by Lydia Serrant, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

There is no doubt that the Romans drew a lot from the Greeks. This included their love of theatre.

Roman theatre took a while to take hold, but once it did, it was popularised across the Empire and evolved over the centuries. The Romans adopted many of the Greek gods, so the mythological plays of Attica were a natural choice for the Roman Theatre. However, the Romans had a bloodthirst that was unrivaled by the Greeks, and overall they preferred a violent comedy to the slower and more philosophical tragedies.

That was not to say that Roman theatre was void of popular tragedies. The earliest surviving tragedies by Ennius (239 – 169 BC) and Pacuvius (220 – 130BC) were widely circulated and therefore, preserved for later audiences.

It was the Greco-Roman poet and former slave Lucius Accius (284 – 205 BC) that popularised theatrical Tragedy and introduced Greek Tragedy for Roman audiences. The Romans liked the adaptations so much that they used Lucius’ translations of Homer’s Odyssey as an educational book for over 200 years.

Infrastructure

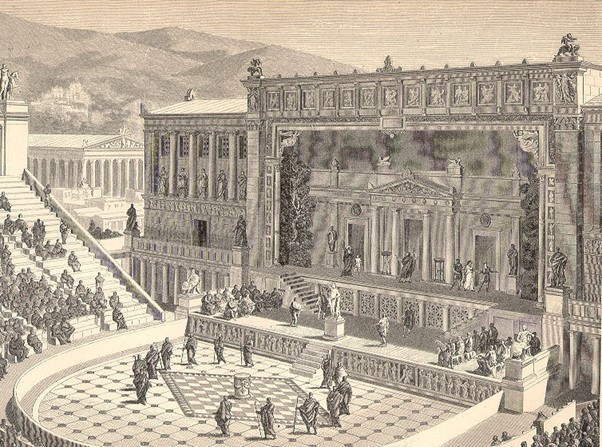

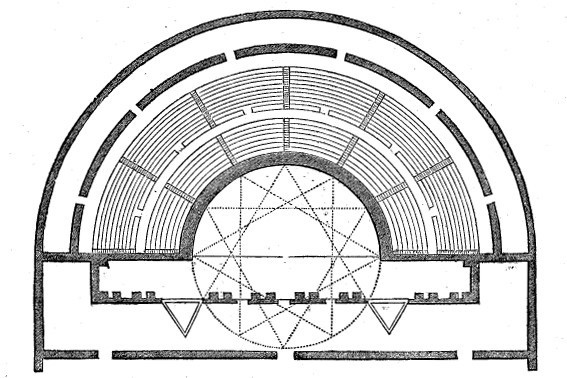

The physical structure of the theatres is the first tell-tale sign of how the Greek plays were adapted for a Roman audience.

Greek theatres were traditionally carved out of hillsides, whereas Roman theatres were built brick by brick from the ground up.

This was not because the Greeks were incapable of building magnificent theatres; history has left us with some astounding examples of ancient Greek architecture. The Greeks preferred hillsides because they did not use backdrops or props. Hillsides overlooked the city, and most of the Greek plays were set in Athens.

Of course, the Romans were not in Athens and therefore incorporated the use of backdrops and stage props to propel audiences back to ancient Greece. This also allowed to make the play more of a spectacle (in fact, the word spectacle derives, from the Latin Spectaclum meaning Public Show).

Roman Plays

The Romans copied much of the Greek when it came to storytelling and performance. There were some differences but the basic concepts remained the same, and many of the Greek plays were translated for Roman audiences.

When the Roman translation of Homer’s Odyssey first hit the Roman Theatre scene, it was quickly followed by Achilles, Ajax, the Trojan Horse, and later popular comedies such as Virgo and Gladiolus.

The Romans were not without original imagination when it came to playwriting, but most of the early plays were modelled after 5th-century Greek tragedies. Later comedies favor the newer style of comedy popularised under Alexander the Great that focused not on the epic tales of the gods but on the deeds of everyday citizens.

The Seneca Plays

Seneca was a known Stoic, and a great admirer and scholar of Greek philosophy. So how much Greek culture did Seneca consciously or unconsciously absorb into his plays?

Only eight of Seneca’s plays have survived to this day, Furens, Hercules, Medea, Phaedra, Troades, Oedipus, Thyestes, and Agamemnon. Hercules Oetaeus and Octavia are regularly accredited to Seneca, but are likely not his original work.

While it is probable that Seneca’s plays were performed within his lifetime, historians are not certain of this. What is certain is that the plays had a profound impact on theatrical history. Seneca exclusively wrote tragedies based on Greek myths.

The Romans got from Seneca’s plays what they could not get anywhere else, the opportunity to be both entertained and to learn from the philosophical master.

Seneca’s plays struck a chord with the masses and are still enacted to this day. They remained popular across medieval Europe and throughout the Classical renaissance.

His plays differ from the original Attica (Greek Athenian) plays in that they follow a five-act form instead of the traditional three, and they incorporated rhetoric structures that argued for a particular point of view or philosophical stance.

Seneca entrenched his plays in turmoil and personal conflict, and he focused on social and political issues that were relevant at the time and remain relevant to modern audiences. Known as fabulae crepidatae (Latin Tragedy with Greek subjects) Seneca’s characters were the mythological Greek characters of old, but each story was presented as a reflection of the audience’s mental state and condition of the soul.

Unlike the Attica plays, Seneca’s stage rarely gave way to the gods. Instead, inspired by the plays of Euripides and Sophocles, Seneca’s plays were bound with witches and spirits, and all manner of mystical and esoteric symbolism that resonated with this audience.

Seneca wrote his works primarily to be spoken, not enacted. However, later Roman taste preferred colorful plays to long-drawn-out auditory pieces, so actors were introduced along with costumes, props, and choruses.

As time passed and the Roman theatres grew larger and more grand, the spoken word became increasingly more difficult to hear, so the plays eventually incorporated the choir and orchestra to guide the audience’s feelings and emotions, rather than solely relying on Seneca’s rhetoric alone.

Seneca’s plays were written to affect the human psyche, and explore the moral and philosophical territory.

Like Shakespeare, Seneca did not write for a specific place or time, but through dialogues and soliloquies, his plays could be re-enacted at any point throughout history, which is a testament to their popularity and longevity.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.