Thucydides, the ancient Greek historian and general, is most famous for his narrative of the

Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC). The war was a struggle between Athens and Sparta and led to all-out war between the Greek city states as they sided with one or the other.

Thucydides documented not only the military and political decisions that were decisive during the war, but in so doing captured the darkest depths of human nature itself. He closes his preface to The History of the Peloponnesian War with the following remark:

This history may not be the most delightful to hear, since there is no mythology in it. But those who want to look into the truth of what was done in the past—which, given the human condition, will recur in the future, either in the same fashion or nearly so—those readers will find this History valuable enough, as this was composed to be a lasting possession and not to be heard for a prize at the moment of a contest.

Bust of Thucydides, the ancient Greek historian and general.

Indeed, it is not the most delightful history to hear, not simply because there is no mythology in it, but because the violence carried out upon Greeks by fellow Greeks is so vicious and reflects all too well the violence held just beneath the surface within us today.

Yet, if such violence is part of our condition, part of our very nature, then we would do well to listen closely to the stories Thucydides passes onto us, so that we might avoid their recurrence.

Through the course of his narrative of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides shows again and again that human beings are motivated primarily by fear, ambition, self-advantage, and a desire to rule over others. He sees these motives at play throughout the war between

Athens and Lacedaemon (area of ancient Greece that comprised the city-state of Sparta), leading to some of the worst mistakes and injustices carried out on both sides.

Origins of the War

The origin of the war, according to Thucydides, was rooted in fear. Though the Lacedaemonians gave other reasons, Thucydides claims that fear was the underlying motive. As he put it, “the growth of Athenian power… put fear into the Lacedaemonians and so compelled them into war.” This was also one of the reasons that other cities joined Sparta, “some out of the desire to be set free from their empire, and others for fear of falling under it.”

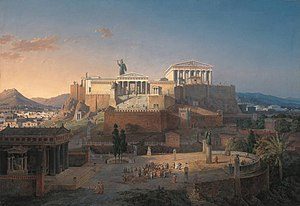

The Acropolis of Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846)

A similar analysis is made concerning the Athenian empire. The Athenian ambassadors at Sparta, after hearing the complaints against them by representatives from Corinth, Aegina, and Megara, make a speech of their own.

In this speech they claimed that, after taking the lead and finishing the war against the Persians (Greco-Persian Wars, 492-449 BCE), “we were compelled to develop our empire to its present strength by fear first of all, but also by ambition, and lastly for our own advantage.” They went on to say that, “If we have been overcome by three of the strongest motives—ambition, fear, and our own advantage—we have not been the first to do this. It has always been established that the weaker are held down by the stronger.”

The Athenians, despite the fear and anger aroused against them (as Master Yoda once put it, “Fear leads to anger”), claimed that they could not be accused of anything more than acting in accordance with the nature of things.

The Plague

In the second year of the war

a plague struck Athens, one so terrible Thucydides describes it as “too severe for human nature.” With the spread of disease and desperation came lawlessness. The quick reversals of fortune, Thucydides claims, led men to dare “to do freely things they would have hidden before—things they never would have admitted they did for pleasure.” He continues, writing:

And so, because they thought their lives and their property were equally ephemeral, they justified seeking quick satisfaction in easy pleasures. As for doing what had been considered noble, no one was eager to take any further pains for this, because they thought it uncertain whether they should die or not before they achieved it. But the pleasure of the moment, and whatever contributed to that, were set up as standards of nobility and usefulness. No one was held back in awe, either by fear of the gods or by the laws of men: not by the gods, because men concluded it was all the same whether they worshipped or not, seeing that they all perished alike; and not by the law, because no one expected to live till he was tried and punished for his crimes. But they thought that a far greater sentence hung over their heads now, and that before this fell they had a reason to get some pleasure in life.

The Plague of Athens, Michiel Sweerts, c. 1652–1654

This is what Thucydides meant when he said the plague was too severe for human nature. The devastation wrought by the plague brought forth their true tendencies that, before then, had remained dormant, held down by fear of the gods and the laws of men.

These two checks on our true nature had been rendered powerless… what became feared most was death by plague. And this fear, along with our tendency to pursue our own advantage, led people to seek immediate satisfaction in base pleasures. The very things that had once been considered noble, Thucydides tells us, were abandoned for such base pleasures.

During the plague even the great citizens of Athens succumbed to these inner tendencies—tendencies that, in better times, lurk only beneath the surface.

The Corcyrean Civil War

The civil war that took place on Corcyra is another example of our inner tendencies being brought to the surface. This civil war was between Corcyrean democrats and oligarchs, the former sympathetic to Athens and the latter sympathetic to the Lacedaemonians.

Once again, all became permissible. As Thucydides tells us, “there was nothing people would not do, and more: fathers killed their sons; men were dragged out of the temples and then killed hard by; and some who were walled up in the temple of Dionysus died inside it.” In the same way that what was considered noble was flipped on its head during the plague, the valuations of actions and traits were reversed:

Ill-considered boldness was counted as loyal manliness; prudent hesitation was held to be cowardice in disguise, and moderation merely the cloak of an unmanly nature…In brief, a man was praised if he could commit some evil action before anyone else did, or if he could cheer on another person who had never meant to do such a thing.

How many of us have seen, in these divisive times, individuals praising what they once condemned? Defending actions they would otherwise find abhorrent? In our more reflective moments, have we not seen this within ourselves?

This copper engraving by Matthaus Merian depicts the Athenian naval victory near Corinth over the Corinthian and Spartan fleet around 430 B.C.E. Photograph by akg-images/Newscom

Thucydides goes on to tell us that family ties were trumped by party loyalty, piety was all but forgotten, and that those who tried to remain neutral were attacked from both sides. How could this happen? Thucydides explains:

The cause of all this was the desire to rule out of avarice and ambition, and the zeal for winning that proceeds from those two… And though [each party] pretended to serve the public in their speeches, they actually treated it as the prize for their competition; and striving by whatever means to win, both sides ventured on most horrible outrages and exacted even greater revenge, without any regard for justice or the public good.

Does this state of affairs sound at all familiar?

The War Within

The cause of the evils of war, according to Thucydides, is not war itself, but us. If we were other creatures with a different nature, perhaps war would not be so terrible, or not occur at all.

When he describes fear, ambition, self-advantage, and our desire to rule over others, as our natural tendencies, he is not saying that we always act from these motives. For him, these always lie within us but are brought to the surface by disastrous events or great periods of hardship:

In peace and prosperity, cities and private individuals alike are better minded because they are not plunged into the necessity of doing anything against their will; but war is a violent teacher: it gives most people impulses that are as bad as their situation when it takes away the easy supply of what they need for daily life.

Pericles’ Funeral Oration (Perikles hält die Leichenrede) by Philipp Foltz (1852)

William Tecumseh Sherman, that great general of the Union Army, made famous the phrase that “War is hell.” Albert Camus, in his Notebooks, jotted down the following: “We used to wonder where war lived, what it was that made it so vile. And now we realize that we know where it lives… inside ourselves.”

Thucydides would nod in agreement with both. What makes war hell is that it emanates from the hell within us, always waiting for the right to circumstances to unleash its fury. Or, as the Joker puts it in the Dark Knight,

You see, their morals, their code, it’s a bad joke. Dropped at the first sign of trouble. They’re only as good as the world allows them to be. I’ll show you. When the chips are down, these… these civilized people, they’ll eat each other.

Human nature is laid bare in the events Thucydides describes because they reveal to us our innermost tendencies, what lurks beneath the surface at all times. In the right conditions these tendencies stay beneath the surface but, when put under stress or hardship, they all too readily are unleashed and wreak the type of havoc witnessed during the Peloponnesian War. And, importantly for Thucydides, such events will always have these effects, to a greater or lesser degree, so long as human nature remains the same.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.