By Ben Potter

Much time and care is taken to bring the ancients to life; to imbue modern society with the idea that they were just like us in all their goodness and evil, their intoxication and sobriety, their love and lust, as well as their hate and chastity.

To downplay this would be both false and feckless, as well as an insult to a common humanity, evidenced by timeless art, extraordinary literature and the evocative tales found therein.

Nevertheless, there appears to be a sizeable exception, one in which the madness may be the same, but the method is barely recognisable… and that is religion.

The polytheistic panoply atop Mount Olympus and in the heaving halls of Hades have great range and romance, but, almost inevitably, very little for citizens of secular or traditionally monotheistic societies to empathize with.

True, there are familiar elements: virgin births, resurrections, fratricide, patricide and capricious cruelty. However, such moments merely serve to punctuate, and therefore reinforce, the strangeness.

One explanation for the disconnect lies not in innate practical differences, but in the lack of a codified text. In other words, there’s no Ancient Greek bible.

Or is there?

Well… No, there isn’t.

But at any rate, if one wished to make a case for such a thing then there is really only one contender; Hesiod’s Theogony.

Hesiod, from Boeotia on the Greek mainland, was a contemporary of the Near Eastern Homer – dating him to the 8th century BC.

Homer’s epic and upper-class material far outstretched the pious, practical and homespun efforts of Hesiod, but despite their stylistic differences, their fame grew in parallel.

(That’s not to say Hesiod was a down to earth poet of the people, the language he used was still elevated and rarefied.)

A near-contemporary myth, discredited even in antiquity, stated that Hesiod beat Homer in a singing contest. Although palpably untrue, the fact that the two men were mentioned in the same breath says something about Hesiod’s stature.

Additional ‘biographical’ information reports that he adulterously impregnated his host’s sister and fathered with her the Locrian poet Stesichorus. In revenge, he was thrown from a boat into the sea, only to be rescued and brought back to shore by a pod of philanthropic dolphins.

Such pleasant nonsense is first seen in the writings of Thucydides, three centuries after the fact. And, whilst telling us nothing of his life, such resonance does confirm that his legacy was almost as important as Homer’s.

So what of Hesiod’s epic piece, the Theogony? Is there any case to make for a polytheistic bible?

Well, not quite. It does not lay down doctrinal law, give advice on genital grooming, recommend who and how to love, or tut-tut at your choice of pizza topping. It does, however, give a pretty comprehensive list of gods, how they came to be, some of their key attributes, with whom they fought and with whom they… ahem… loved.

So if your definition of a holy book is one that outlines the origin and nature of gods, then the Theogony certainly qualifies.

However, we aren’t exactly dealing with a text of unalloyed veneration. Theogony is a warts-and-all account. There is no sugar-coating of the incest, murder, back-stabbing, cannibalism and madness that the Gods indulged in. Homer, to a far, far greater extent either humanizes, condones or simply ignores Divine guilt.

Something else which lends weight to the holy text debate is the fact that the various wars, affairs, births and castrations of the Theogony are almost certainly not a product of Hesiod’s fertile imagination. He, like Homer, was either chronicling or playing with established stories and themes.

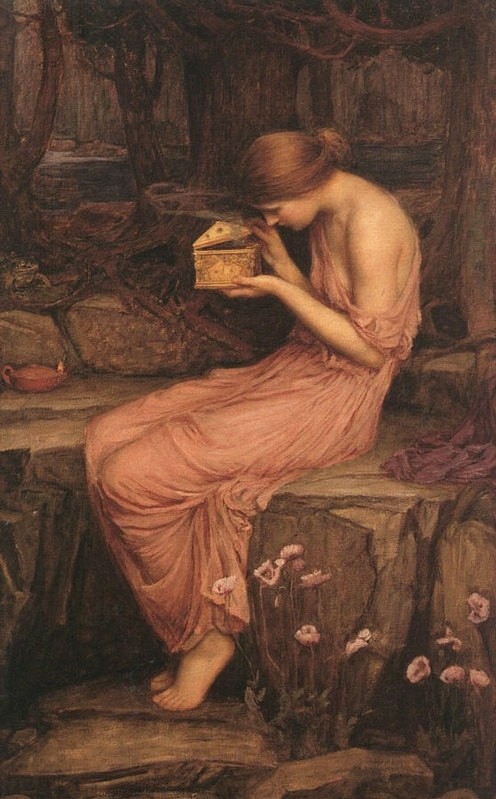

It’s been suggested that Hesiod’s material can be traced back to the mythology and pantheon of the Babylonians, however, any similarities here could be purely coincidental. After all, the Incas had a story unerringly similar to that of Pandora’s box!

But what does Hesiod teach us?

For starters, we are supplied with the origins of the ancient sacraments, which were an offshoot of Prometheus deceitfully serving some rather bony beef to Zeus:

“[Zeus] took the fatted portion in his hands and raged within, and anger seized his heart to see the trick, the white bones of the ox. And from this time the tribes of men on earth burn, on the smoking altars, white ox-bones”.

Moreover, we are precisely told our distance away from our Divine keepers, provided we know how big an anvil is and have a working knowledge of physics (which, alas, I don’t – write in if you do!):

“An anvil made of bronze, falling from heaven, would fall nine nights and days, and on the tenth would reach the earth; and if the anvil fell from earth, would fall again nine nights and days and come to Tartarus upon the tenth”.

In addition to the origins of creation, sacrifice, the wars that shaped the universe and a travel guide to heaven, Hesiod’s work supplies us with some charming etymological snippets – some thought to have been coined by the poet himself.

For instance, Cyclops is round-eyed, not one-eyed, as it comes from the Greek, kuklos (circle). Aphros (foam) refers to the birth of Aphrodite, who was issued from the foam congealing around the discarded testicles of the castrated Uranus. Most pleasantly of all, Hesiod tell us the Titans are called so because of the teino (strain) of their insolence. This makes phrases like ‘a titanic struggle’ or ‘a clash of the titans’ near-tautologies.

Indeed, there is much to be learnt about Greek, polytheistic culture from the pages of Hesiod. However, anybody who seriously makes the ‘bible’ argument is most probably guilty of retrospectively interpolating our current societal fundamentals into Ancient Greece…

Hesiod (and even more so Homer) is far more akin to Dante or Milton i.e. (presumably) pious, with a god-given talent and a god-thirsty audience.

However you wish to view Hesiod, as prophet, poet, public servant, or even some combination of the three, his work has stood the test of so much time that it almost boggles belief.

And why is this? Well.. I’ll leave it to the man himself to explain:

“When a man has sorrow newly on his mind and grieves until his heart is parched within, if a bard, the servant of the Muses, sings the glorious deeds the men of old performed, and hymns the blessed ones, Olympian gods, at once that man forgets his heavy heart, and has no memory of any grief, so quick the Muses’ gift diverts his mind.”

One comment

Seeing your emails in my inbox always brings a smile to my face.I always learn something from Classical Wisdom Weekly. Today I have to disagree with you regarding the Ancient religion. I don’t believe modern society is that different. They had their gods and their demi-gods, we have a god, prophets, saints, angels, seraphim cherubim. As they chose the gods they worshipped from their pantheon, we choose to honour the saints or prophets or angels that resonate with us. My immediate perspective is as an Eastern Orthodox Christian however this can be said of other denominations of Christianity as well as Buddhists and Hindu worshippers who venerate different manifestations of their prophets or gods.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.