By Nicole Saldarriaga

Close your eyes. Take a deep breath, and imagine that on the inhale, your nose and mouth are flooded with the smell of mold, dank water, and even worse, what is unmistakably the smell of blood—a lot of it. You are in The Labyrinth. The light in its dizzying corridors is murky, almost non-existent, and the combination of fear and darkness makes it difficult for you to move—but you stumble along anyway, quickly as you can, your breath sharp and painful in your throat, because somewhere in the darkness behind you, there are footsteps…heavy ones. You are being hunted.

What you just imagined comes straight out of an Ancient Greek myth—one with which many people are familiar: the myth of the Minotaur.

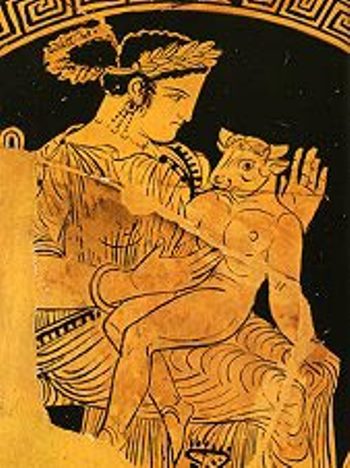

The Minotaur, according to legend, was the very definition of grotesque. He had the body of an enormous, powerful man, but instead of a human face, he had the head of a twisted and deformed bull. Though the Minotaur sounds like a Frankensteinian experiment gone wrong, he is actually the biological offspring of a woman and a bull.

The Minotaur, according to legend, was the very definition of grotesque. He had the body of an enormous, powerful man, but instead of a human face, he had the head of a twisted and deformed bull. Though the Minotaur sounds like a Frankensteinian experiment gone wrong, he is actually the biological offspring of a woman and a bull.The story goes something like this: Minos, the powerful king of Crete, prayed to Poseidon, requesting that the sea-god send him a white bull from the sea. The creature was meant to be a sign of Poseidon’s support and approval of Minos’s rule, and it was Minos’s duty to sacrifice the animal in Poseidon’s name in order to show his gratitude for the divine endorsement. The bull, however, was incredibly beautiful—so beautiful that Minos decided to keep it. He sacrificed a different bull instead, hoping that Poseidon wouldn’t notice the difference.

Of course, the god could not be so easily fooled; and he chose to punish Minos in a very interesting way. Poseidon caused Minos’ wife, Pasiphae, to fall in love with the bull. Overcome with lust for the animal, she had Daedalus—a master inventor—construct a kind of hollow wooden cow in which she could hide. Pasiphae had this false cow placed in the pasture where the bull would graze, and the animal, fooled by the disguise, mounted the wooden contraption—with Pasiphae inside it. Some months later, she gave birth to the Minotaur.

So—what do you do with a half-human, half-bull child—and one whose only source of nourishment seems to be human flesh? Minos, enraged and more than a little ashamed by the whole situation, decided to imprison his half-son forever. He had Daedalus build a labyrinth—one so vast and confusing that it was virtually impossible to escape—and he abandoned the Minotaur in its depths.

Fast forward a few years, and Minos wages war on Athens. According to the myth, the war was a direct result of the murder of Androgeus, Minos’ legitimate (and human) son. Some say Androgeus was killed by the young men of Athens, who were jealous of his brilliant performance at the Panathenaic Festival (a kind of pre-cursor to the Olympic games), and other sources claim that he was killed by a bull on the direct orders of Aegeus, king of Athens.

Whatever the reason, Crete and Athens went to war, and Crete emerged the victor (keep in mind that the myth is set during a period of history when Athens was still a disorganized little conglomerate of cities, and Crete—largely thanks to its impressive navy—was easily more powerful than Athens and most of the other surrounding communities).Victorious but not yet satisfied, Minos then forced Athens to send him a tribute (some sources say yearly, while others say every nine years) of seven young virgin men and seven young virgin women—all of whom would be sacrificed to the Minotaur. This continued until the legendary Theseus, son of Aegeus, conquered the Labyrinth with a simple ball of twine and battled the Minotaur, finally killing the beast.

So goes the myth; and it certainly would not be incorrect to call it a crowd favorite. The labyrinth, in particular, remains a popular motif in horror stories and psychological thrillers. There is something about the idea of being trapped in a maze, all sense of direction lost, which triggers an instinctual fear in us. Throw in a blood-thirsty monster, and you’ve got yourself one hell of a nightmare.

So goes the myth; and it certainly would not be incorrect to call it a crowd favorite. The labyrinth, in particular, remains a popular motif in horror stories and psychological thrillers. There is something about the idea of being trapped in a maze, all sense of direction lost, which triggers an instinctual fear in us. Throw in a blood-thirsty monster, and you’ve got yourself one hell of a nightmare.But what happens when you deconstruct the myth? Tracing the legend back to its possible origins may not make it any less deliciously chilling, but it’s certainly worth doing, if only so that we get a better glimpse of the cultural climate at the time.

The first important thing to keep in mind is that the myth of the Minotaur is an entirely Athenian one. On some level, then, the myth may have been a way for Athenian citizens to process their feelings toward the Minoans on Crete (think of it as a “well, they may have been more powerful than us but their queen slept with a bull and they did awful things like feed people to a monster” kind of thing). This is supported by the fact that King Minos, in other myths and sources, is famous for wisdom, shrewd judgement, and a rule which led to a flourishing of culture on Crete. That is quite a contrast to the Athenian myths, which painted Minos as a terrifying dictator while singing the praises of Athenian heroes (like Theseus).

The Athenians could have come up with any crazy rumor to defame the Minoans, however. Why did they land on a man-eating bull-monster in a labyrinth, specifically?

Ruins of the palace at Knossos

Ruins of the palace at KnossosSome possible answers to that question were uncovered about a century before our time. In 1900 CE, an archeologist named Sir Arthur Evans began to dig on Crete in what his colleagues considered a demented and ridiculous search for the city of Knossos—a city that was considered the possible home of King Minos and largely legendary. Surprisingly, Evans found it. As he dug, he uncovered the ruins of an elaborate palace that, all-told, would have had something like five stories and a thousand rooms laid out in a winding, seemingly random order. Strangest of all, the palace had no hallways—each room was connected to the next by small passageways, which resulted in a rather dark, labyrinthine structure (see where I’m going with this?). To mainland Greeks (such as the Athenians), this style of architecture would have seemed more than bizarre—it probably would have seemed threatening. It’s not difficult to believe that this could have inspired the myth of a dark, dungeon-like labyrinth on Crete.

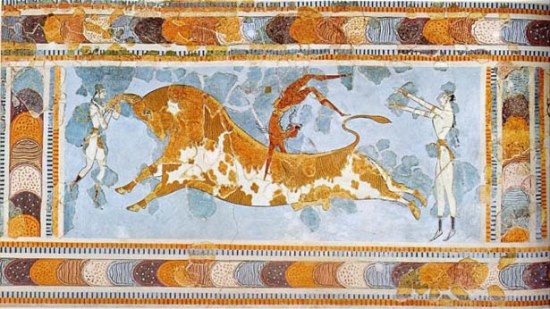

So why the bull? Traditionally, in ancient societies the bull was often seen as a sacred symbol of power, strength, and male virility. Accordingly, bull worship seems to have been a central aspect of religious life in Knossos. Numbered among the artifacts found during excavations of the site are several bulls, bull horns, and frescoes depicting bulls. It’s also possible that the Minoans engaged in a dangerous sport called taurokathapsia, often referred to in English as “bull leaping.” In theory, young men brave (or stupid) enough to participate in this sport would take a running jump at a charging bull, grab its horns, and use the bull’s instinctual head-snapping motion to propel themselves into an acrobatic leap over the bull’s back.

So why the bull? Traditionally, in ancient societies the bull was often seen as a sacred symbol of power, strength, and male virility. Accordingly, bull worship seems to have been a central aspect of religious life in Knossos. Numbered among the artifacts found during excavations of the site are several bulls, bull horns, and frescoes depicting bulls. It’s also possible that the Minoans engaged in a dangerous sport called taurokathapsia, often referred to in English as “bull leaping.” In theory, young men brave (or stupid) enough to participate in this sport would take a running jump at a charging bull, grab its horns, and use the bull’s instinctual head-snapping motion to propel themselves into an acrobatic leap over the bull’s back. The famous “Bull-leaping fresco”

The famous “Bull-leaping fresco”A famous fresco on the wall of the palace at Knossos seems to support this theory, but it could also represent a variety of different things, and there just isn’t enough evidence to prove that the sport was performed in that way or even really existed. What is clear is that bulls were important to the Minoans, and that Minoan civilization had an interesting, sacred, and almost personal relationship with the animal. This love of bulls could have been carried over into Athenian rumor, and could be considered a source for the idea of Pasiphae’s unusual lust and the idea of the Minotaur itself.

The notion that young men and women were sacrificed to the Minotaur could also have arisen from a factual cultural practice on Crete. Excavations in the 1980s in villages right outside of Knossos led to the discovery of mass gravesites filled with bones—the bones, in fact, of children. Marks on the bones indicate not only that the children suffered a violent death, but also that they were butchered in much the same way one would butcher a lamb. All evidence seems to point toward ritual human sacrifice.

Considering all these aspects of life on Knossos, it isn’t difficult to believe that the Athenians, who had once been firmly under Crete’s thumb, would have taken the little bit of information they had, mixed it with rumor, and inflated it until, in their storytelling tradition, Crete had become a place of irreverence for the gods, bestiality, human sacrifice, horrifying labyrinths, and monsters.

To the Athenians, who valued reason above almost anything else, it was a way of proving to themselves that, despite their humble beginnings, their reason and civility could do nothing but triumph over Crete’s perceived animalism and crudeness. Reason is always the most powerful weapon. The myth itself gives us clues that lead to this conclusion. While the Minotaur is the beast, the animal instinct and passion that live deep inside the labyrinth of every person’s mind, Theseus is reason, powerful enough to subdue those lingering bestial qualities. The ball of twine he uses to conquer the labyrinth (by tying it to the door and later following the twine to get out again) represents a beautifully simple answer to a seemingly insurmountable problem.

Reason, then, will always win out. It is (if you agree with the Athenians) the most powerful weapon we have against the monster that is buried somewhere deep inside us all.

So—close your eyes again. You are in the labyrinth. You are being hunted.

Are you ready?

One comment

When I was at Knossos in 2018, a fabulous guide suggested that Queen Pasiphae may have fallen for a foreign sailor or tradesman (my imagination conjured up an ancient Norsemen who was tall and blonde!). She became pregnant and gave birth to a child who looked much different from the small dark-haired and dark-eyed people of Knossos. Because he would clearly NOT belong to Minos, the child was outfitted with the headdress of a bull which he was forced to wear in public, for example in the royal box when the Minoans were gathered for athletic contests. The labyrinthian construction of Knossos, as well as the centrality of the bull to their culture made this idea so plausible to me that my eyes filled with tears. But then again, I am an emotional student of the ancients!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.