Written by Jocelyn Hitchcock, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

“Sing, O Muse, of the man of many devices…”

Line one of the Odyssey begins like so many in ancient literature, by invoking the muses or gods. It was a common practice to ask, thank, and implore the other-worldly forces for inspiration and guidance in writing and story-telling.

The muses themselves are generally split into two different generations: the “Elder” and the “Younger.” The Younger Muses are perhaps more widely known, as they were often represented on Mount Olympus or in the company of Dionysus and Apollo. Stories, music, and dance were all a part of their entertainment repertoire, performing in joy and in sorrow, as they were said to have been present even at the funerals of Achilles and Patroclus, lamenting the deceased and their honors in life.

It is the Younger Muses, as Hesiod referred to them in his Theogony, that Calliope, the muse of eloquence and epic poetry, belonged to. Calliope was the eldest of the muse offspring between Zeus and Mnemosyne (the goddess of memory), supposedly conceived on the first night of the partnership. Calliope was also the mother of Orpheus, fathered by Oiagros, the Thracian king, who caused “stones and trees to move” with his own singing.

Calliope is usually depicted with a lyre, tablet, or stylus, representing her written and verbal talents. She doesn’t usually appear by herself in stories, but with her sisters complementing one another.

Calliope, being the muse of eloquence, is naturally closely linked with the mortal world. It is said that she was the one who gifted kings with the ability to speak with grace and power when they were babies by anointing their lips with honey. In this way, when the babies grew up, they were able to “utter true judgments” and “would soon make wise end even of a great quarrel” (Hesiod, Theogony, 75).

Depictions in Art

As the muses as a whole were incredibly influential in the mortal and divine world, it comes as no surprise that they were depicted at length in classical art. Calliope, being considered the eldest, the muse at the helm of her sisters, was a popular subject. She is depicted on dozens of Athenian red figure vases, mosaics, and sculptures.

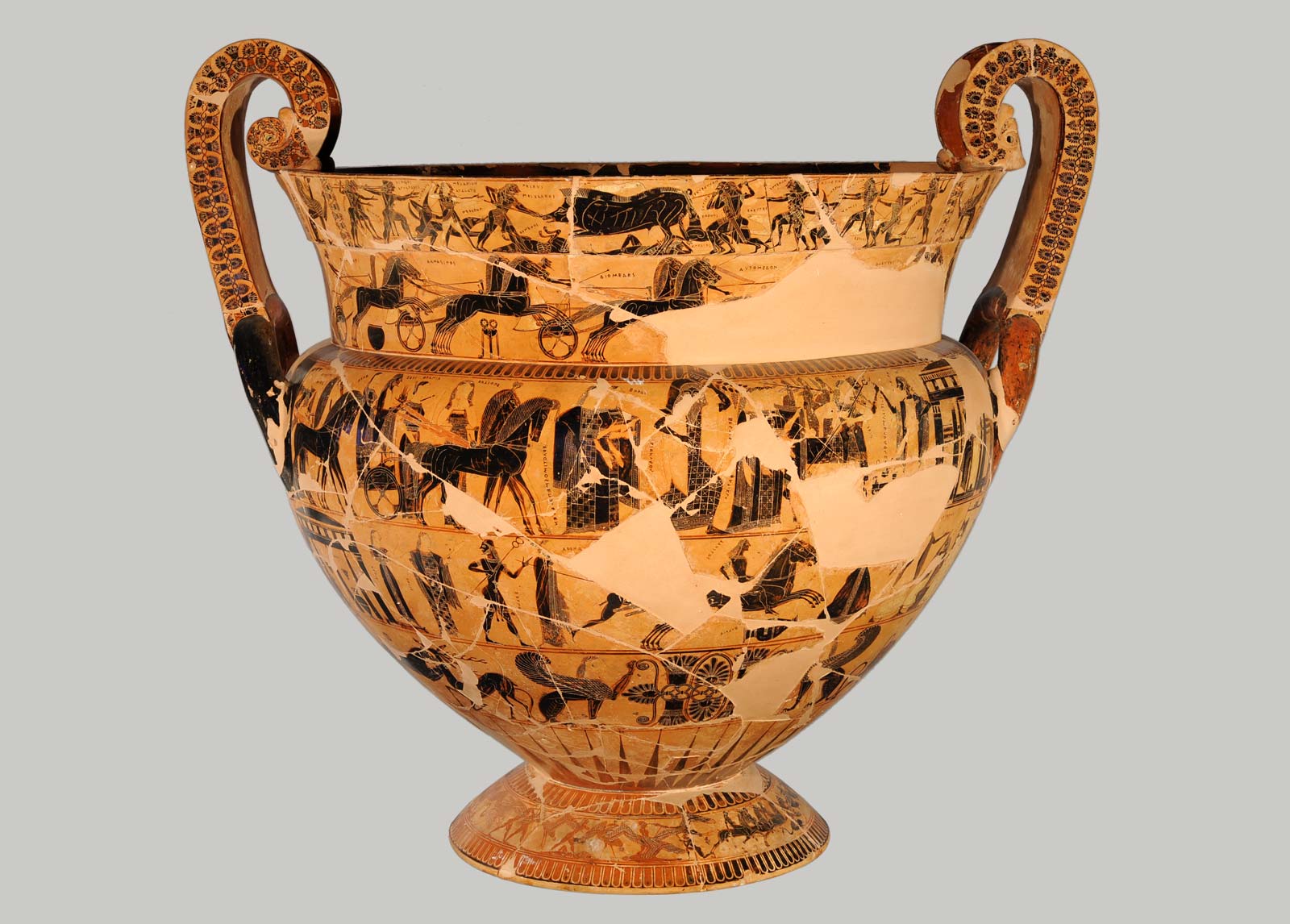

One famous depiction is on the Francois Vase, a large Attic volute krater produced by the artist Ergotimos around 570 BCE. You can see her identified by name on the upper belly of the vase next to two horses, Zeus, and Ourania, who Calliope leads the procession with. The other 7 muses are depicted behind Zeus. Seen frontally on the vase, Calliope occupies an interesting position of dominance.

In more recent art, such as the painting by Charles Meynier in 1798, Calliope is depicted as directly inspiring the Homeric epics. While she is not specifically named at the opening of epics—just a general ‘muse’ being used to invoke the ethereal realm—Calliope being the oldest, most prominent, and most associated with eloquence, makes it likely that she was the intended muse.

Other renderings of Calliope depict her in the classical style we are familiar with: flowing robes, a tablet or writing instrument, and austere but serene countenance.

Overall, the 9 Muses continue to be treated as a cohesive unit, operating in pursuit of a common goal. However, Calliope is presented and revered as one of the more prominent of muses, no doubt due to the fact that she is intimately tied to the Homeric epics and feats of leaders. She operates immediately behind the scenes, never far from the action.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.