By Van Bryan

Today we are traveling thousands of years into the past, to a time when the lives of gods and men became hopelessly intertwined, when ten-year wars were waged for honor, and when the heroes of the age fought tooth and nail to achieve their kleos aphthiton (eternal glory).

That’s right, today we are talking about heroes. More specifically, we are talking about Greek heroes or tragic heroes; some of you may already know that those two things are one in the same.

To understand the Greek hero and, more importantly, kleos, we must first understand the Greek song culture and the role that lyrical poetry, specifically Homeric poetry, played in the lives of classical men and women.

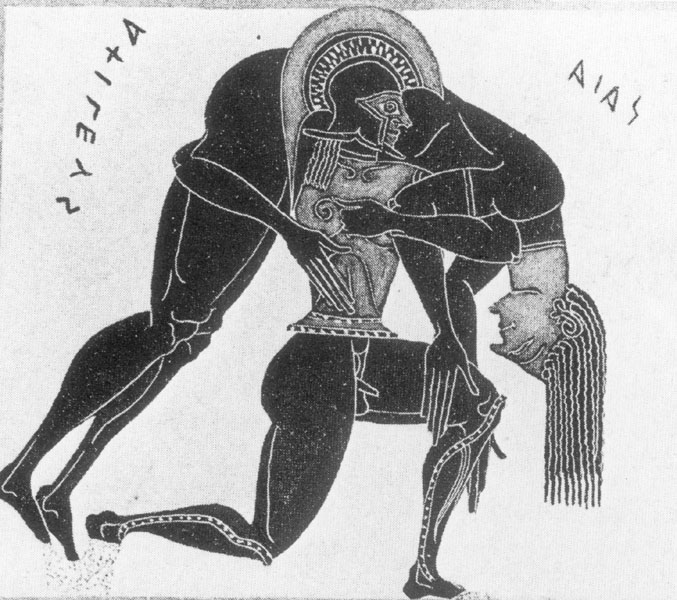

Hero worship in ancient Greece was a cultural staple, and lyrical poetry was the medium through which stories of heroic myths were passed down through generations. The ancient Greeks would have understood the tales of Achilles, hero of The Iliad, or Odysseus, the namesake of The Odyssey, in the same way that the stories of Jesus Christ are known by much of Western civilization.

Statue of Achilles in Hyde Park, London

Statue of Achilles in Hyde Park, LondonN.B. I’m not comparing Achilles and Odysseus to J.C. I’m merely stating that the overarching mythos of the Homeric characters would have been familiar to anybody from that age and culture in a way that the story of Jesus Christ is familiar to Western civilization and beyond.

Moving on…

So epic poetry was told, retold, and passed through the generations in the days of ancient Greece. It became something of a common thread within the ancient Hellenic society. For while Greece shared a common land mass, language, and religion, it was not one country.

The tradition of reciting the Homeric epics and retelling the tales of Achilles, Agamemnon and Odysseus would have been a shared cultural tradition through all of Greece-from Athens to Sparta, Crete to Corinth.

What Is Kleos?

Okay, okay. That sounds all well and good. The poor ancients didn’t have television or Xbox so they passed their time reciting Homeric verse. There are certainly worse ways spend an evening.

But let’s get to the question at hand. Remember, we were talking about the tragic hero and his, or her, pursuit of kleos. So, first things first. What is kleos?

The first thing we should recognize is that there is not an exact translation for kleos. It most closely translates to “glory” or, more specifically, “what people say about you”.

Triumph of Achilles, by Franz Matsch

Triumph of Achilles, by Franz MatschWhen it comes to heroic glory, kleos is actually the medium AND the message. Kleos was the glory that was achieved by Homeric heroes who died violent, dramatic deaths on the field of battle. However, kleos also referred to the poem or song that conveys this heroic glory.

The Iliad, therefore, is a type of kleos. It is the song of Achilles, the main hero of the epic who achieved eternal glory on the battlefields of Troy. Another name for the city of Troy was Ilium. This is where we get the name “Iliad”.

However, kleos is not just something that is handed to you. You have to pursue it, often at great personal sacrifice. Achilles is quoted as saying…

“My mother Thetis tells me that there are two ways in which I may meet my end. If I stay here and fight, I will not return alive but my name will live for ever (kleos): whereas if I go home my name will die, but it will be long ere death shall take me.” –Achilles (The Iliad)

Here we get to a major crux of the Homeric epic. It is that all-important question for classical heroes. Do they die young and gloriously, and have their names live on forever? Or do they live long, humble lives, but die as anonymous old men?

To answer this question, let’s take a look at another Homeric hero, one that I’m certain you have never heard of.

In book XI, Homer takes something of a detour to tell us about the little known hero, Iphidamas. Here is a man who is an ally to King Priam and the Trojans; he was one of the first warriors to take up arms against the Acheans (the Greeks) when they set sail for Troy. He is also the first warrior to face King Agamemnon in battle.

“Tell me now ye Muses that dwell in the mansions of Olympus, who, whether

of the Trojans or of their allies, was first to face Agamemnon? It

was Iphidamas son of Antenor…”- Homer (The Iliad, Book XI)

Iphidamas’ part within The Iliad is short-lived. Agamemnon kills him and strips his armor from his body.

“…he (Agamemnon) then drew his sword, and killed Iphidamas by striking him on the neck. So there the poor fellow lay and slept the sleep of bronze, killed

in the defence of his fellow-citizens, far from his wedded wife.” –Homer (The Iliad, Book XI)

So, what’s the big deal? Iphidamas is just one more dead soldier in a great war? Why do I bother to bring him up?

The part you don’t know is that Iphidamas had been wed to a beautiful woman around the same time that the Acheans set sail for Troy. Given the choice to stay and live in newlywed bliss or go and fight the Greeks, Iphidamas does not hesitate to abandon his newlywed wife to fight and die in battle.

Why does he do it?

You guessed it, for kleos.

Achilles makes a similar choice. Prompted by the death of his comrade, and lover, Patroclus, Achilles sets off in a fit of rage to slay Patroclus’ killer, prince Hector of Troy.

He does this knowing full well that with the death of Hector will signal the coming of his own untimely demise. He presses on nonetheless. Achilles will not be denied his glory.

Why Do Heroes Need Kleos?

Some of you might be wondering what exactly is wrong with these ancient warriors. Achilles storms off towards his certain death when he could just as easily live a long life back home. Iphidamas leaves his loving wife, opting instead to die on the battlefield.

They did it for kleos, for glory. But why? Why was glory so important that these men would forfeit their lives to achieve it?

Now that really is the question.

The answer has to do with the immortalizing power of kleos. Achilles chooses his eternal glory, which would live through the centuries in Homeric verse, over his natural life, which is destined to end in death.

From the perspective of our modern culture, we might assume that stories of heroism are not as “real” as our own lives. The idea that we might live on forever in the hearts and minds of our countrymen does not have as much credence today as it did in the Homeric world.

After all, it was the great philosopher, Woody Allen, who said…

“I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work; I want to achieve immortality through not dying. I don’t want to live on in the hearts of my countrymen; I want to live on in my apartment.”

However, we must remember that ancient Greece was a song culture. The Homeric epics were not merely fiction. They were considered to be real. More importantly, they were thought to convey the ultimate truth-values of the ancient Greek culture.

To a Homeric hero, a glorious death was more important than a long life.

Achilles would have viewed his kleos, his eternal place in history, as being just as “real”, perhaps more so, than his actual life.

Also, the ancient heroes, more than anything else, strived to be god-like. The defining trait of gods is their immortality. Achilles, although he was born to immortal Thetis, a water nymph, is a mortal.

By achieving kleos, the hero, in a sense, achieves immortality. He is godlike, eternally glorious. His name will forever be remembered and recorded in the catalogues of human history. So now we come to understand the paradoxical idea that, in order to live forever, a hero must first die gloriously.

2 comments

This is an excellent article and thanks for posting it. Here’s one small corrective quibble: in the first sentence of the fourth paragraph, the text mistakenly reads “lyrical poetry” when it should read “epic poetry.” Here’s a question for everybody who visits this site: if I’m a U.S. Army career soldier who volunteered for multiple tours of duty in Iraq, if I had to make deals and call in favors that were owed to me in order to be sent to Iraq additional times, does that qualify me as a seeker of kleos?

@ Stephen W. Richey

Yes it does.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.