By Kevin Blood

It was a widespread cult of enormous importance in the ancient world. Socrates’ last words referenced its central figure. Their symbol is still recognizable today, worldwide – even if you don’t know what it is, you’ve likely seen it. But what exactly was the cult of Asklepios?

Established towards the end of the sixth century B.C. in the ancient Greek city of Epidauros, the cult worshipped the ancient Greek god of healing and medicine, Asklepios. The Temple of Asklepios at Epidauros flourished as a healing centre thanks to the careful management of its priests, and the cult’s temples and sanctuaries spread and went on to provide health services for the people of the Graeco-Roman world.

According to myth, Asklepios was the son of the god Apollo, and a mortal woman, Koronis. Apollo loved Koronis, yet her father, King Phlegyas, arranged her marriage to a mortal man. Jealous, Apollo killed the groom with an arrow. In turn, the goddess Artemis killed the pregnant Koronis in the same manner. Apollo saved Asklepios from his mother’s womb, and he was then fostered and tutored by the centaur Kheiron, who taught him the healing arts of medicine.

Asklepios became such a skilled healer that he could raise the dead. At the request of Artemis, he restored her favourite, Hippolytus, to life. For his interference in matters of life and death, Zeus, the king of the gods, killed him with a thunderbolt crafted by the Cyclopes. Angered by this, Apollo killed the Cyclopes in revenge. After his death, Asklepios was worshipped as a god.

This mythical history was first set in Thessaly. The priests of Epidauros, however, localised it and established Asklepios’ connection with their city. From there, other cult centres dedicated to Asklepios spread. One was established in Athens in 420/19, with the support of the playwright Sophocles.

His sanctuary at Epidauros came to be the site of quadrennial games, the Asklepieia, similar to other Panhellenic festivals, such as the Olympics. To accommodate these games, the sanctuary at Epidauros grew to include an amphitheater, a stadium, a gymnasium, and dormitories. However, the primary reason the sanctuary gained acclaim was for the healing rituals carried out by the priests of Asklepios.

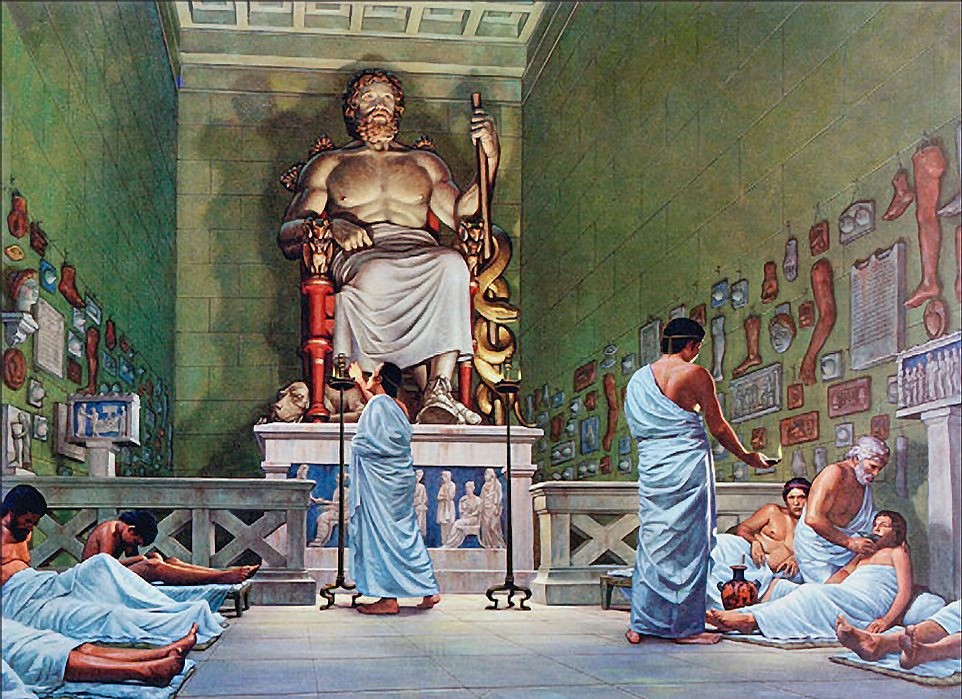

One such ritual carried out at Epidauros involved the sacred snakes of Asklepios. The snakes were a symbol of rejuvenescence (for the snake shedding its skin was believed to renew its youth) and blessed serpents were housed in the temples of the god; the snakes were thought to heal the sick by licking them. The symbol of the staff of Asklepios entwined with a snake is still today associated with medical organisations.

Those who wished to be healed would be purified in the holy waters that flowed from the sanctuary’s sacred fountains; they partook in cleansing rituals involving sacrifices and ablutions. Only those free from blemish, both moral and physical, could enter the holy shrine. To prevent pollution, pilgrims abstained from sexual intercourse, and it was forbidden to die or give birth within the sanctuary. Once in the temple proper, they were taken to the ‘incubation place’, which was forbidden to the impure. Divination also took place there. This involved the god’s visiting sleepers in dreams, whereupon he revealed the right remedies.

Alternatively, cure took the form of a consultation with the priests who would interpret advice given by the god. This melding of cures with smart propaganda saw the sanctuary at Epidauros remain popular right up to A.D. fourth century.The renown of the sanctuary helped it morph from an oracular shrine dedicated to the practise of incubation, to a sizable complex of baths.

Some scholars attribute the rise in popularity of the cult in democratic Athens as a response to the plague that devastated Athens (430-426 B.C.). It could be that these cult sanctuaries in Athens provided some with healing and respite from the ravages of the plague. We do know that Asklepion sites were chosen for their natural beauty, spacious with clean air and pure, flowing, waters.

Written sources suggest the regime of cleansing, bathing and other ritual purifications were legitimately beneficial. The taking of the open air was said to be restorative. That’s not to mention the powerful spiritual and religious benefits they believed they gained through ritual sacrifice and worship of a powerful health-giving deity.

The Hellenistic era saw shrines dedicated to Asklepios increase. The Askelpion of Kos gained a status comparable to the centre at Epidauros. The popularity of the cult spread to Rome and throughout the Roman empire, providing important health services.

The Hellenistic era saw shrines dedicated to Asklepios increase. The Askelpion of Kos gained a status comparable to the centre at Epidauros. The popularity of the cult spread to Rome and throughout the Roman empire, providing important health services.

Even today, milennia after the fall of the Roman empire, the symbol of Asklepios can be seen emblazoned across ambulances and hospitals. It’s good to know the legacy of the god is in good health.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.