Written by Brendan Heard, Author of the Decline and Fall of Western Art

The Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt is a unique reference point in classical history. Most notably, our very notion of classical wisdom itself largely depends on this period, insofar as it played a role in the documentation, preservation, and accumulation of the wisdom of the Greek world. It was a singular cultural epoch that sprang up into its own golden age, flourishing for a time, followed by rapid decline and acquiescence to Rome. Egypt was ruled for roughly three hundred years under Ptolemies (from 323 BC to 30 BC), ending with the death of Cleopatra.

As a civilization it was a relatively rare example of a largely tranquil symbiosis; where the philosophical ideas of a Greek ruling class took fertile root in an Egyptian culture—a culture already at that time considered impossibly ancient. The particular Ptolemaic world view which rooted and ripened in that immortal Nile valley soil gave classical history three hundred years of highly innovative, self-actuated, archaic-romantic civilization. The Greek rulers were as much influenced and altered by that eldritch land of ancient gods as the land was by them.

Most notably, this vibrant community led to the creation of the most important place of learning and wisdom in the ancient world. Perhaps ever. The much celebrated and lamented Library of Alexandria.

Its history began with the god-like Macedonian conqueror Alexander The Great, who overtook Egypt in 332 BC. He was regarded there as a liberator from the Persian oppression of the Achaemenid Empire (Artaxerxes III). Alexander was afterward crowned Pharaoh. To the Egyptians, pharaohs were the divine link between gods and men, who ascended to godhood in death. The Great Alexander, in turn, secured his own Egyptian godhood by consulting the Oracle of Siwa Oasis, who declared him a son of the god Ammon. From that point on, Alexander considered and referred to himself the son of Zeus-Ammon.

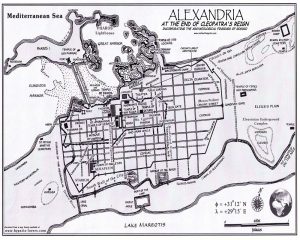

It is reported that Alexander, while dreaming, asked Ammon what he was to do. The god responded to him saying that his destiny in Egypt was to found an illustrious city at the site of the island of Pharos. This the great conqueror set forth to do, and this was henceforth to be named after him: the city of Alexandria.

But Alexander left Egypt before the city was built and never had a chance to return, dying soon after in 323 BC.

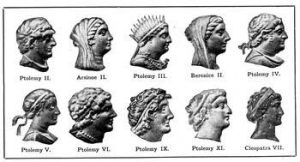

After his death, one of Alexander’s somatophylakes, the historian Ptolemy, was appointed satrap of Egypt. Soon after he declared himself pharaoh Ptolemy Soter I (soter meaning saviour). Ptolemy and his descendants adopted Egyptian customs, including religion, and had themselves portrayed sculpturally in Egyptian style. They built magnificent new temples in honor of ancient Egyptian deities and adopted the monarchic system of dynastic pharaohs. This was not unusual, as the Greeks from the onset had revered Egypt and its magnificent longevity, and within a hundred years they had developed a new Greco-Egyptian educated middle class.

Ptolemy I Soter also went so far as to create new gods in order to unite his plural populace. Serapis was one such God, a combination of two Egyptian gods: Apis and Osiris. Additionally, Serapis combined elements of the main Greek gods: Zeus, Hades, Asklepios, Dionysos, and Helios, as well as influence from many other cults. Serapis had powers over fertility, the sun, funerary rites, and medicine, and included the worship of the new Ptolemaic line of pharaohs. To him they built the enormous Serapeum of Alexandria. Ptolemy I also promoted the cult of the deified Alexander, who became the state god of the Ptolemaic kingdom. This was a time when mortal men of sufficient influence really could become gods. Also in homage to the aims of Alexander, Ptolemy soon proclaimed the port city of Alexandria as the new capital of Egypt.

Fortunately, Ptolemy’s desire was to continue the work of his former master, which was to spread Hellenistic culture and Greek wisdom concepts throughout the known world. Where the Greeks had conquered, gymnasiums and libraries were erected. And libraries in particular enhanced a city’s reputation, attracted scholars, and augmented the available intellectual assets of a kingdom.

Any kingdom or nation faces threats to its existence. For Ptolemy the primary hazard came from his former comrades, the somatophylakes of Alexander who themselves had been granted rulers of surrounding satrapies. Each new kingdom which sprung up in the wake of one of the world’s greatest conquerors were thus set in competition against one other.

Coin of Balacrus, somatophylakes of Alexander, as Satrap of Cilicia, with letter “B” next to the shield, standing for B[AΛAKPOI].

Luckily for us, this rivalry often manifested itself in competitive feats of wealth and grandeur, of which exhibition of genuine culture was a token of magnificence. A kind of cold-war high-culture-race was underway: to have the largest or most impressive edifice, the most athletic and intellectual populace, to produce the greatest genius, artist, or astronomer, the most ground breaking scientific theory or understanding of archaic mystic philosophy. These were the conditions under which the Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy sought to make Alexandria an unrivaled center of knowledge and learning, and began plans (actual construction was likely begun under Ptolemy II) of the great Library. The construction of which was possibly managed by Demetrius of Phalerum, a student of Aristotle. Ptolemy sought nothing less than a repository of all knowledge, and his library would prove to be unprecedented in scope and scale, one that has gone unrivaled over the ages.

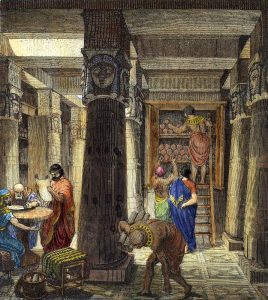

The library was not merely the largest collection of books (scrolls) in antiquity, but was also a kind of think tank, a research institution lavishly funded by the pharaoh. The actual library was housed within a larger building, known as the Mouseion (origin of our word museum), dedicated to the nine Greek goddesses of the arts, the Muses. Written research was officially conducted in both Egyptian and Greek. Scholars from across the Greek world and beyond were sought after and invited to live at the library, to practice their science, to teach, and to learn from each other, without domestic distractions. The first-century BC Greek geographer Strabo wrote that scholars were provided with a large salary, free food, lodging, and exemption from taxes.

It was a state-funded elite study group, only with the added advantage of not being invested in consolidating state power. The Greek scholars made no contribution to the economy. The aim of the library was nothing less than the virtuous pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. A place where scholars could come together and exchange ideas. Isolationist Egyptian temples had historically contained libraries but the books were kept largely secret from the public. Yet the combination of the Greek attitude toward philosophy and the impossibly ancient and staid nature of Egypt, served to abet the pursuit of new knowledge.

In characteristically Greek fashion, the collecting of scrolls itself became an idealized vocation, a paramount obsession. Visitors to Alexandria arrived with their versions of famous literary texts, while agents were sent abroad collecting everything they could find. Books became a kind of currency, and in terms of this wealth, the library of Alexandria became the largest collection in antiquity. Some estimates suggest the number was as high as 700,000 scrolls, which were not just stored but used for reference and research by the active scholars. These scholars then spent time copying and spreading this accumulated knowledge further across the Greek world and beyond, and it is to this effect that we can thank our own surviving awareness of Classical wisdom. Because of this, Alexandria became the symbolic brain of a scattered and oppositional ancient world.

The feats of scholarship soon began to gain notoriety and, as visitors increased, so did reputation. There may have been up to fifty learned men in the community, teaching and interacting at one time. Completely free from daily material burdens to indulge their intellectual pursuits. There were lecture halls, dormitories, and cafeterias, all enmeshed and linked in a manner to encourage the various experts of different disciplines to interact. There was a large communal dining hall, meeting rooms, reading rooms, gardens, lecture halls, and a great hall for the scrolls known as bibliothekai. It is speculated that the Mouseion may have also had a zoo for exotic animals. There was certainly a medical school where animals were used in the research of human anatomy (using human bodies was forbidden in the wider Greek world). Later, the library scholar Herophalus performed medical exams on dead human bodies, elevating the science of anatomy. Herophalus’ sacrilege was tolerated because the Egyptian embalming tradition gradually influenced Ptolemaic Greeks towards a more relaxed view regarding human dissection. Again, we note the creative virility of the symbiotic relationship of two quite different cultures, existing stably, mutually influencing one another.

Of the many poets who resided at the library, there were three of great fame for masters of Hellenistic verse: Callimachus, Apollonius of Rhodes, and Theocritus. Of astronomers there is Hipparchus, who figured out the path of stars, and length of solar years while in Alexandria. Eratosthanes figured out the circumference of the earth while studying there, by examining the length of cast shadows at certain times of day about sun-drenched Alexandria. He calculated this to an accuracy within 200 miles. The astronomer Aristarchus devised the first heliocentric model of the solar system (the known universe). Later, the Mouseion-educated mathematician and astronomer, Claudius Ptolemy (no relation), wrote his three influential treatises on astronomy, geography and astrology. Developing what we famously know today as the Ptolemaic system of astronomy.

An illustration of Ptolemy holding a cross-staff, published in Les vrais portraits et vies des hommes illustres (1584). Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS.

Overall, Alexandrian research was strongly centered towards mathematics. Among mathematicians under Ptolemaic patronage the most famous was the inventor Archimedes (inventor of the Archimedes screw), the polymath Eratosthenes, and the greatest geometer of all time, Euclid. After studying at the library of Alexandria, Euclid published his great text, The Elements, that immediately surpassed all previous geometric literature to that date and remains the foundation of that science today. It was Euclid’s access to the bibliothekai that allowed him to codify the collected results of basic theorems postulated by others through the centuries. Legend has it that when Euclid showed his work to the pharaoh, he was asked if there was any shortcut to understanding his work, to which Euclid replied, “there is no royal road to geometry.”

Along with poetry and mathematics, matters of philosophy and religion were treated with equal reverence, study, and proselytism. Many ancient texts became at this point translated into Greek, including the Septuagint translation of the bible, which made the story accessible to others. This is the primary Greek translation of the Old Testament, also known as the Greek Old Testament. Again, this work was done purely out of intellectual interest…to catalogue, examine, and learn from all available ancient sources.

In this sense the pagan world view had its advantages, in its ability to honestly assess other religions without offending its own dogmas, in a way that monotheism historically has not. These combined efforts to know all things in a spiritual context of understanding, united disciplines such as poetic literature and mathematics in common purpose, which we today might find unusual. They did not seem to share our quandary over the division of physical and metaphysical, or materialistic and spiritual. Astronomy and astrology were equally venerated, even if the latter was more open to interpretation, or understood to be spiritually speculative. Very seldom, if at all, in the ancient world do we see overt supplications to atheism or hard materialism. And that is despite it being a world where the gods changed with the generations, and the good ones became evil, and vice versa, and new kings invented new gods altogether.

All the studied disciplines at Alexandria, from anatomy to Platonism to topography, were interwoven in a tapestry of mutually educative striving, beneath the hierarchy of the Pharaonic society. The monarchic system itself, quite alien to us now, was also woven into this mesh as the unquestionable order, the foundational bedrock supporting the pursuit of high culture. We are reminded of these more esoteric and archaic foundations in the name Alexandria itself. For let us not forget, the city was named after the great godking Alexander, who created it, and all that followed, upon the basis of a dream-vision.

Concerning philosophy and mysticism more specifically, Alexandria nourished Neo-Pythagoreanism, Middle Platonism, Neoplatonism, Theurgy, and Gnosticism, which all flourished and were studied and transcribed by busy scholars under patronage of the Ptolemies over the centuries. In the name of these mystic and rational philosophies, and to the copying of scribes, and to the boundless ideas therein represented, we may also pay our respects to the memory of this golden classical city.

Abstractly speaking, the library, acting as a storehouse of philosophy, religions, history, and science, secured beyond its finite physical existence its sacred purpose: the dissemination and preservation of knowledge across distance and time. Many manuscripts that were ancient in Ptolemy’s day survive down to us thanks to the care of the various scholars that visited and lived in Alexandria. In this way the historic reverberations of the library issue about recorded history like ripples upon the surface of water—reaching ever outward.

The decline and fall of this institution was synonymous with that of the Ptolemies themselves. The precise cause of destruction is lost to time amid conflicting reports, and is often a controversial subject, beginning with the rise of Rome in that region.

Roman interest in Egypt was typically due to the reliable delivery of grain to the city of Rome. To this end the Roman administration made no essential change to the Ptolemaic system of government, however they were in all but name subjugated before the powerful new empire. The Romans, like the Ptolemies, respected and protected Egyptian religion and customs, although the cult of the Roman state and of the Emperor was gradually introduced. The great library was at least in part burned accidentally by Julius Caesar in 48 BC. But there are accounts of its existence by notable visitors who accessed its resources around 20 BC. However, overall, it dwindled during the roman period, and suffered from a lack of funding after the Ptolemaic dynasty ended with the death of Cleopatra.

Around 270 AD the library may have been destroyed further in a rebellion. By 400 AD paganism was outlawed and the Serapeum was demolished by Christians under orders from pope Theophilus of Alexandria. However, it may not have housed many books at that time, and was primarily a meeting place for Neo-Platonist philosophers following Iamblichus. In 616 AD the Persians conquered, and this was followed in the same century by Arab conquest, and whatever remained then of the library was finally destroyed for good in their sacking of the city by the order of Caliph Omar.

Whatever had remained of the collection at that point was no doubt finally lost. But as all things have a finite material existence, so do they also contain within them a portion which belongs to the infinite.

That virtuous intellectual Platonic Form, which the library of Alexandria was in imitation of, lives on eternally.

Which is the true posterity of the Ptolemaic project: namely the accumulation of ancient texts, the widespread theorizing and practice of new knowledge based on them, and the respectful patronage for thinking as a vocation. These virtuous ideas did not die out, but seeded future incarnations.

The Eternal City was Written by Brendan Heard, Author of the Decline and Fall of Western Art

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.