By Rodrigo Ferreyra, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

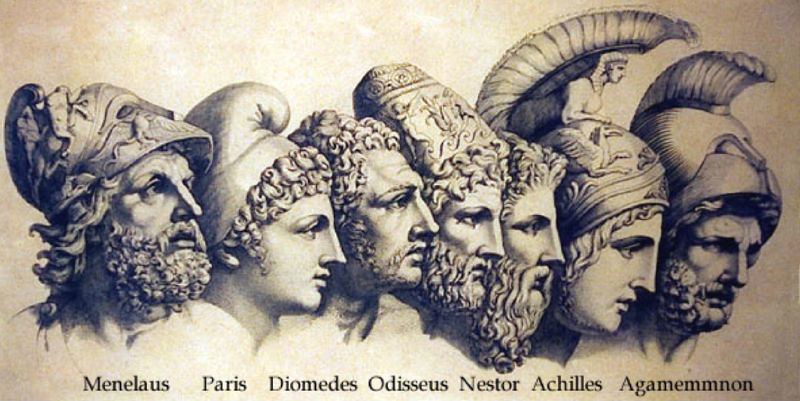

We are all familiar with Homer’s Iliad. We know about the Trojan War, the romance between Paris and Helen and the mighty Olympian gods. Most of all, we know the heroes. Whether it is Achilles, Odysseus or Ajax, they all possess outstanding characteristics such as bravery, physical skill, and virtue.

But we must also acknowledge that these Homeric heroes did not enjoy these attributes by mere chance. They, in fact, were conceived in this way as embodying another group of individuals, one which was to be portrayed as close to the gods.

In Homer’s Greek, Heroes meant lord, that is, the ruling class. In this way, the heroes were to some extent god-like, looking down on commoners, just as deities looked down on mortals.

Wellington Monument (Achilles)

The gods of the Iliad are also anthropomorphic, matching a rational and human notion of the divinity. Yet, unlike us humans, these gods are not tied to fate. In the Homeric notion of fate, all human beings have their “good” and “bad” experiences predestined by birth, as well as their limitations as mortals. In this way, fate is inevitable, and trying to go against it is but an insolence to the gods.

But what about heroes/aristocrats? Well, it is in their fate to excel, as they do in the Iliad, both in leading their troops and in combat. Nonetheless, they are also fated to death. The goddess Hera says to Achilles:

your fate still stays the same, to die in war,

killed by a mortal and a god.

To which he responds:

I know well enough I’m fated to die here,

far from my loving parents. No matter.

I will not stop till I have driven the Trojans

to the limit of what they can endure in war.

Achilles’ approach to facing his fate matches the death for which aristocrats wished. This was a manly, beautiful, and valiant death in battle: the so-called kalos kagathos. It is in their fate to achieve it. The nobles, after all, are inferior to the gods, who in turn, appear jealous of these mortals’ bravery.

At the same time, in the Iliad heroes can even succeed (although shortly) in transgressing their limitations as mortals. For instance, the Achaean hero Diomedes, with the help of the gods, goes as far as hurting Aphrodite and Ares. As something unthinkable for a mortal to do, Diomedes’ transgression of his fate implies him to have great power. As such, only a very few capable, powerful individuals can transgress their mortal limitations. Who? The heroes, that is, the aristocracy.

In this sense, “fate” in the Iliad is also present with another message: to keep in line those who dare against the ruling class. We are said that not everyone is equal. The composition of the Iliad coincided with a warrior noble class that controlled both the Greek land and wealth.

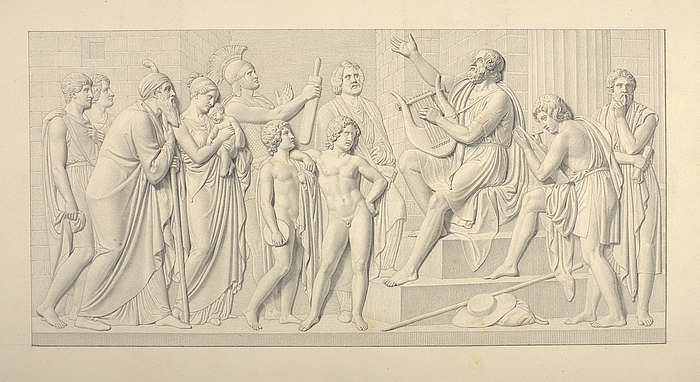

This was certainly a message they wanted to communicate not to us, but to their community. The Iliad, as well as the other parts of the “Epic Cycle”, came from an oral tradition. On the one hand, the poem’s structure is made to be read aloud and reach a wide and illiterate audience; on the other, these poems contain and communicate, above all, tradition. As such, the narrative seeks to show the story not as a past event, but as a mirror to the present world, the very same in which its listeners live.

In this way, the aristocratic presence in the Iliad is not a minor component. It underlies the very culture on which the poem was conceived and to which we must dive into to understand both the story and people who heard it.

No comments

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.