By Stella Samaras, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Orientalizing – Corinth (c. 720-535 BCE)

When the Dorians settled in the Attic Peninsula and the Peloponnese, many of the natives moved into the Aegean and across to Asia Minor. When they returned they brought back Eastern influences. Geometric pottery which incorporated simple human figures now began incorporating animals and mythical creatures in less symbolic and more realistic presentations e.g., chimeras and sphinxes.

This style was nurtured in Corinth from about 700 BCE, with the peculiarity that the Corinthians didn’t incorporate any human figures. Corinth with its established colonies in Corfu and Sicily and being a major trade centre, situated on the isthmus connecting the Aegean with the Adriatic Seas, was integral in spreading this style.

Animals and mythical creatures were painted onto a neutral base in dark slip clay which became black when fired; outlines were incised into the glaze, copying the technique of chasing a design into metal; and red and white were added to the drafting. The style showcased realistic rendering that harked back to Mycenaean vase painting, but was easier to apply to smaller vessels that are particular to Corinth i.e., the aryballos (a vessel for perfume).

A pouring jug, Oinochoe, Corinthian “animal frieze” style, ca. 580 BC.

Proto-Attic (c. 700-600 BCE)

Then the Athenians added the human figure to the orientalizing influence. This, along with a mish-mash of Corinthian influence and the emerging Black-figured Pottery and the Proto-Attic style came into being. The drawings became bigger; Corinthian monsters were added as were black figures in the Corinthian style, all while the geometric patterning was retained. There was a preference for bigger vases, large kraters and amphoras, as the Athenians experimented. Figures remained two dimensional and painted in profile.

As vase painting evolved it came to reflect the central place of the Trojan War and cycles of myths around Herakles (

Hercules),

Oedipus, Theseus etc., in the psyche of the Ancient Greeks. The stories were so beloved, they needed only the names of the figures to be understood. Often there are no identifying names, sometimes the names of the figures are written backwards and other times nonsensical strings of Greek characters are strung together to imitate names – it seems not all painters in Ancient Greece were literate.

Loutrophore. – A water carrier, Old Protoattic, (690 BCE). Athens, terracotta painted in black, attributed to the Painter of Analatos

Athenian Black Figure (c.600-500BCE)

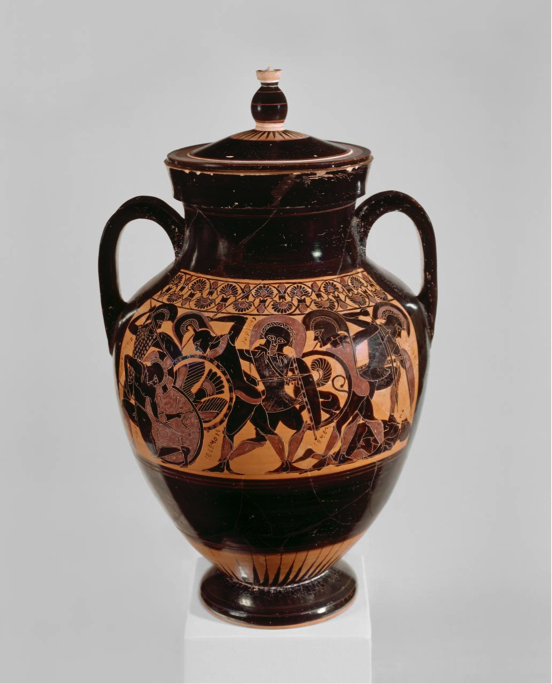

By the mid-6th Century, Athens overtook Corinth in the production of black figured pottery and began to innovate shapes of vases and refine their illustration. Shallow depth was added with the overlapping of figures and there arose an emphasis on greater detail. In this style clothing came to be depicted with a purple red pigment and women with white skin.

It is also a period for which individual potter/painter workshops are better understood and particular artists are remembered for their skill. For instance, Lydus is known for his details and rendering of animals, Amasis for his drapery, weapons and Dionysian themes. Exekias was renowned for his innovations including painting imitation eyes on the shallow outside of Kylix goblets so when they were raised to drink they stood in place of the drinker’s eyes.

6th C BCE Hydria Black figure from Athens

A black figure kylix which would have been drunk from at a Symposium. The eyes are painted over the design next to the handles c. 530BCE

Red and white pigments were added to the rendering of the figures that are drawn in black against the terracotta clay background. The black slip and the contrasting earthy red of the vase were deepened in hue by a process that involved firing the vase three times. The Athenians would become proficient at achieving tonal variations by glazing and firing their work in a strict process which they used in the concurrent style emerging, the red figure style.

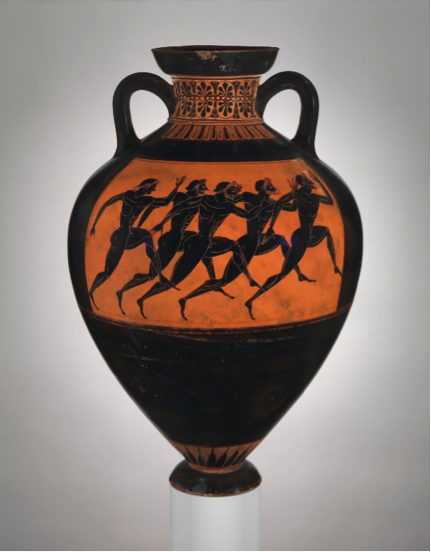

The illustrations continued to be grounded on a base line but could now be read from left to right in a narrative. Scenes from everyday life begin to creep in with the black figure style. The Panathenian Amphora (produced from 530 – c 300BCE) were commissioned for the Panathenean Games and given as prizes. On one side

appeared the Goddess Athena, on the other the sport for which it was awarded.

Psykter Amphora depicting scenes from the Trojan War in a variety of earthy tones, c.540BCE

One side of a terracotta Panathenaic prize Amphora c.530BCE, created by the Euphiletos

Athenian Red Figure (c 500-300 BCE)

By far the most popular of the styles today, the red figures take their colour from the iron rich clay of Athens. The warmth of the clay against the black background is iconic. Vase painters became highly specialised and would paint specific vase types. Drawing of figures finally broke away from two dimensional profile views with the occasional frontal view, to incorporating more natural three quarter views and naturalistic poses. Pliny attributes this to Cimon of Kleonai.

The incised lines of the black figure style gave way to raised painted outlines that could highlight specific details, such as muscles, and achieve the twisted “contraposto” stances the Greeks loved. Terracotta tones were added by adjusting the thickness of the glaze and also their firing technique, by Zeuxis. White, red and black were also used. Innovations in rendering were also achieved with painters employing foreshortening, twisted poses and aiming for greater naturalism.

Euphronios krater depicting Hypnos (left) and Thanatos (right) carrying dead Sarpedon, with Hermes in the middle. Attic red-figured calyx-krater, 515 BC.

Finally, with thanks to mural painter Polygnotos of Thasos, the baseline and adherence to painting in rectangular zones gave way to the placement of figures seemingly in the air as well as the base line. Always innovating, painters seem to be attempting to create a field of depth perspective by the new placement of figures. The clear run of a narrative was sacrificed for a resulting crowded in look.

This overlapped the black figure style and there are vases that employ both techniques. These vases are referred to as being bilingual.

During this period new vase shapes were added e.g, the lagynos, and existing shapes were adjusted. The kylix drinking cup became shallower while the water carrying hydria, became rounder.

Innovation was stymied with the war with Sparta (431-404 BCE).

Athenian White Ground

Hypnos and Thanatos carrying the body of Sarpedon from the battlefield of Troy. Detail from an Attic white-ground lekythos, ca. 440 BC.

Late in the 5th Century the white ground lekythos became popular as a funerary urn in Athens. A white clay slip was applied over the terracotta clay, on which a scenes, such as a central tomb being approached by women carrying garlands of flowers, were painted. Various colours were added in the decorations as a wash. It’s thought to be an imitation of a mural painting technique that hasn’t survived.

Ceramic Head Vases and Plastic Figure Vase

Finally, the ancient Greek novelty mug! It was shaped like a human head and was most likely used in Dionysian rituals and at Symposiums. In fact, there were aryballoi (perfume bottles), Kantharoi (mugs with vertical handles) and oinochoe (pouring jugs) shaped as heads.

Kantharos mug of a Satyr with vase painting c.460BCE, the Carlsruhe Painter

Sometimes referred to as being plastic, they weren’t plastic but sculptural in their formation. They first appear as Corinthian aryballoi in the 6th Century BCE, when they were shaped like deer, hares, women or helmeted warriors.

These creations were traded far and wide and it has been disputed whether they began in Greece. In Athens they never depicted Athenian males. Instead, they illustrated mostly women, but also satyrs, Dionysus, Herakles as well as Ethiopian males and females. They could have one head or two heads connected at the back in a Janis form.

Janis-form Aryballos vase 520-510 BCE

So, did the Ancient Greeks read comic books?

Hmm…if the storytelling on the black and red figure vases can be thought of as comic books, then dressing up (or right down) for the Elysian Mysteries or Dionysian Rites could be likened to attending Comicon. Bringing home kitschy mugs sculpted with a face or two of their favorite hero suggests that the Ancients Greeks were definitely comic book fans. Had they invented time travel, I know where I’d be searching for them today.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.