by Sean Kelly, Managing Editor, Classical Wisdom

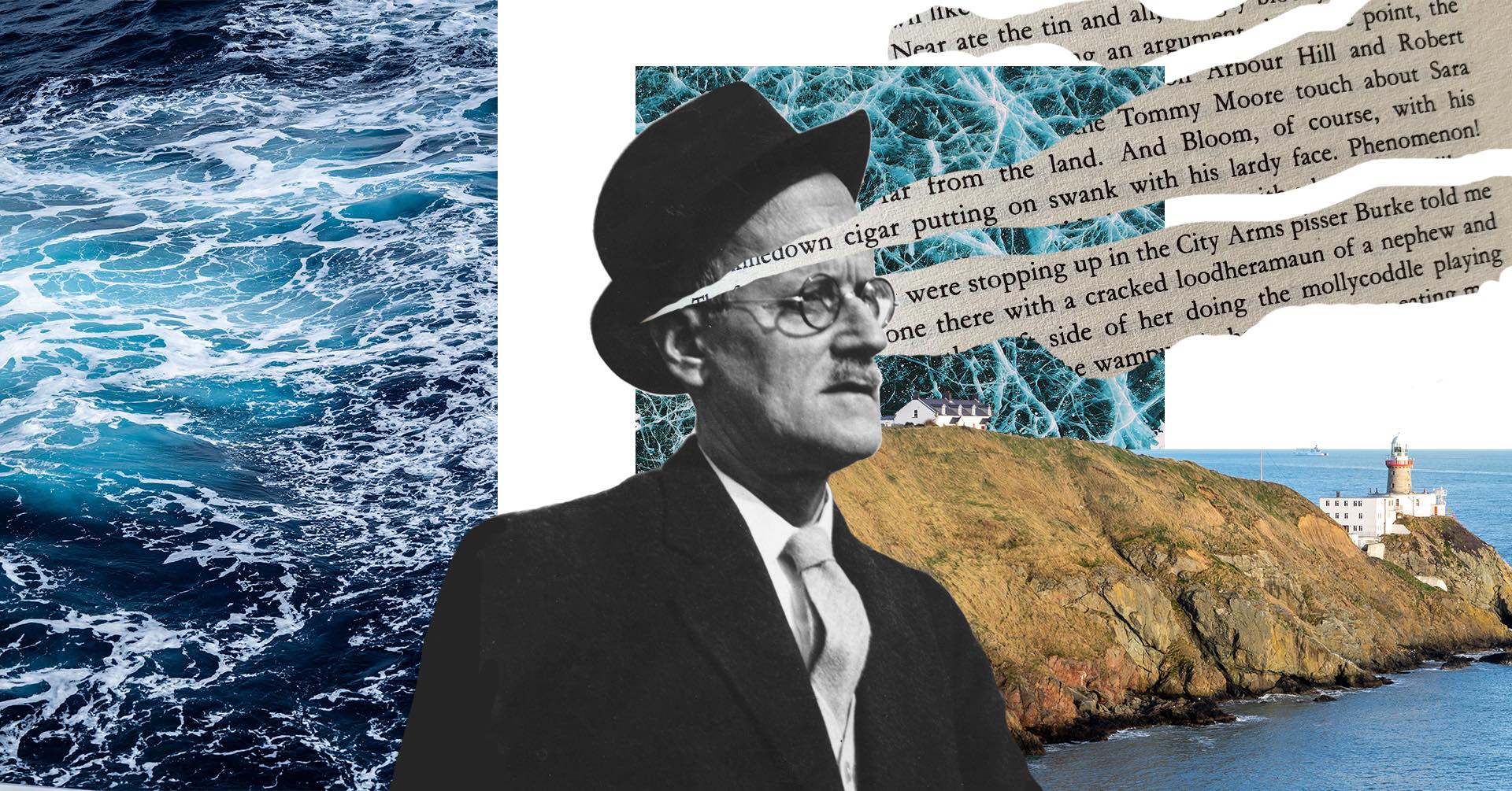

A century ago today, James Joyce’s daring masterpiece Ulysses was first published. It has since been acclaimed as a landmark in literary history, and (by some) as the greatest novel of the twentieth century. Yet its roots go much deeper. As its title suggests, the novel features a substantial link to the ancient world: Ulysses is a retelling of Homer’s Odyssey.

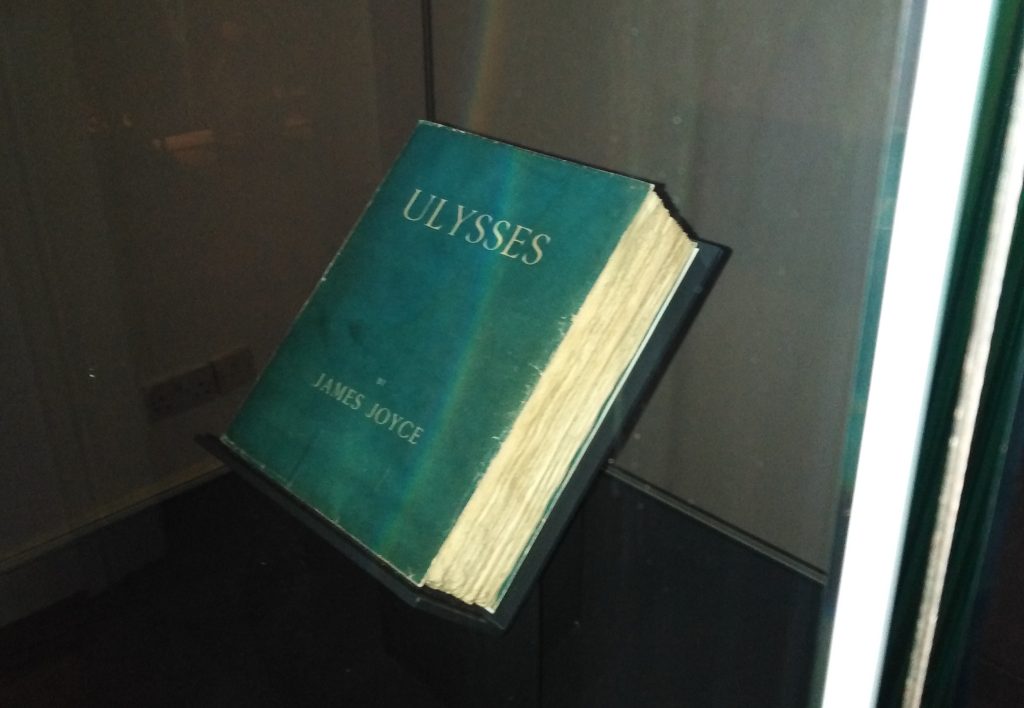

Instead of showcasing the adventures of Odysseus’ journeys over the ten years after the fall of Troy, however, it instead follows the wanderings of Leopold Bloom, a polite, married man of Jewish background, across a single day in Dublin (June 16th, 1904). His various experiences across this one day each correspond to events from the Odyssey, and so do the various people he encounters. The novel is then, naturally, saturated with references to antiquity. Even the sea-blue colour of the first edition’s cover was chosen to evoke both the seas Odysseus travels upon, as well as the contemporary Greek flag.

The three main characters of Ulysses (Leopold Bloom, Stephen Dedalus, and Molly Bloom) are each ‘versions’ of major figures from the Odyssey. Joyce wished to create an ‘everyman’ character in Leopold Bloom, and he believed that Odysseus was the perfect model of a ‘complete man’. As he related to his friend, the artist Frank Budgen, during the novel’s gestation:

‘Hamlet is a human being, but he is a son only. Ulysses is son to Laertes, but he is father to Telemachus, husband of Penelope, lover of Calypso, companion in arms of the Greek warriors around Troy and King of Ithaca. He was subjected to many trials, but with his wisdom and courage he came through them all.’

Joyce’s desire with Ulysses was to celebrate ordinary, everyday life. He achieved this by choosing a decent but unremarkable man as his protagonist, and linking his life with one of the most famous heroes of world literature. He has frustrations and disappointments, but also joys and small triumphs. In many ways he is unlike Odysseus: he is a pacifist, and he is much more honest than Odysseus. Yet, like Odysseus, he has a great curiosity, and learns a great deal from those he encounters across his travels.

A substantial alteration from the Odyssey, however, is Bloom’s relationship with his wife Molly, Joyce’s analogue for Penelope. Whereas Penelope is Odysseus’ faithful wife, awaiting his homecoming (or nostos), Molly Bloom is having an adulterous affair with a brazen local loudmouth, Hugh ‘Blazes’ Boylan. Yet Joyce is unjudgmental in his portrayal of Molly’s infidelity. Indeed, her husband is aware of, and even tacitly approves of the affair. The couple’s marriage was permanently altered by the death of their young son just a few days after his birth eleven years prior to the events of the novel. Unable to be intimate with one another since then, the couple sleep head to toe of each other. Despite the infidelity, there is a great deal of love and warmth between the couple. During the famous soliloquy of Molly Bloom, she recalls vividly and with great warmth moments in their relationship. Part of the reason Bloom is wandering around for so much of the day is to give his wife privacy for her affair. Yet as Leopold wanders the city, he is haunted by the memory of his lost son.

Thirdly, we have the character of Stephen Dedalus. He is essentially Joyce’s fictional self-portrait and shares an abundance of the writer’s biography. He is the protagonist of Joyce’s earlier novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (essential reading for anyone wanting to read Ulysses). Stephen is still in his early twenties, and much younger than the thirty-something Blooms. Of course, Stephen Dedalus’ own name is a classical reference itself. Daedalus was the master craftsman of Greek myth, who created wings so that he could escape the Cretan labyrinth of the minotaur. He is also, of course, the father of the perhaps more famous figure of Icarus. Portrait of the Artist focuses heavily (yet subtly) on the myth of Daedalus, and features many instances of imagery regarding flight and wings. It opens with an epigram from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and closes with a metaphorical ‘flight’ from Ireland to mainland Europe.

Yet when we find Stephen at the start of Ulysses, he is not in full flight. He has returned to Dublin after his expedition abroad at the end of A Portrait of the Artist has ended unsuccessfully. Furthermore, during the time between the two novels, the character has experienced a painful bereavement, for which he feels culpable. His artistic ambitions have stalled, and he is a young man very much at a loose end. Stephen’s biological father, Simon, is still alive, but he is a very different man to his son. He is unable to offer the guidance and direction that the young artist needs.

Beyond the main characters, the structure of Ulysses is also based upon that of the Odyssey. Much like how the Odyssey doesn’t feature Odysseus until Book V (with the earlier books focusing on Telemachus), Bloom doesn’t show up until the fourth chapter. The early chapters of Ulysses instead focus on Stephen. Within the framework of the Odyssey, Stephen is therefore cast as Telemachus, Odysseus’ son.

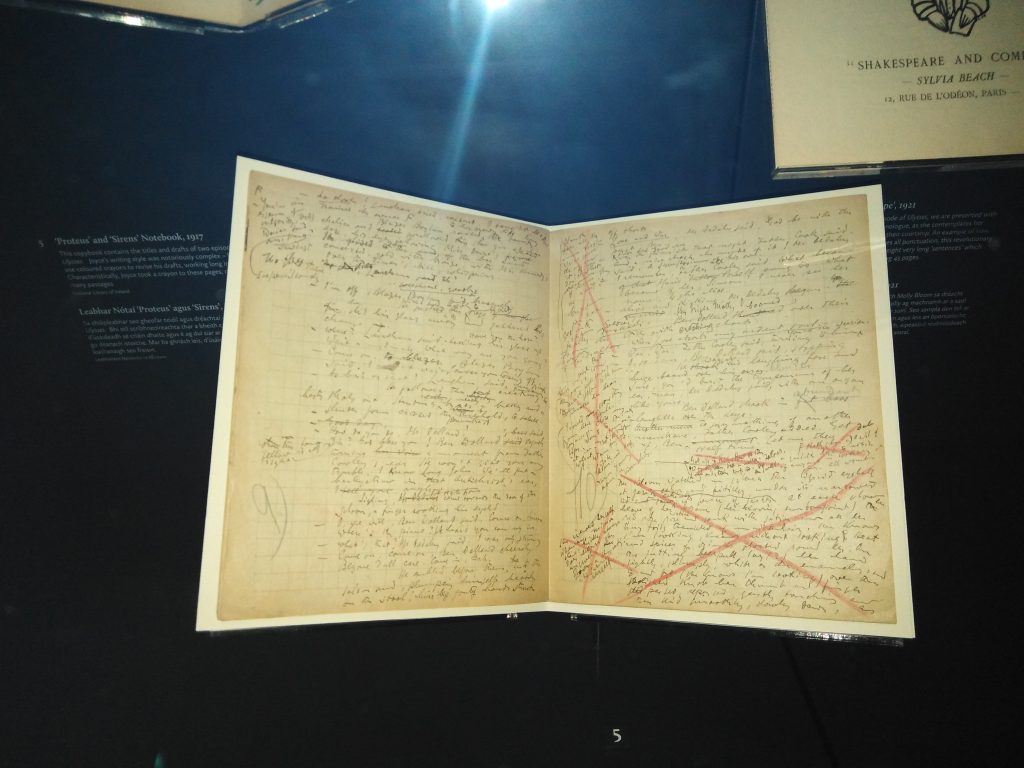

One of the stranger editorial choices across the writing of Ulysses was the decision to remove the chapter titles. These are present in Joyce’s notes for the novel, and have long been used in Joycean and academic circles, although they are absent from the novel itself. From the perspective of a Classics enthusiast, they are particularly illuminating: each chapter is named after a significant incident in the Odyssey. The classical allusions often work on a metaphorical level and the titles helps clarify these metaphors.

For instance, the central chapter of the novel features Bloom in a bar getting into an increasingly heated and antagonistic conversation with a bigoted antisemite, known simply as ‘the Citizen’. The notes reveal the title of the chapter is ‘Cyclops’, which recasts the entire situation. While the character has both his eyes and can see, his small mindedness has left him ‘one-eyed’. The chapter climaxes with Bloom fleeing from the bar as a biscuit tin is thrown at him, a humorous echo of the rocks Polyphemus hurled at the escaping Odysseus.

Beyond the events that take place, each chapter is written in a unique style that reflects the novel’s ancient predecessor in some way. The Aeolus chapter features multiple, continuous references to the wind, like that of the wind god Odysseus encountered. Similarly, the Sirens chapter has a significant emphasis on music, like that of the sirens’ song, with the novel even featuring sheet music.

The novel’s most experimental chapter is titled Circe and is set in Dublin’s Nighttown district (turn of the century Dublin’s red light district), where men metaphorically turn to pigs. Here, Stephen gets into an altercation with a British soldier and is left badly needing aid. Bloom is passing by and is able to come to his help. Bloom helps Stephen recover from the incident, and takes him to a bar wherein they encounter a drunk (Joyce’s stand in for Eumaeus, the swineherd). Bloom is able to leave Stephen in considerably better physical shape than he found him. More than that, however, Bloom’s act of kindness has inspired Stephen, and looks to elevate him from the rut in which he has found himself.

For all its experimentation and fearsome reputation, for all its allusions and footnotes, Ulysses is at core, about something very simple and very human. It is about a father looking for a son, and a son looking for a father.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.