It was the fifth century Athenian tragedians who recognised the brutal power of the Electra story. Despite being little more than a footnote to Homer, this torrid tale of a sister and brother (Orestes) taking revenge their mother (Clytemnestra) for the murder of their father (Agamemnon) is rich in dramatic content. In particular, Electra herself is a playwright’s dream: wronged, bitter, wrathful, erudite, hysterical, pathological, dangerous, righteous and female.

This may well be the reason why we have full, extant plays about her by Euripides, Sophocles and Aeschylus.

Euripides tackles her story in Electra, Sophocles in… Electra, and Aeschylus in a play called, of course…[ahem]… The Choephori. However, we’ll refrain from calling him a spoil-sport as his was the first of the three interpretations.

The Choephori of Aeschylus, part of his classic Orestria trilogy, was performed forty years before the dramas of the other two. It was seen as a benchmark for theatrical excellence, an intimidating marker thrown down to any young pretender.

It isn’t clear if Sophocles or Euripides were first in reinventing this tale of manic trauma, but both men were far more akin in their depictions of Electra than that of the old master.

Whilst the Electra of Aeschylus is provocative, hostile and vengeful, she shows these attributes passively, often by proxy through her brother Orestes. She worships her dead father, but knows her place as a woman in the social and heroic order.

Orestes and Electra

Her calls for revenge are real, but they obliquely fall short of inciting murder: “blood must match blood, and wrong with wrong” [473] is the closest she gets to anything like real participation. In fact, once the action begins in earnest, we see no more of her and the dirty work is left to Orestes.

Electra, as seen by Sophocles and Euripides, was a little bit different. Their treatment of her was not only brave, but also dangerous and necessary.

Rehashing a classic is always fraught with peril. The audience knows the story backwards. They want justice to be done to the ‘original’, but they need something fresh and new to keep them in their seats.

Sophocles shows Electra going through a process of willful over-mourning for Agamemnon. This would have been sickening for a Greek audience as, for them, mourning wasn’t merely the stages of coming to terms with emotions, but a codified, public display of religious rites.

He portrays her as a lovelorn widow, not as a bereaved daughter. It is from this depiction that Carl Jung developed the “Electra Complex”, the feminine version of the more famous Oedipal one.

Hubris and incest are rife in Sophocles’ Electra. They require the context of the time to be fully comprehended, but he undoubtedly succeeded in taking a play about matricide and burdening it yet further with sin and shame that would have caused many a furtive glance over the family breakfast table.

Euripides, the enfant terrible, could not resist going a step further. But what could possibly go further than allusions to incest? For the ancient Athenians it would be an inversion of the gender roles.

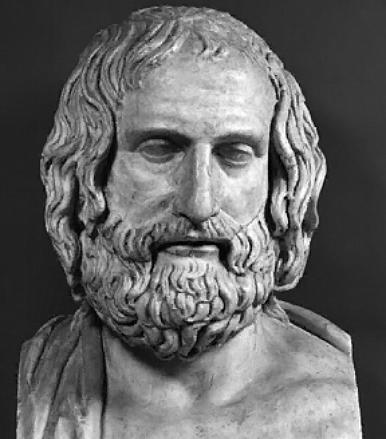

Bust of Euripides

Euripides emasculates Orestes in front of the Athenian crowd. The great heroic Orestes, a hero with links to Athens!

It is typical of Euripides to distort and degrade, reverse and revile. Little boys in the street ‘playing’ myths would cry “I’ll be Orestes and you be Aegisthus” “No! I’LL be Orestes and YOU Aegisthus”. After Euripides was through with them, they wouldn’t even know which way round to hold the blade.

It is this Electra, this wild and willful woman, who goes beyond the one previously depicted. Sophocles’ Electra rejects femininity, and thus the fabric of social order, but only in words, not in deeds: “Call me what you will – vile, brutal, shameless” [606].

The Electra of Euripides is wild and volatile, a confusion of extremes, not to mention a spouse of a poor and pathetic peasant.

However, it is not these that make her so low, so base, so… Euripidean.

It is her intelligence and with it her challenge to the status quo. A challenge which would make every Athenian with a strong wife sit slightly less comfortably in his seat.

With this Electra, Euripides directly mocks Aeschylus as a technical student of theatre who never bothered to study human psychology.

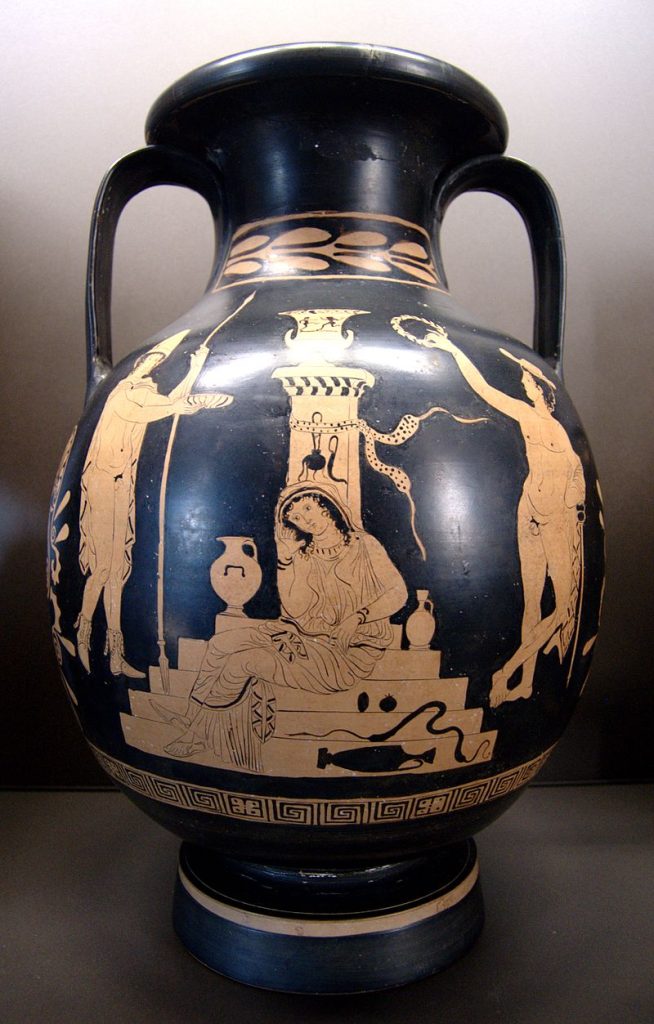

Orestes, Electra and Hermes at the tomb of Agamemnon, lucanian red-figure pelike, c. 380–370 BC, Louvre (K 544)

In Aeschylus’ The Choephori, Electra identifies her long lost brother through his (and her) similar hair, footprint and his baby clothes. Recognition scenes were not merely well-established, but more or less demanded by the Athenian public.

Euripides is ruthless in his dismissal of such trite conventions:

“You’ll find many with similar hair who are not of the same blood” [532] “brother’s and sister’s feet would not be of the same size” [538] “He wouldn’t now be wearing the same cloak he had in infancy” [570]

True, Euripides may have simply been hoping to gain a cheap laugh from an eager and merry audience. However, it would absolutely be true to his character if he were actually attempting to break the rigid structure of Greek theatre, not in its mechanics, but in its humanity and emotion.

He wanted to scream to his public that this was not a princess seeking vengeance, but a woman in pain. A brilliant, damaged, vulnerable, destructive vehicle of righteousness. A woman… No! A person prepared to inflict damnation and suffer eternal scorn. A vessel welling with the rage of love that never had the opportunity to be unrequited.

She is the killer.

Orestes dared not look, he held his cloak over his eyes like a little girl afraid of a storm [1222]. It was Electra’s hand, the hand of power, that clasped that of her brother as the blade slid jaggedly into their mother’s throat.

Orestes is a frail and fragile figure. A pathetic excuse for a man, for a hero, and for a Greek.

It is Electra who restores honour to her household, who butchers the unworthy parent in cold, but worthy blood.

Electra and Orestes, from an 1897 Stories from the Greek Tragedians, by Alfred Church

Men of Athens were comfortable with stories of murder, incest, hate and hubris. These were common sins. Common enough that nobody needed to debate their evil and illegality. However, the idea that a dominant woman, a crazed-genius, wanton-virgin, bile-inducing paradox of a creature could be in their midst, if only theatrically?

That was too much to take.

That was really worth being worried about.

That was really just typical of Euripides.

One comment

Hello,

I’d like to thank you a lot for your great website, newsletters. I also follow you on Facebook. I read Aeschylus’ Electra few days ago, and I inted to read the other two plays. I’m a bit surpired that I didn’t find in those old plays warm family relationships; Moreover, the hatred was more evident that the love between parents, childen, and siblings (In most of the plays I read they look more like strangers living together. How was the idea of Matricide received by the audience then?

Thanks and best regards

Maan Kawas

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.