By Katherine Smyth, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

Down, down below the imperial Palace of Knossos, the capital of Crete and home to King Minos, legend has it that there lurks a mythical beast. A beast so terrible, so ferocious, that it could not be allowed to see the light of day. Contained within a maze, and fed by sacrificial rites, it is doomed to a storybook ending.

Minotaur bust, (National Archaeological Museum of Athens)

The Backstory to the Minotaur

The tale of the Minotaur has been popular throughout the ages; it dates back to Classical times and has a mythic base. Legend has it that the Minotaur was born as a result of Queen Pasiphae’s coupling with another mythological beast, the Cretan Bull. But, how did this happen?

Back in Crete’s early days, King Minos sought to assert his right to the throne over his brothers. As such, he prayed to the god Poseidon to send forth a magnificent bull, the Cretan Bull. Should the god grant this plea, Minos would sacrifice the bull in Poseidon’s honour in order that the deity would declare Minos’ right as ruler.

Pasiphaë and the Minotaur, Attic red-figure kylix found at Etruscan Vulci (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris)

But when Minos saw the bull and its magnificent breeding qualities, he refused to keep his end of the deal. Angered by this treachery, Poseidon asked the goddess Aphrodite to bewitch Minos’ wife, Queen Pasiphae, to fall in love with the bull. Consequently, the Queen gave birth to a child that was both human and bull-like in appearance.

How the Minotaur Got His Name

King Minos, ever the one to make the most of a sticky situation then decided that rather than face the humiliation of an unfaithful wife and an illegitimate offspring; he would name the beast after himself.

The name is translated from ancient Greek; Μῑνώταυρος, it is a combination of ‘Taurus’ (ταύρος in Ancient Greek) meaning bull, and ‘Minos’, or Μίνως in A.G. However, in Crete the beast was also known by the name of Asterion. This is the name of Minos’ foster-father and the first King of Crete.

The Minotaur in the Labyrinth, engraving of a 16th-century AD gem in the Medici Collection in the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

After the Minotaur’s birth, the Queen attempted to nurse and raise him as a prince of Crete. Unfortunately, the beast developed an unnatural appetite that could only be satiated by human flesh. King Minos sought advice from the Oracle at Delphi, and upon his return, he had the craftsman Daedalus design and build a mighty cage that would contain the beast; the Labyrinth. There, near the Palace of Knossos, the Minotaur was incarcerated. He was fed on a strict diet of human sacrifices, which were supplied by the King of Athens as punishment for murdering Minos’ son, Androgeos.

The Death of the Minotaur

King Minos’ son, Androgeos, had entered the Panathenaic festival – an early form of the Olympics – and had won many events in the games. Jealous of the prince’s success, the people of Athens murdered him. Another version of Prince Androgeos’ demise holds King Aegeus responsible, as the King had sent the prince to kill the Cretan Bull, where it was now running amok in Marathon. Androgeos attempted to kill the bull, but was instead gored to death.

Enter the hero Theseus, son of King Aegeus, the ruler of Athens.

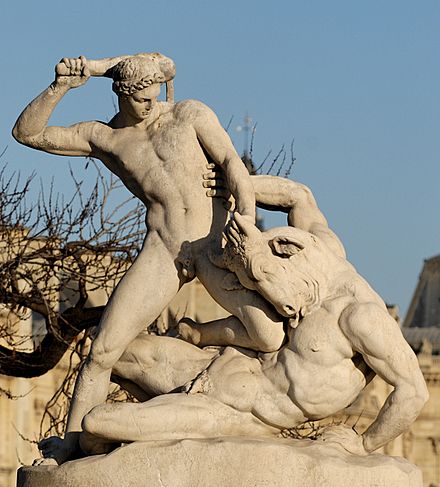

Theseus Fighting the Minotaur, 1826, by Jean-Etienne Ramey, marble, Tuileries Gardens, Paris

King Minos’ punishment to the people of Athens was brutal, every seven years Athenians were to select seven male youths and seven female youths who would be sent to Crete. There they would be expelled into the labyrinth and left to be hunted down by the Minotaur, who would kill and devour them one by one.

As the third sacrifice approached, some 21 years after the murder of Androgeos, Prince Theseus volunteered to end the debt by killing the monster. He sailed, with the 14 sacrificial youths, to Crete and presented himself to King Minos as part of the tribute. However, he caught the eye of King Minos’ daughter, Ariadne, who was instantly besotted with the hero. As the time of the sacrifice came, the prince and princess hatched a plot to ensure his safety – a length of twine that Theseus could unfurl to prevent getting lost in the Labyrinth.

Down into the dim and stench-laden labyrinth Theseus ventured, trailing the line as he went, hunting the monster that had eaten his fellow Athenians. Eventually, he found the Minotaur, combat ensued, and using his father’s sword, Theseus slew the monster before returning to the surface victorious. Theseus and Ariadne then fled Crete, leaving the Queen bereft and the King without retribution.

Ariadne and Theseus by Jean-Baptiste Regnault

The Minotaur’s Legacy

The story of the Minotaur has permeated throughout history and has continued to influence many artists throughout the ages. Most notably, the Minotaur appears in Dante’s Inferno when Virgil guides Dante as they prepare to enter the seventh circle of hell. Giovanni Boccaccio and Dante Gabriel Rossetti also wrote concerning the Minotaur. Picasso, Dali, and Rivera have also featured the beastie in surrealist artworks.

So, was the Minotaur real, or is it just a myth? This is something we’ll never be able to 100% confirm or deny. However, it’s worth remembering that the Minotaur had another name, Asterion. He was named after his foster-grandfather and Crete’s first king, Asterion I. Prince Asterion was the son of King Minos and Queen Pasiphae and his name means ‘starry’.

Minotaur, by George Frederick Watts

It is entirely plausible that Asterion may have suffered from a medical condition that manifested in a facial deformity, giving him a bull-like appearance. Some coins that were minted at Knossos from the fifth century bore the resemblance of a kneeling bull, and had a star-rosette in the centre – a symbol for Asterion. Perhaps, this was ancient Crete’s way of acknowledging its mythic son.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.