Written by Mary Naples, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

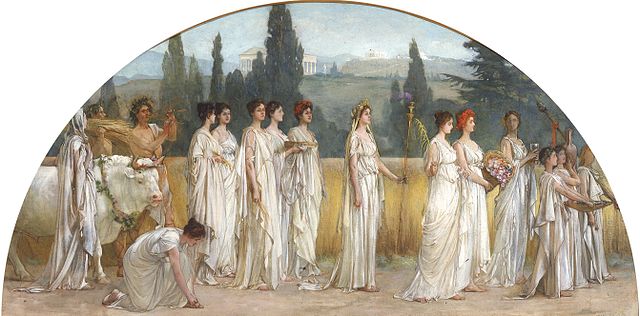

Clad in white robes and carrying torches, the dawn’s amber rays cast a golden glow on the hundreds of pious women as their procession passed through the polis. With their heads raised to the heavens, the sound of their fervent voices singing in praise of Demeter reverberated throughout the city walls. Faithfully, the people came out for them. From masons to magistrates, citizens and slaves alike packed the city streets standing elbow to elbow just to catch a glimpse of the spirited cortege as it made its way to Demeter’s sanctuary for the opening of their fertility festival–the Thesmophoria–the most highly anticipated religious festival of the year.

For as long as anyone could remember, throughout ancient Greece from the Archaic to the Hellenistic eras (800 BCE-31 BCE), citizen wives came from far and wide to gather in their cities to celebrate their annual feminine fertility festival honoring Demeter, goddess of the harvest and her daughter, Persephone, queen of the underworld. Primarily a fertility cult, in most cities the Thesmophoria ushered in the sowing season and was the largest of a series of fertility cults devoted to human as well as crop fertility.

In order to understand the Thesmophoria’s influence it is useful to examine what set it apart from other fertility festivals. The Thesmophoria was the most widespread and the oldest of all religious festivals in the Greek world, spanning from Sicily in the west to Anatolia in the east; from Macedonia in the north to North Africa in the south–in total possibly comprising as many as one-hundred cities throughout the Greek world. There is evidence that it was even celebrated during the Ptolemaic period (332 BCE-30 BCE) in ancient Egypt.

In fact, scholars believe that the Thesmophoria’s ubiquity in the region is testament to its prehistoric origins–predating not only the Iron age of ancient Greece but the Bronze age of Minoan Crete as well, possibly harking back to the the advent of agriculture itself with origins believed to be rooted in the Neolithic era.

At first glance it might seem counterintuitive that a women’s fertility festival would be given such a high priority in androcentric ancient Greece, after all women lived on the margins of society, removed from the public sphere. Could the strict demarcation of gender roles actually have served to empower women in ancient Greece?

Although typically confined to the seclusion of their domiciles, literary and archaeological sources suggest that, depending on their municipality, women in ancient Greece left their homes and families for anywhere from three to ten days in order to participate in the Thesmophoria– an occurrence of particular significance in and of itself.

For example, in some poleis such as Athens, Sparta, and Abdera the Thesmophoria was celebrated for three days, while in other cities like Pella it was celebrated for five days. At ten days, Syracuse (Sicily) celebrated it for the longest. While most poleis celebrated during sowing season in the autumn, in some poleis such as Delos and Thebes, the festival took place in the summer. Membership in the Thesmophoria was restricted to citizen wives in good standing, that is to say wives of male citizens, as women could not be citizens in ancient Greece.

The “good standing” refers to wives who were not adulterous. Unless he seduced another man’s wife, adultery for men incurred no penalties but such was not the case for the gentler sex. In Athens, if a woman was convicted of adultery, she could no longer share her husband’s oikos (house) and she was forbidden from women’s ritual events. Further, no maidens nor female slaves were allowed in the Thesmophoria.

Although responsible for the expenses related to its celebration, men were strictly prohibited from attending any portion of the event. In addition to their financial support for the Thesmophoria, men’s reverence for the cult was reflected by the cessation of certain civic functions on the second and most sacred day of the festival.

In Athens, the Boule Council—a body of five hundred who set the agenda for the democratic assembly– was unable to meet. Moreover, law courts were completely suspended and all prisoners were released from jail. Indubitably, there were other feminine festivals devoted to fertility, but none as respected as the Thesmophoria.

To appreciate the significance of a feminine only cult festival garnering esteem from the entire community–including male citizens–it is important to get a glimpse into what life was like for women in ancient Greece.

A woman’s place was in the home tending to such things as nursing children, weaving clothing and preparing food. Women were even restricted from the trivial task of marketing as it was believed that women could not manage financial transactions as complicated as purchasing fruits or vegetables. Needless to say, if a woman could not be entrusted with the simple job of making change, there was no question of giving them the vote in this newly democratized society.

Because male citizens could only be borne from citizen mothers/wives, the citizenship a wife shared with her husband was a watered down variety merely entitling her to bear his children–most importantly his sons. In her iconic book, Citizen Bacchae, Barbara Goff argues: “Women (citizen wives) had the ability to bear children who would be citizens, thus to transmit what they do not themselves possess.” (Goff. 164)

Therefore, a latent or passive sort of citizenship was the only kind doled out to the second sex. Besides passive citizenship, although women played a major role in the collective imagination of the polis, they were restricted from entering it. Even leisure activities were off-limits to them. While often represented in drama, female roles were played exclusively by males. Not only that, most scholars today believe that women were even banned from attending performances.

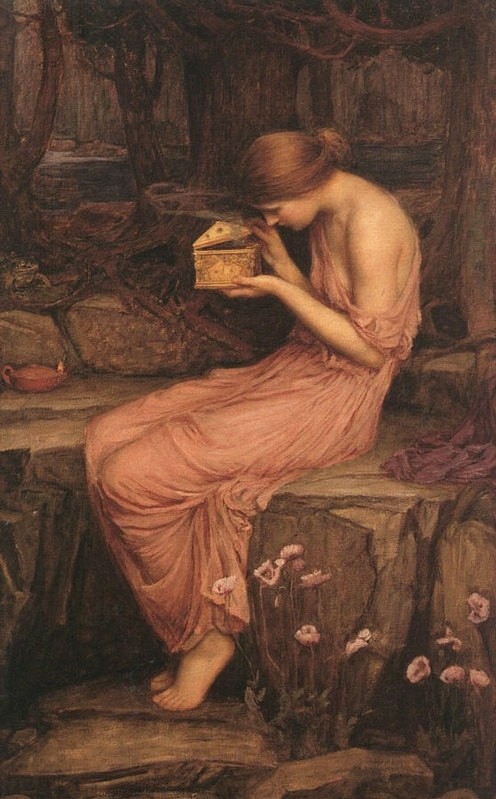

Dating back to Hesiod’s (8th century BCE) myth of Pandora it was imagined that women were her descendants and as such were a consequence of an unrelated act of creation. It is worth knowing that not unlike Eve and the forbidden apple, Pandora, was the first mortal woman whose action of opening a jar or pithos thrust humanity into a tailspin by releasing evil into the world.

Of Pandora, Hesiod writes: “She was sheer guile to be withstood by men.” then he adds “For from her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble, no helpmates in hateful poverty, but only in wealth.” Truth be told, men viewed women as separate entities and compelled them, like slaves or foreigners, to remain outside the community.

In fact, the opposition between male and female was a guiding principle for the Greek world. While males begrudgingly saw women as a necessary and vital element of life, women were also considered dangerous, disagreeable, and as an entity to be excluded at all costs. This disregard is evident from the mouths of three respected Athenian males.

In his famous funeral speech, renowned Athenian statesman Pericles (495 BCE-429 BCE) bellowed: “The greatest glory of a woman is to be least talked about by men whether they are praising or criticizing you.” And according to the sage Aristotle (384 BCE- 322 BCE): “The male is by nature superior and the female inferior…the one rules and the other is ruled.”

Lastly, setting us straight on women’s roles, an Athenian politician, Apollodorus of Archarnae (394 BCE-343 BCE), blathered: “Hetairai (courtesans) we maintain for pleasure, concubines for daily care of our bodies, but wives to give us legitimate children and to be loyal guardians of our households.” In consideration of the poor opinion men had of women, how did women’s alignment with the natural world serve their better interests?

Salient to this discussion is the place agriculture had within the polis. In his book about the Peloponnesian War titled A War Like No Other, Victor Davis Hanson asserts: “…agriculture was the linchpin of all social, economic and cultural life.” The seat of Western civilization, ancient Greece gave us their genius for philosophy, literature and politics, yet contrary to this cosmopolitan image it was chiefly an agrarian society, where most of its residents worked the land. From the seventh through the fourth century BCE, farming was a commonplace occupation revered by the greater polis.

In fact, farming was so integral to ancient Greece that even the word polis (city/state) has two components to it: the city proper or its urban core such as Athens and its corresponding agricultural hinterland, which for Athens was Attica. In his Socratic dialog titled Oeconomicus, the Greek historian and philosopher, Xenophon (431 BCE -355 BCE) pronounces: “When farming goes well, all other arts go well, but when the earth is forced to lie barren, the others almost cease to exist.”

Indeed, the community’s health was contingent on a successful harvest but because the land tended to be non-arable, success or failure was often determined by factors over which they had no control, often making their lives tumultuous. But as important as a good crop was to the health of the city/state, it was not their only fertility concern. Due to their ever-expanding empire, they needed an ample supply of males to maintain their military commitments and they needed women that is to say citizen-wives to produce the much-coveted male citizens.

Is it any wonder that the Greeks had such a preoccupation with controlling fecundity, celebrating several fertility festivals throughout the year? Representing the changing seasons, most of these cult festivals were associated with Demeter, goddess of the harvest, who represented abundance in all natural things.

Terracotta group of two seated women thought to be Demeter and her daughter Persephone. North-west Asia-Minor, circa 180 BCE, The British Museum, London

Their pious respect for a higher power associated with fertility allowed them a sense of control in their otherwise chaotic lives. With the exception of the Eleusinian Mysteries which included men and hence would become more renowned, membership in the fertility festivals was limited to women only.

Apropos of the Mysteries, In her opus, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, Jane Ellen Harrison proposes that the Eleusinian Mysteries issued forth from the more antiquated Thesmophoria.

Did women exploit their gender roles by accentuating their connection with the natural world? Women were the natural agents of fertility cults considered all-important in the agrarian culture of ancient Greece. Though excluded from the daily activities of life within the public square, cult activity allowed women agency with organizational processes and religious rites.

John J. Winkler, in his book The Constraints of Desire, proposes: “In a sense, the Demetrian feasts were official business of the polis, but carried out with a good deal of autonomy by women.”

Whereas the Thesmophoria was an autonomous enterprise, citizen wives were in charge of running this community, which held elections, drafted proposals, kept accounting and last but not least practiced sacred feminine ritual.

2 comments

The “Pandora’s box” painting is actually “Psyche Opening the Golden Box” by John William Waterhouse (1903). As correctly noted in the text, Pandora opened a jar, not a box.

Great article. When’s the last time anyone saw a fertility festival, honoring women (what men cannot do!), in the Western World? Sign of the times.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.