By Ben Potter

The sun rises high over Rome’s Amphitheatrum Flavium, the mightiest arena in the world. Only the colossal statue of Nero, which one-day will lend the stadium its eternal pseudonym, dwarfs it.

The 50,000 strong crowd of men and women, young and old, rich and poor, are tightly coiled; one giant organism ready to strike, to unleash their wrath or their joy.

Though they are not the only ones with the glint of attack in their eyes.

A flash of light leads to a clash of steel, a spray of sweat, a cloud of dust, and finally, brutally, a cascade of blood which unleashes a frenzied pandemonium in the stands…

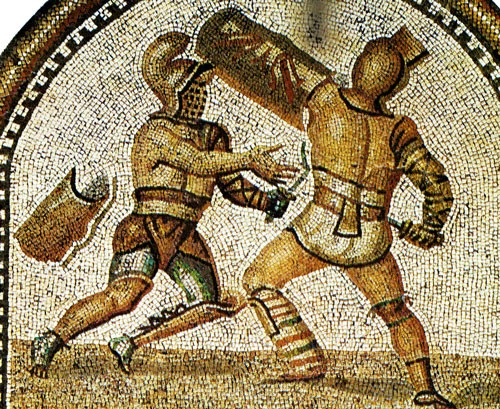

Those cognisant of TV shows like Spartacus, films like Gladiator, or indeed, any example from the swords and sandals genre, will be familiar with images of perfectly formed behemoths attempting to heroically empty their comrades of their entrails.

Though, as we shall investigate, Hollywood has not quite given us the full picture. I know, I know… shocking isn’t it!?

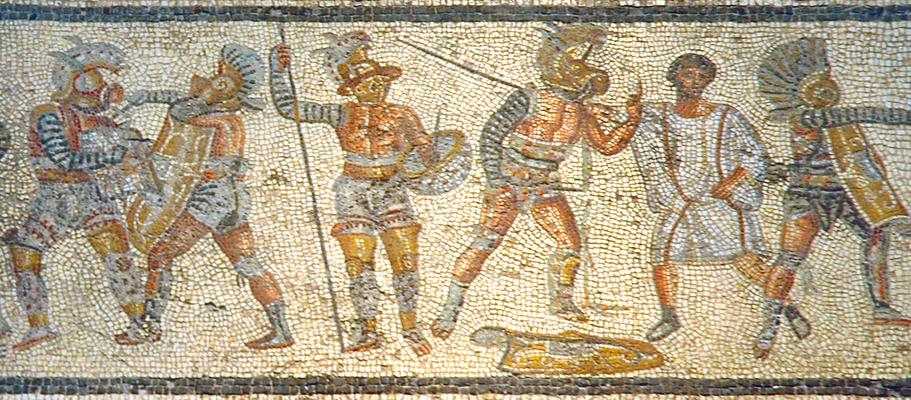

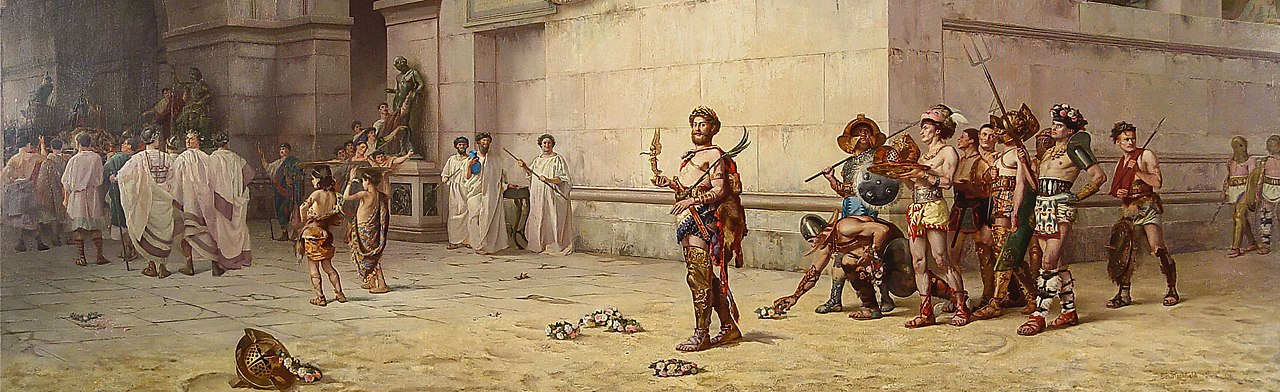

To begin with, gladiators were not perfectly formed. Indeed, they would be considered overweight next to modern sportsmen. Additionally, bloodlust was a secondary consideration to poise and finesse, and in fact, most gladiatorial bouts saw the loser escape with his life. Finally, and, crucially, large parts of Roman society considered gladiators to be anything but heroic.

As for the famous quote in the title (“Those who are about to die salute you”), it did genuinely occur in the pages of Suetonius.

However, it was supposedly uttered by a group of condemned men in an attempt to curry favour with the emperor, and not, as Tinseltown would have us believe, by every gladiator who entered the arena.

Indeed, it is highly unlikely that any professional fighter ever said it.

But before we conduct our gladiatorial post-mortem in earnest, perhaps a look at the origins of the sport is in order. (Unpleasant as it seems, it’s hard to deny that it was a sport – complete with match day programmes and scalpers selling tickets!)

As for the beginnings of gladiatorial combat, there is some dispute, though most agree it came out of the Italian peninsula… either from the Etruscans or Campanians.

What seems clear is that the games (ludi) were not intended to be the great public spectacle they later became. Instead, they were munera, a type of honorific spectacular dedicated to the spirit of a deceased ancestor.

What is really astonishing is how fast the event caught on. The first recorded munus was held in 264 BC, and within 200 years, their popularity and importance had become such that the Senate had to limit the size of the proposed munus of none other than Gaius Julius Caesar.

[N.B. Though if we compare how cinema has changed in only 150 years it is perhaps not so astounding.]

Even though the transition from munera to ludi was a gradual one, we can say with some confidence that by the time of Caesar, gladiatorial combat had mostly lost its connotations of filial duty. Instead, it had become a means of self-promotion and popular entertainment… and not just in Rome, but also throughout the rapidly swelling empire.

So what about the fundamentals of the games and, more importantly, the gladiators themselves?

A gladiator (from gladius, short sword) was the king of the sand, a mighty warrior, fiercely trained for one purpose only. He was a man of pride, dignity and above all else, discipline. He knew his life was forfeit and his only desire was to live and die with the stoicism and honour befitting his station.

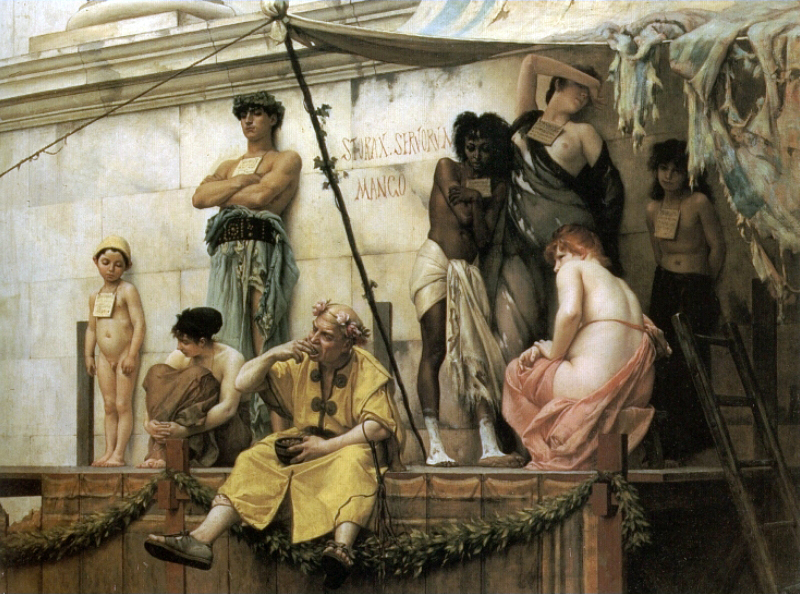

Despite the fact that gladiators were the celebrities and sex symbols of their day, they were also so deeply despised that the very word ‘gladiator’ was used as an everyday insult. They had no citizenship rights, were buried only with their own kind, and could have their lives expunged at the whim of their lanista (owner/overseer).

Essentially, they were a de facto category of slaves.

The antipathy felt towards these subhuman supermen is partly because of the social make up of the gladiatorial class.

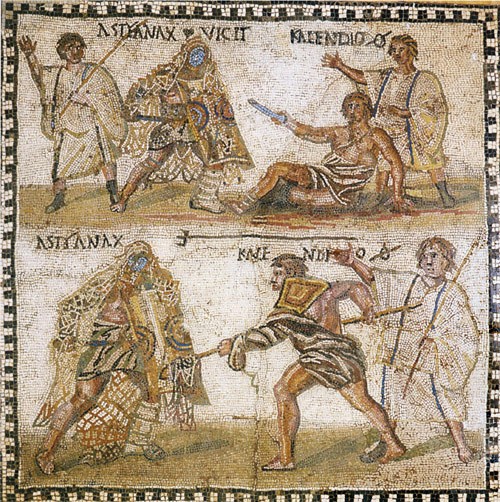

They were slaves of various origins: prisoners of war, citizens who had lost their rights or who couldn’t pay their debts, and various criminals from around the empire. Only if they were lucky, would they find their way into a ludus (gladiator school).

N.B. if they were unlucky they would merely be damnati (condemned to fight in the arena) or noxii (condemned to die a humiliating death in the arena). The difference being that the noxii would probably not be given weapons and their remains would be treated in a manner that would dishonour them for eternity.

All arenarii (people of the arena) were infames i.e. without rights or social status – a standing shared by prostitutes, pimps, actors and dancers. Gladiators, however, were both simultaneously far more lauded and reviled than any of these other controversial professions!

This was all very well for the impoverished, the enslaved and the criminal – indeed, many were happy to enter a ludus. It would mean good food (gladiators followed a high-calorie vegetarian diet), a roof over their head, and a potential to win money, freedom and that most intangible and strangely elusive of all things, fame!

Also, it got them out in the fresh air… which is nice.

The peculiarity, therefore, is not that many of the most desperate ended up in the arena, it’s that some of the more privileged actually volunteered for this ignoble and bloody fate.

Some scholars estimate that as many as half of all gladiators were volunteers (auctorati) by the time the games were at their height (1st century BC – 1st century AD).

But what really boggles the mind is that the lure of the games was so great that they even managed to entice aristocrats!

Indeed, it seems there was a significant minority of the noblesse who disgraced their family name, gave up promising political careers and disinherited themselves from great wealth. In fact, it was beholden upon Augustus, the moral champion of the 1st century AD, to make it illegal for the senatorial and equestrian classes to fight.

Despite the emperor’s absolute power, the prohibition seems to have had only limited success.

In addition, several emperors themselves are known to have stepped onto the sand. This created a bizarre paradox of a man at the top of the social ladder publically engaging in the most degraded and base activity possible within his own society.

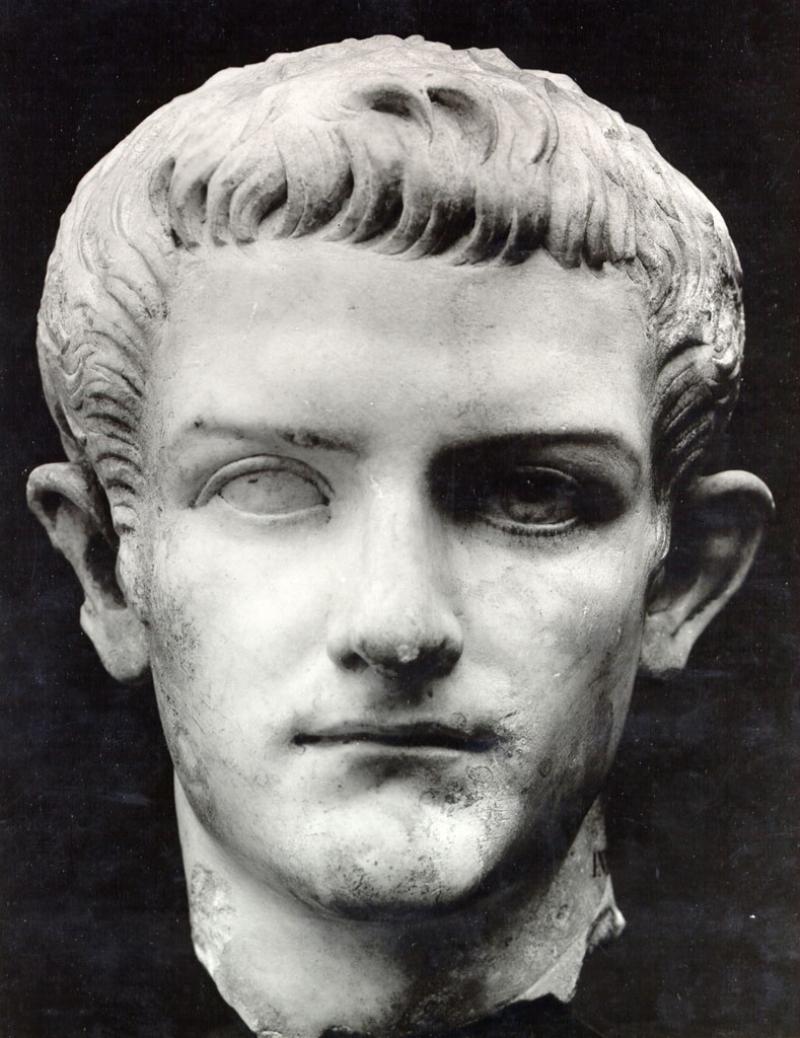

Caligula, Titus, Hadrian, Lucius Verus, Caracalla, Geta and Didius Julianus were all said to have crossed that stark line of dignity during their respective reigns. This was particularly amazing for Didius Julianus, as he was only emperor for nine weeks!

It is almost certain that none of the above competed with any seriousness and were merely making a populist parade of themselves or indulging a boyhood fantasy. (Though it’s hard to blame them; if I had unlimited power I would certainly insist on playing ten minutes of professional football).

However, the most enthusiastic, and therefore most shameful, participant in ludi was Commodus, the emperor who you may remember from that film with Joaquin Phoenix and Russell Crowe… the name of which escapes me.

Commodus was capricious, cruel and conceited (even by the standards of emperors). He was said to have killed 100 lions in a day and must, therefore, have had some physical and technical proficiency to avoid looking wholly ridiculous in front of the crowd; especially as he styled himself as the reincarnation of Hercules!

Indeed, the masses would have let him know if he had been entirely ludicrous. The games were one of the few conduits for egalitarian outpouring.

It was commonplace for the public to heckle, not just the participants of the ludi, but the on-watching ruling classes. In fact, it seems the games presented the ideal (perhaps unique) opportunity to present a petition to a politician in front of witnesses.

Though the games were unquestionably popular, (relatively) cheap to stage and helped school both combatants and spectators alike in the arts of war, they eventually fell foul in the later empire as a result of Christianity.

As early as the third century AD, the Christian scholar Tertullian denounced the games as murder, as pagan and as human sacrifice.

Perhaps it is no surprise that the first emperor to prohibit the spectacle was Constantine in the 320’s AD.

Though this was with little success; it was necessary to again curtail or prohibit the games in 384, 393, 399, 404, and 438 AD. By this latter date the Western Empire was dissolving into various warring factions and tastes in the Eastern Empire seemed more focused on theatre and chariot racing.

One of the hardest things for a classical historian to understand is the mentality of both the spectators and participants of a gladiatorial combat.

Though it obviously plays up to our baser instincts and, like so much sport, creates a tribal mentality, it goes so far beyond the most violent spectacles available to us today.

Regardless, there could have been nothing quite so dramatic, nothing that sent the heart aflutter and the limbs aquiver as the moment when a stricken gladiator raised a finger in submission, presented his neck to an opponent and all eyes turned to the editor (producer/sponsor) in whose hands the brilliant wretch’s life lay.

More than anything else, contemplating the bravery, daring and discipline of these ancient athletes only serves to highlight the egos, eccentricities and anti-social behaviour of their modern counterparts.

Despite doping, deflated pigskins, greasy palms and feigned injury, the worship, adulation and monetary rewards we bestow upon our physical elite shows no signs of abating.

Perhaps the Roman way is better, perhaps it’s a healthier approach: to marvel, to cheer, to applaud and goggle, but still, when the dust has settled and the blood has dried to remember that they are only mortal.

And much, much worse than that, that they are…yuck…entertainers!

2 comments

An astoundingly ignorant euphemization of the brutality of events in the Roman arenas.

The arenas’ sands drank the blood of children torn to pieces by wild animals, of women and girls raped by trained animals. Literally thousands could die during a major series of games.

Suggested reading: Mannix’s’ “Those about to die.”

That this site publishes such fantasies raises questions as to its editorial integrity.

Actually, I think this article is both entertaining and well-written, certainly not deserving of scorn. I would suggest, however, that the Roman games did evolve over time. As the political and social need for order and control increased along with the arrogance and depravity of Rome’s leaders, the games graduated in their brutality. For example, when the games first began, they were private affairs limited to a couple of slaves fighting to the death to honor a deceased ancestor, and death was not always the ultimate outcome of these “games.” Over time, however, the promoters of the games ( who, by then, recognized how lucrative and politically controlling the games could be) introduced the “damnatio ad bestias” (condemnation by beasts) into the arena. These condemnations were often presented as the ancient version of a half-time show and were designed to keep bored Romans glued to their seats. The mob watched as starved wild animals, trained (more accurately, tortured) by men known as “bestiarii,” were then set loose upon unarmed criminals, societal outcasts, and anyone who allegedly harbored “un-Roman-like” views (including women and children). By any definition, these displays were both bloody and cruel. “Damnatio ad bestias” would not become the preferred method of execution, however, until Caligula’s time. His unhinged character brought the games to a new height in bloodlust.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.