Written by Alexandra Hudson, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

I recently visited the “Other Parthenon”—an exact replication of the Ancient Athenian Parthenon that was built in the early 1900s in Nashville, Tennessee. Like the original Parthenon, it was absolutely striking:

At Civic Renaissance, a publication I curate, we regularly reflect on the way in which the past informs our present. And this visit certainly offered lots of fodder for that. My visit caused me to reflect on how our commonly held contemporary views of education today compare to how people have thought of education in other times and places.

Today, it is far too common for people to view education as merely a means to an end. They think of it as a path to getting credentialed to the end of getting a job and earning a living. Too often, education today is associated primarily with acquiring knowledge or technical skills.

But it hasn’t always been this way.

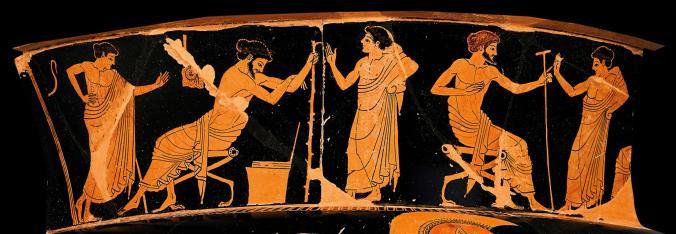

In past eras—including in ancient Greece and Rome—education wasn’t so static or utilitarian a concept. Education was understood as soul craft. It was character formation. It was exposure to a variety of different disciplines—geometry, rhetoric, philosophy, poetry, and more—knowledge meant to orient one toward the Good and the wellbeing of family, community, and the polis, or city.

Education’s end was to promote lifelong learning and curiosity. It was an attempt to cultivate our humanity to the fullest, so that we might bring our best selves to bear on the problems of our day.

The ancient Greeks’ word for this notion of education was Paideia. (In Greek, as many of you know, Paideia looks like this: παιδεία — do recognize π from middle school math? Greek is very phonetic!)

I’m currently reading Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture, by 20th century German classist Werner Jaeger. First published in 1933 in German, this book is a defining work of scholarship on the concept of Paideia. Jaeger defines it as education, but also culture. This is because Paideia refers to the process of shaping a Greek’s character. It was an all-encompassing approach to religion, politics, history, and literature, all to the end of defining and embodying what it meant to be a Greek citizen.

Greek Paideia found expression in ancient Roman culture in the term humanitas, a word that meant not just education and culture, but also benevolence and love of humanity.

Eric Adler recounts a relevant anecdote in his new book Battle of the Classics, recently published by Oxford University Press. When Cicero defended his teacher, Archias, in court, he urged the judges to show mercy “in order that he may seem to have been freed by your kindness (humanitas), rather than to have been violated by your cruelty (acerbitas).”

Humanitas—the quality of being humane, showing kindness and grace to our fellow man—was both an intellectual and a practical virtue. Cicero said humanitas was cultivated through studying literature and philosophy and other disciplines—the same curricula that Archias had taught Cicero.

Such a study softened the rougher edges of our human nature, teaching those who studied its ways to pursue peace and harmony with others and avoid cruelty and violence. It also made its students free—defined by self-discipline and control of the passions— and able to enjoy the fruits of life in a Republic.

It is no accident that the studia humanitatis or “the study of humanity” ultimately came to be referred to as the artes liberales or the “liberal arts.” The study of humanity, at its core, is appropriate for the education of those who wish to be truly free—as true freedom in the classical sense began in the mind.

For Seneca, philosophy was essential to any free person’s education, because only philosophy was believed able to transmit wisdom, virtue, and kindness—essential requisites to being truly free.

Harvard intellectual historian James Hankins reminds us that humanitas was an also important concept for the humanists of the European Renaissance of the 15th century. In his fantastic essay, The Forgotten Virtue, he looks to the example of humanists such as Erasmus of Rotterdam and Petrarch.

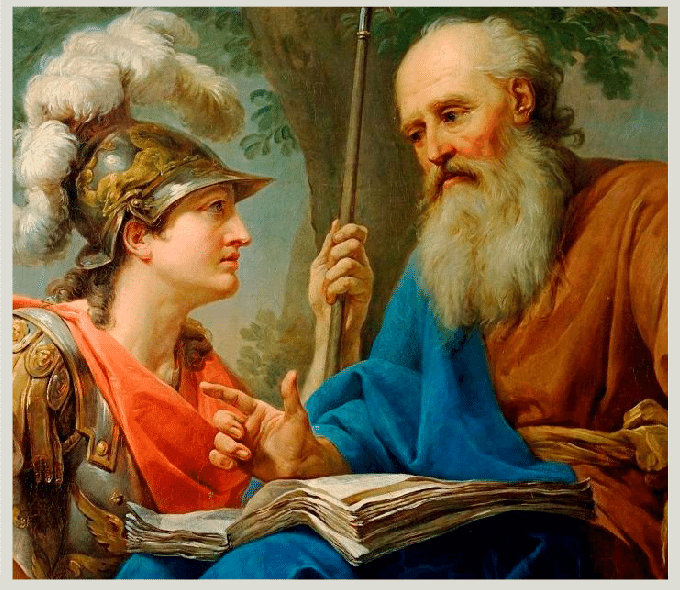

These thinkers thought that cultivating humanitas—what we might call civility today—was an essential part of education. Through the study of art, history, philosophy, and literature, the humanists instructed members of the ruling class in what conduct was praiseworthy, what was blameworthy, and what was worth emulating in their own lives and in their leadership. “The humanist theory of civility and humanitas linked civil conduct tightly with character,” Hankins writes.

Looking to how people in other times and places viewed education can help us think more clearly about our own time.

Our educational culture seems to have largely lost this vision of education. How can we revive an educational culture that cares about cultivating our humanity and benevolence to our fellow man?

How might we recover a vision of education that prioritizes a well-rounded education in the classics and the humanities, and sees education as something that cultivates our humanity and makes us truly free—one that doesn’t merely see people as units to be formed and fit into the job market?

Relatedly, how can we recover an educational culture that nourishes curiosity and promotes lifelong learning? These are good aims objectively, but as we discussed recently at Civic Renaissance, it might also go a long way to elevating our deep cultural and social divides today.

Paideia, humanitas and civility cultivate vulnerability and humility, virtues that are seem foreign in a moment that values comfort and certainty above all.

Epictetus said that the most important thing we can learn from Socrates is how to have a debate without it descending into a quarrel.

Why? Because Socrates was curious. He asked questions. He was a gadfly who pointed out hypocrisy—but he used humor and irony, not insult or brut force.

Socrates embodied the ethos of paideia, humanitas and civility when he reminds us in the Republic that our high aim in life should be to persuade those we disagree with—to turn our enemies into our friends, and to bring out the best in them. This is the sort of humanity we need today.

What do you think about paideia, humanitas, and civility? What role might they have today as we think of post-pandemic education? Please write to me. I’d love to hear from you! You can reach me directly at [email protected].

Alexandra Hudson is the Founder and Curator at Civic Renaissance, a newsletter and intellectual community for those who care about ideas and who are interested in using the wisdom of the past to help heal our divides, and revive grace and civility in our public discourse today.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.