Written by Steven Whitehead, Contributing Writer of Classical Wisdom and host of the Spartan History Podcast

To the southwest of Thessaloniki, in northern Greece, lies the small town of Pydna. It was here on June the 28th, 168 BCE, that an already-crumbling Hellenic civilization began its final decline.

Under the leadership of Consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus, a Roman army crushed the Macedonian forces led by King Perseus – last in a royal line stretching back to Alexander the Great. In so doing, the Romans proved both the ascendency of their manipular tactics over the phalanx, and the Latins over the Greeks.

From a relative zenith in the years following the Greco-Persian wars, the various independent city-states of Greece began to devour themselves in a series of internecine wars, with the Peloponnesian conflict between Athens and Sparta as a stand out. Bled dry as a result, the squabbling Hellenes could offer little resistance when the rising power of Macedon swept south, first under Phillip and then his son, enforcing submission to all in their path. This marked the end of the Classical and the beginning of the Hellenistic periods, when Greek culture and influence was spread to most of the known world.

History, however, is doomed to repeat itself and many, including the Romans themselves, considered the conquest of Greece to be an act of preservation rather than an act of destruction. The century following the battle, Pydna saw Rome extend her aegis across the Mediterranean and assume dominion over the remaining independent Greek kingdoms. The Caesars had come and stamped the world with their autocratic and indomitable will.

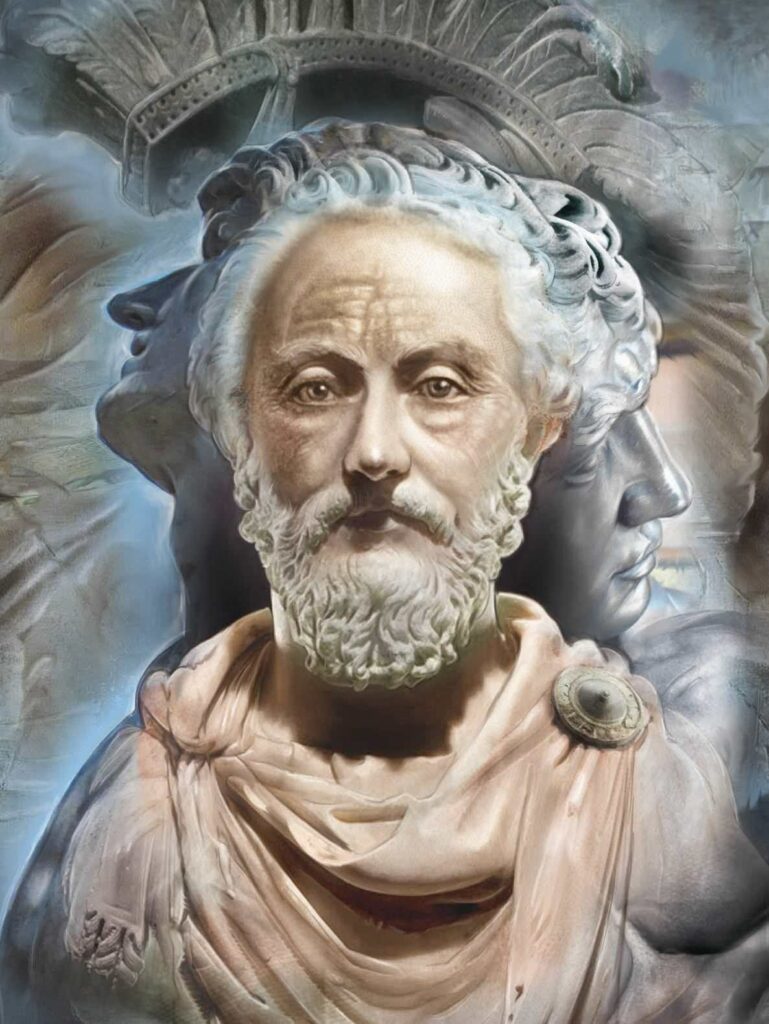

At Chaeronea, which lies east of Delphi, Ploutarchos was born into this world in the year 46 CE. More commonly referred to as Plutarch, he was the scion of a wealthy family and grew to serve his hometown as magistrate. He also spent the last 30 years of his life as high priest at Delphi. Significantly, he was also a prolific author, with much of his surviving work extant and considered extremely important to our understanding of Greco-Roman history.

Plutarch’s magnum opus is known as the Parallel Lives and was, for lack of a better term, a best-seller even in his own time. More a moralizing biographer than historian, Plutarch compared the lives of 23 prominent Greeks with the same number of Romans – all historical figures of renown. It was his way of reconciling the now subservient Greeks, whose culture was still very prominent, with their Roman overlords. We have more in common than in opposition, Plutarch’s works seem to say, an issue tackled by many Greek authors of the period — a poignant lesson for us today. Many of the details recorded within the Lives are found in no other source. The Life of Alexander, for example, remains only one of a handful of tertiary sources regarding the great conqueror.

Plutarch mentions a great many of his sources and clearly spent a lifetime compiling his research. Salient to our topic, the lives of five Spartans received the attention of his agile and inquisitive mind. Quite possibly as reference material, Plutarch collected a great number of sayings of Spartan men, and, uniquely, of Spartan women as well. They’re known today as the ‘Apophthegms’. The word means a short, suitably laconic aphorism.

These sayings, like the Spartan lives recorded by Plutarch, are an invaluable resource for anyone interested in a deeper dive into the history of Sparta. Apocryphal, anecdotal and sensational, they nonetheless convey the spirit of the Lacedaemonian men and women.

Below is an example of one, accompanied by some historical context and a description of the saying’s participants.

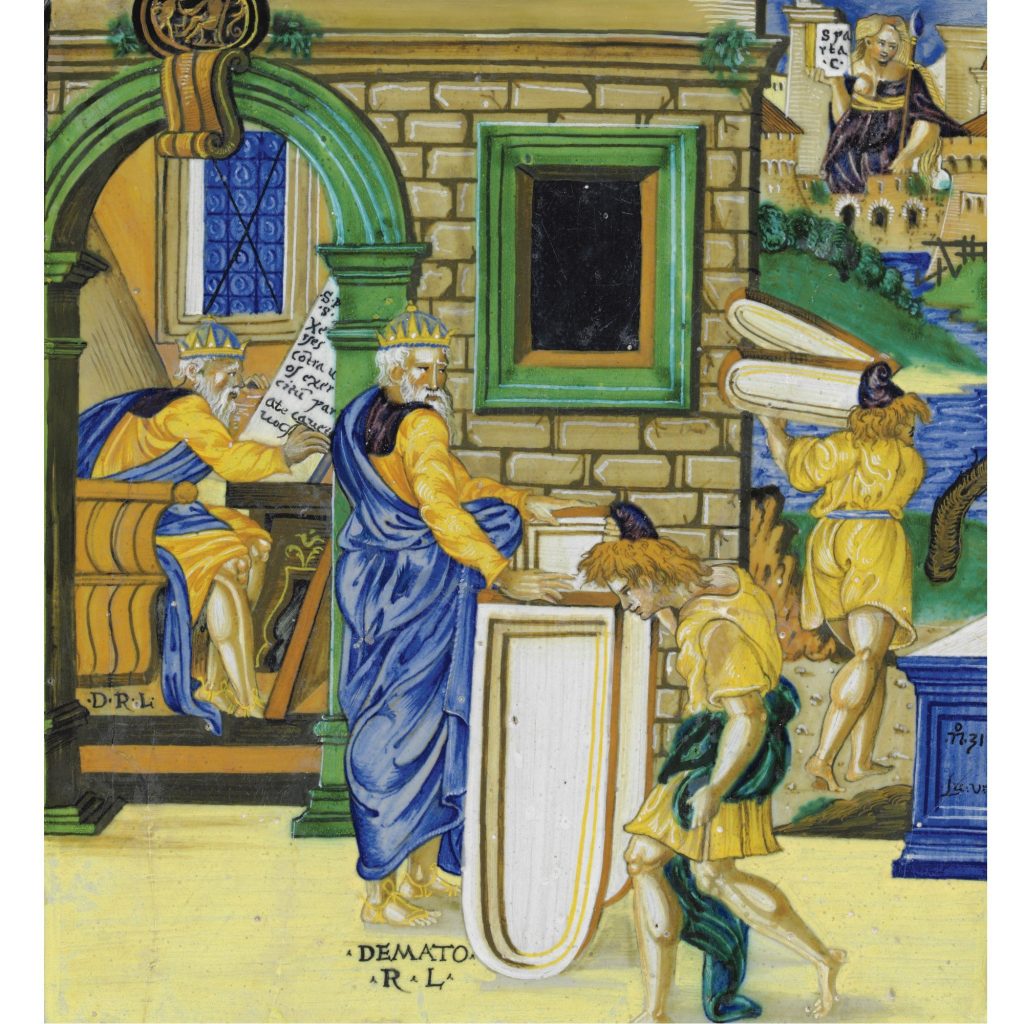

DEMARATUS #1

EURYPONTID, KING OF SPARTA 515-491 BCE, TIME OF DEATH UNKNOWN THOUGH POST 480 BCE

After Orontes had conversed with him rather rudely and somebody remarked: ‘Demaratus, Orontes has treated you rudely,’ Demaratus replied: ‘He has done me no wrong, since it’s those who converse to curry favor who do harm, not those who show enmity.’

This saying, attributed to the deposed king of Sparta, Demaratus, deals intelligently with the attempt of the unknown speaker to raise his ire. In Lacedaemon, the Spartiates respected direct language — one of the many things impressed upon them during their brutal Agoge soldier’s training. Although Orontes appears to have insulted the king, in the mind of Demaratus the far more pernicious threat lay within the honeyed and obsequious attempt to gain his reaction.

Coming to the junior Eurypontid throne in 515 BCE, Demaratus had as his colleague in the senior Agiad line Cleomenes the first. Cleomenes was perhaps the most autocratic ruler Sparta endured since the dilution of kingly power under which the dual monarchs became merely part of the Gerousia — the council of elders. This weakening of power, however, meant nothing to Cleomenes, who through experience and prestige dominated Spartan policy during his long reign. This is typified by the fact that when the tyrant of Miletus, Aristagoras, came to Sparta seeking aid on the eve of the Ionian revolt, the father of history records that it was Cleomenes alone who decided to abstain from conflict with Persia. Interestingly it was his daughter, a young Gorgo, who truly helped the king see the treachery behind Aristagoras’’ plea.

In the Histories, Herodotus has Cleomenes appear as the preponderant power within Laconia. The account of his reign provides valuable insight into the power struggles in the upper echelons of the city’s ruling elite. Any apparent unity or harmony that was perceived from outside Sparta was, at best, only half of the story. Factionalism was an inherent part of the system legendarily instituted by Lycurgus and in Demaratus’ time he was the natural nexus for the anti-Cleomenes party.

The two kings first clashed seriously in the year 506 BCE, when Demaratus unsuccessfully attempted to frustrate Cleomenes’ plans to install an Athenian aristocrat, Isogoras, as tyrant of Athens. Unthwarted, Cleomenes took the city’s power center, the Acropolis, by force. There he enthroned Isogoras as a puppet controlled by Sparta.

This state of affairs lasted barely three days before the indignant Athenian populace rose up, besieged the foreign force polluting the holiest sites of Athena and forced them into submission – thus reestablishing democracy. Cleomenes was given clemency along with Isogoras and his army, but three hundred of his closest allies were executed to quell the bloodlust of the ever-vengeful Athenian citizenry. This quick and complete reversal of fortunes was believed, at the time, to have Demaratus’ hand in it. Regardless, the event solidified the enmity between the two rulers of Sparta.

The next decade-and-a-half saw an increasingly powerful Cleomenes run roughshod over Demaratus, the Gerousia and Ephorate. However, in 491 BCE, the year prior to the battle of Marathon, his luck ran out. In preparation for the upcoming invasion, the Persian king Darius sent harbingers of his doom to the Greek cities in his path, demanding earth and water—customary tokens of submission.

The powerful island of Aegina, an ally of Sparta, was one of the many that submitted. In response, the thoroughly anti-Persian Cleomenes hatched a scheme to arrest the major collaborators. Demaratus contrived to successfully undermine his rival’s plans. Now thoroughly piqued, the Agiad king decided to rid himself of the royal thorn in his side, and enacted a two-pronged attack on the legitimacy of Demaratus’’ kingship.

First, Cleomenes convinced a younger man of the Eurypontid house, Leotychides, to lay charges against Demaratus, suing for his deposition with accusations of questionable parentage. Secondly, he bribed the Delphic oracle into pronouncing it was Apollo’s will that his rival should no longer hold the title of king. These accusations proved too much for the Spartans. Demaratus was relieved of his title and Leotychides assumed the Eurypontid throne.

Dethroned, Demaratus was left with few options. He took one common for disaffected aristocrats in ancient Greece — he medized. By going over to the Persian side, he was presumably gifted lands, title and celebratory status, serving in the courts of first Darius and then Xerxes.

Demaratus also received, with more than a little irony, a front-row seat to see his former countrymen’s valor as he accompanied the invading Persian forces on their invasion of Greece in 480 BCE. This was Xerxes’ great attempt to bring the troublesome Greeks to heel, while simultaneously erasing the stain to his fathers’ dishonor for his defeat at Marathon a decade before.

Demaratus played a seminal role in the Histories, serving the function of wise foreign advisor to the often-exasperated great king of Persia. He famously told his benefactor—who was surprised at the appearance of Spartan-led resistance in the pass of Thermopylae:

“One against one, they are as good as anyone in the world. For though they are free men, they are not entirely free. They accept the law as their master. And they respect this master more than your subjects respect you. Whatever he commands, they do. And his command never changes. It forbids them to flee in battle, whatever the number of their foes. He requires them to stand firm — to conquer or die.”

They were words Xerxes would see come to fruition soon enough.

Demaratus’ fate following the invasion isn’t known, though presumably he returned to Asia Minor and his estates within the Persian empire. In regards to Cleomenes, the architect of his exile, Demaratus may have had the last laugh. His former co-king’s impiety in bribing the oracle had come to light by 490 BCE, resulting in him losing his vice-like control over Sparta. From there, Cleomenes went stark-raving mad, supposedly due to his partaking of wine neat – i.e., drinking the unwatered ancient variety widely believed to cause insanity.

Subsequently imprisoned in stocks, his jailors left an apparently reliable Helot in charge of the raving King. Clearly, he had not lost his powers of persuasion and soon convinced the slave to give him a knife, with which he sliced himself to ribbons, committing suicide. In the minds of the ancient Greeks, it was an end sufficiently sticky for sacrilege. Whilst Demaratus showed antipathy for his royal partner, it was Cleomenes who would, in Demaratus’ words, “converse to curry favor” with Delphi, ultimately causing the real harm.

Steven Whitehead is the host and producer of the Spartan History Podcast. Have a listen to his show here: https://www.spartanhistorypodcast.com

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.