Polyphemus is best known as the Cyclops that Odysseus and his men encountered on their return from the Trojan War. But, is there another side to this man-eating giant? And what happened to him after Odysseus sailed away?

The legend is born

Polyphemus was one of the many children born to Poseidon, and to Thoosa the daughter of the primordial sea-god Phorcys. Polyphemus and his brothers are not to be confused with the three Cyclopes that were born to Uranus and Gaia, along with their 12 Titan siblings.

No, Polyphemus is the grumpy and reclusive Cyclops who lived in a mountain cave on the Cyclopean isles, near Sicily in Italy. This island is the home of these Cyclopean sons of Poseidon. It is not known if he and his brothers were brought into the world through any divine birthing ritual. However, it is conceivable that as both his parents were of the sea, that Polyphemus and his brothers came ashore after their primordial delivery.

It’s there, on the Cyclopean isles, where Polyphemus carried out his daily routine of herding sheep, making cheese, and keeping his own company. It is also here that he quickly gained a reputation for dining on lamb and mutton, sheep’s milk and cheese, and for developing a taste for human flesh. It is this latter preference that eventually leads him into trouble.

Odysseus arrives

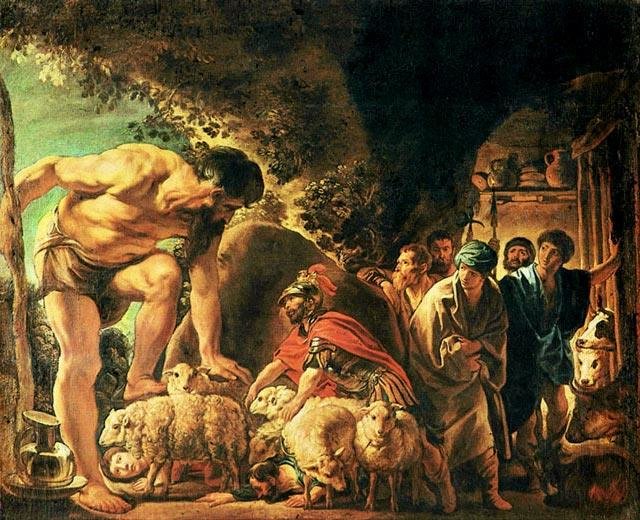

Whilst sailing back from the Trojan War, Odysseus and his crew land on the shores of the Cyclopean isles. In a search for provisions, they uncover Polyphemus’ store and help themselves. No doubt tempted by the aroma of human flesh, and angered by their rudeness, Polyphemus traps the men inside his cave by closing the giant stone door.

He denied these guests the customary hospitality; instead, devouring two of the men before going to sleep. When morning came, Polyphemus again attacked the crew, killing and eating another two men before leaving to graze his sheep for the day.

Odysseus and his remaining men were left all day inside Polyphemus’ cave. There they conceived of an escape and made preparations, including hardening a giant stake. When Polyphemus returned, Odysseus engaged him in conversation and offered him undiluted wine. The Cyclops once again proved himself rude and uncivilized by eating another two men.

Polyphemus then sealed his fate by offering Odysseus a guest-gift, or Xenia; the offer of friendship and hospitality, in exchange for Odysseus’ name. Wise to the cruel behavior of the Cyclops, Odysseus gives him the name “Οὖτις,” or ‘Nobody.’

“But when the wine had stolen about the wits of the Cyclops, then I spoke to him with gentle words: ‘So, you ask me the name I’m known by, Cyclops? I will tell you. But you must give me a guest-gift as you’ve promised. Nobody is my name, Nobody do they call me—my mother and my father, and all my comrades as well.’ So I spoke, and he straightway answered me with pitiless heart: ‘Nobody? I’ll eat Nobody last of all his friends—I’ll eat the others first! That’s my gift to you!’” ~ The Odyssey, Book IX

As Polyphemus’ drunken state takes hold, he falls asleep, and this is when Odysseus and his men strike. They maneuver the wooden stake above the Cyclops’ eye, plunging it into the soft-muscle, blinding Polyphemus. The Cyclops began shouting for help from his brothers, but on hearing that ‘Nobody’ has hurt him, his brothers believe it to be a divine situation and suggest prayer as the solution.

In the morning, Polyphemus opens the doorway to let his sheep out for grazing. But, aware that his attackers, and breakfast, are still inside he counts the sheep as they exit by feeling their backs.

Unbeknownst to the blind Cyclops, Odysseus and his crew have tied themselves to the underbellies of the sheep. Thus, they escaped as the sheep exited the cave, but not before Odysseus tells Polyphemus his real name; an act of hubris that will have ramifications later.

Upon realizing that the men have fooled him, Polyphemus charges down to the shore, shouting and hurling rocks at the men. Polyphemus prays to his father, who appears not to respond to his blinded son. Hearing no answer, he continued to throw rocks at them, only narrowly missing the departing ship.

We hear again of Polyphemus’ rage when Aeneas describes having watched the Cyclops using a “lopped pine tree” as a walking staff. With this aid, the giant staggers down to the shore where he washes his oozing eye socket, the painful groans echoing out across the water.

It is here that Aeneas encounters Achaemenides, one of Odysseus’s crew, who was unfortunately left on the island as they fled. The lost crew member tells Aeneas how his crew escaped and he is taken aboard, with Aeneas’ ship casting off immediately as Polyphemus discovers them. The Cyclops’ roars of anger and frustration draw the other Cyclopes to the shore, only to see the ship on the horizon.

Love-sick Polyphemus?

Whilst most of us are well acquainted with the story of Odysseus and Polyphemus, there is a second account of the Cyclops that appears sometime later, although apparently pre-dates the interaction with Odysseus. Some Classical writers have made a link between the nymph Galatea and Polyphemus, with different portrayals of his behavior.

The best known of these accounts is a play by Philoxenus of Cythera, which dates from 400 BC. In it, there is a link between the author, and Dionysius I of Syracuse, and the king’s mistress, Galatea. In the play, the author is represented as the Odysseus character, and the king as the Cyclops, with the two lovers escaping.

Fragment of wall painting depicting the Cyclop Polyphemus and the Nymph Galatea sensuously kissing in the arms of each other. Also visible: ram, Pan flute, shepherd stick. Pompeii, House of the Ancient Hunt (VII, 4, 48).

Theocritus was more sympathetic with his pastoral poetry, wherein Idyll XI and Idyll VI, Polyphemus is transfigured into the role of a herdsman who finds solace in song over his love for Galatea. Bion of Smyrna is also much kinder in his portrayal of Polyphemus and the Cyclops’ undying love for the sea-nymph, Galatea.

However, it is in Lucian of Samosata that there are indicators that Polyphemus’ relationship with Galatea was more successful. Lucian suggests that Galatea has sisters, and that one known as Doris is jealous of their relationship, but that Galatea does not love Polyphemus—a fact that fails to bother him, as he has chosen her above all others. Whilst there are other versions of this same theme, it is perhaps Ovid’s depiction that we recognize as having similarities to Odysseus’ encounter with the Cyclops.

In his Metamorphoses, Ovid describes the blind rage that Polyphemus flies into upon spying Galatea and the mortal Acis during their lovemaking. In his enraged state, Polyphemus crushes Acis with a rock, with Galatea fleeing into the water. She returns only briefly to change Acis into the spirit of the Sicilian river .

“Acis, the lovely youth, whose loss I mourn,

From Faunus, and the nymph Symethis born,

Was both his parents’ pleasure; but, to me

Was all that love could make a lover be.

The Gods our minds in mutual bands did join:

I was his only joy, and he was mine.

Now sixteen summers the sweet youth had seen;

And doubtful down began to shade his chin:

When Polyphemus first disturb’d our joy;

And lov’d me fiercely, as I lov’d the boy.” ~ Ovid, Metamorphoses

Polyphemus today

It is perhaps this version of events that we are most familiar with, as it was popular during both the Renaissance and Baroque periods. During these times of increased artistic creativity, we see many paintings, sculptures, poems, and music created.

In 1627, Luis de Góngora y Argote produced Fábula de Polifemo y Galatea, as a homage to the work by the same title (1611) by Luis Carillo y Sotomayor. The story was also given an operatic overhaul and made popular by Antoni Lliteres Carrió (1708). Polyphème en furie, a sonnet by Tristan L’Hermite in 1641, was produced as a condensed version that contained only 14 lines. Italy also embraced the story, with Giovanni Bononcini’s Polifemo in 1703, and George Frideric Handel’s cantata Aci, Galatea e Polifemo that was written in that country.

In 1718, John Gay composed work that would later be given to and updated by Mozart and Mendelssohn. It also followed the Theocritan pastoral style, but largely focuses on the two lovers over the actions of Polyphemus. There are many more musical representations that span the years into the 21st century with Reginald Smith Brindle’s El Polifemo de Oro (1956) and Andres Valero Castells’ Polifemo i Galatea, written for brass band in 2001.

Polyphemus has been portrayed in many sculptures and paintings as well, including paintings by Giulio Romano in 1528, Nicholas Poussin in 1649, Corneille Van Clève in 1681, and others like François Perrier, Giovanni Lanfranco, Jean-Baptiste van Loo, and Gustave Moreau who painted a whole series. Auguste Rodin’s series of clay statues from 1888 that were later cast into bronze statues are well known and may have been inspired by the work of Auguste Ottin from 1866.

What does appear to be a theme in all of these works, is the moment of rage that comes over Polyphemus upon discovering Acis and Galatea, and the casting forth of a rock as the lovers flee; somewhat akin to the Cyclops’ reaction towards Odysseus.

Conclusion

Whilst it is hard to imagine Polyphemus, a man-eating and crude Cyclops, having fallen in love with a sea-nymph, it is plausible to believe the link from Ovid’s description of his rage-filled behavior.

Perhaps it is this link that fueled the Cyclops’ taste for man-flesh; with feelings of anger and unrequited love, it is understandable that Polyphemus would punish any man who took what the Cyclops felt was his.

However, it is this attitude that ultimately betrays him, distorting fact and duty from emotion and mentality. When Polyphemus set about to punish Odysseus and his men, he broke the rules of hospitality and further insulted his guests by lying in his offering of Xenia.

This is what brought about his physical blinding by the legendary hero, and also thrust the Cyclops into the pages of history as a cruel and vengeful giant who was bested by a scared and desperate man.

The blinded Polyphemus seeks vengeance on Odysseus: Guido Reni’s painting in the Capitoline Museums.

If we learn nothing else from the story of Polyphemus, it should be to be slow to anger, to be generous to strangers, and to not break the laws of hospitality. For if we do, we leave ourselves blind, with nobody to blame but ourselves.

One comment

Didn’t Odysseus also break the rules by stealing from Polyphemus? I don’t know how all of the rules go, but it seems that would also be poor form.

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.