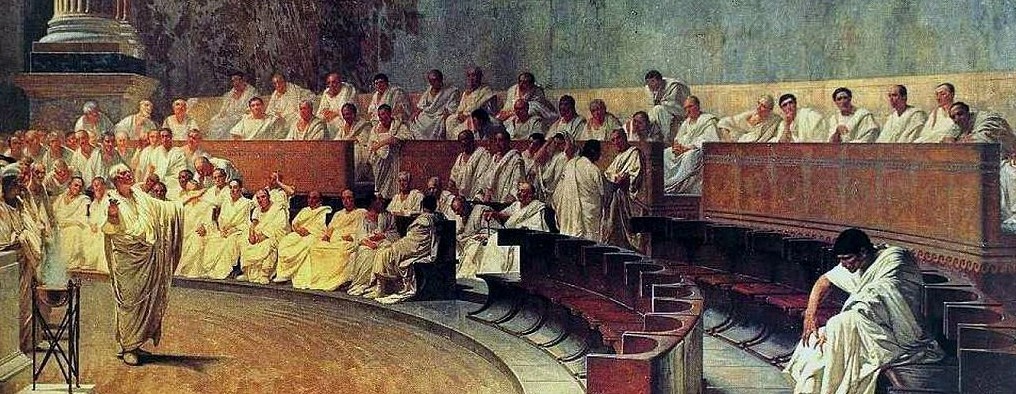

This is thought to have been due to the importance of family, specifically of the reflected glory of noble lineage – a preoccupation that went far beyond familial pride. A Roman’s self-worth was intrinsically linked to the glory of his forbears, a concept that never failed to irk the novus homo, Cicero.

Cicero Denounces Catiline (1888), by Cesare Maccari

The fact that Romans paraded busts of prominent ancestors at funerals shows how much stock they put in…. well, stock.

Indeed, the death of a family member was a wonderful opportunity to pompously self-promote. It could even be said that the distastefully elaborate and lengthy epitaphs from the time were a form of biography in themselves.

In general, biography became an exercise not only in curiosity or narcissism, but also in duty and career advancement.

Vercingetorix throws down his arms at the feet of Julius Caesar, by Lionel Royer

However, the precedent had been set, a tradition had begun. The emperors Augustus, Tiberius, Hadrian and Septimius Severus all wrote similar such books.

Marcus Aurelius, the great philosophical emperor, reached a zenith in this narrow field with his intellectually curious and stoic form of self-promotion. Indeed, it is thought there is nothing comparable to his introspection written by a native Latin.

It’s important to remember that in general, the biography was not merely a vehicle for glory, but for survival of both oneself and one’s state.

As the Republic was dying and the Empire forming, power seemed to be capriciously ebbing out of the hands of all those who briefly held it. With the stakes so unprecedentedly high, biography was used to defend, accuse, counter-accuse… it became the conduit, the desperate measure the desperate times required.

————————————-

P.S. The Other Biographers

You may be amazed that the above article could have discussed ancient biography without even alluding to the contributions of men like Theopompus, Timaeus, Plutarch, Josephus, Tacitus, Sulla and Sallust.

The truth is that each of these fine exemplars of the art could easily have devoured the author’s weekly word-count without so much as a “how do you do”.

That said, the one glaring omission who deserves special attention (even in the context of why he has been ignored) is Suetonius.

A fictitious representation of Suetonius from the 15th-century Nuremberg Chronicle

Dealing with the lives of the leaders of Rome from Julius Caesar up to Domition, it is a work truly worthy of scrutiny. Indeed, it could be said (though I’m sure not entirely without detractors) that, when it comes to the biography of antiquity, Suetonius is even more essential than he is elegant and enlightening.

Rather than use my own paltry words, I will borrow from the foremost expert in the field, Christopher Pelling of Christ Church College, Oxford. Here he explains the impact and importance that Suetonius had in highlighting the un-oscillating swing that had occurred in the higher echelons of Roman politics:

“The style of the Caesars proved congenial as spectators increasingly saw Roman history in terms of the ruling personality, and biography supplanted historiography as the dominant mode of record”.

And this style, twinned with the introspection and inquisitiveness of Marcus Aurelius, are the ingredients that go into many of the biographies flying off the shelves today.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.