by Ben Potter, Contributing Writer, Classical Wisdom

To literary-minded ‘Moderns’ (if we can be so contrasted with the ‘Ancients’) the broad contents of the Iliad and Odyssey are quite familiar. Indeed, tales of wrathful Achilles, fearsome Ajax, tragic Hector, Sirens, Cyclopes, Circe, Suitors etcetera are well-known even to those who have not read both epics – so deep are they in the literary collective consciousness that they even make up parts of popular speech (e.g. “Achilles’ heel”).

Therefore it is perhaps surprising, given that the ancients’ knowledge of the wider Trojan myth would have been a sine qua non, that it is not something that has pervaded mainstream modern literary knowledge… even if the highlights of the Homeric epics have.

Granted, we all know about the golden apple and, yes, you’re right, Helen’s abduction gets plenty of press, but what about the details? What happened between the elopement and the first spear being thrown? And how many of us are aware that the battle royale between Achilles and Hector was the dramatic climax of the second Trojan War? For most of us, there are big gaps in our appreciation of this magnificent myth.

So, without further ado, let’s try to put that right!

The First Trojan War

The most obvious place to start is with the last point mentioned, i.e. TWI.

The most obvious place to start is with the last point mentioned, i.e. TWI.

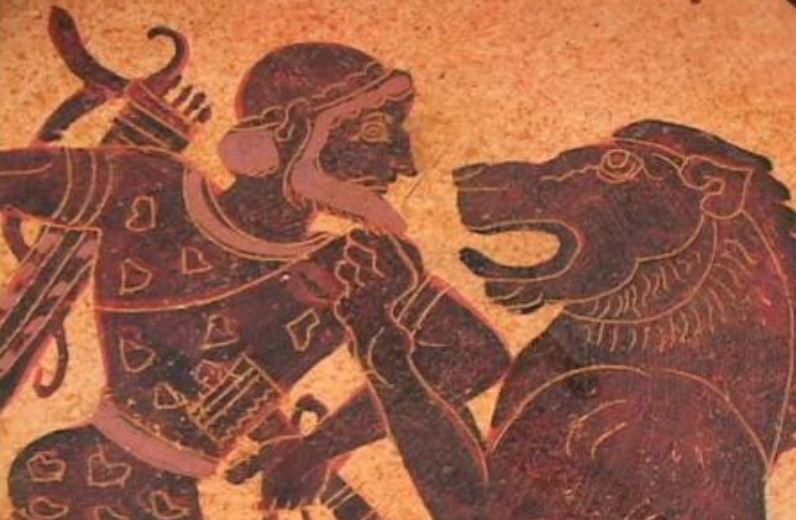

This was an expedition made two generations prior to that of the Homeric heroes Achilles, Odysseus, Agamemnon et al.. That the campaign is not more famous is really quite remarkable considering that it was led by none other than that uber-hero himself, Hercules!

Hercules’ casus belli for sacking the great citadel and putting every infant prince, save only the Homeric Trojan king, Hector’s father, Priam, to the sword was probably a far most justifiable and understandable reason than that given for the second war.

N.B. Priam was originally known as Podarkes, but, as he was spared because of a ransom paid for his life, he took the name Priam (from priatos, ‘ransomed’).

The King of Troy during TWI, Laomedon, had been given two horses by King of the Gods, Zeus, which were so swift that they could run on water; a reparation for Zeus abducting the beautiful Trojan boy, Ganymede. These horses were promised to Hercules by Laomedon should the former slaughter a terrible sea-monster that was threatening the latter’s fortress.

With flexed muscles and the hair on his buttocks standing up “like the quills on the fretful porpentine” (apparently he had an unusually shaggy posterior – otherwise I’d never have tried to show off with that quote from Shakespeare [Hamlet; act 1, scene 5 if you’re interested]), Hercules fulfilled his end of the bargain. Laomedon did not.

N.B. This was well in keeping with Laomedon’s form – the sea-monster had only been sent in the first place because he’d refused to pay Poseidon for building the walls of Troy.

Of course, such a rich saga conjures up images of a great and ancient city fortified for centuries against the machinations of fate. Not so! In fact, Laomedon was only a third generation Trojan. His grandfather, Tros, gave the land its name while Tros’ son, Ilus, was the man who founded the citadel, in turn giving it his name, i.e. Ilion, after which the world’s first literary masterpiece is named.

Anyway, enough of our early days of Troy lecture… what of the origins of the second (i.e. famous) war?

Root Causes

Well, there’s the aforementioned tale of the apple: Eris, the goddess of discord, is barred from attending the wedding of Achilles’ parents so she lobs a golden apple with ‘to the fairest’ inscribed on it through the doorway. Predictably, Hera, Aphrodite and Athena bicker over who should have it. Zeus, bored and irritated, sends them off to be judged by the Trojan prince, Paris. After some naked strutting and, more importantly, bribing, Paris awards the apple to Aphrodite in exchange for the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, Menelaus’ wife, Helen.

Well, there’s the aforementioned tale of the apple: Eris, the goddess of discord, is barred from attending the wedding of Achilles’ parents so she lobs a golden apple with ‘to the fairest’ inscribed on it through the doorway. Predictably, Hera, Aphrodite and Athena bicker over who should have it. Zeus, bored and irritated, sends them off to be judged by the Trojan prince, Paris. After some naked strutting and, more importantly, bribing, Paris awards the apple to Aphrodite in exchange for the love of the most beautiful woman in the world, Menelaus’ wife, Helen.

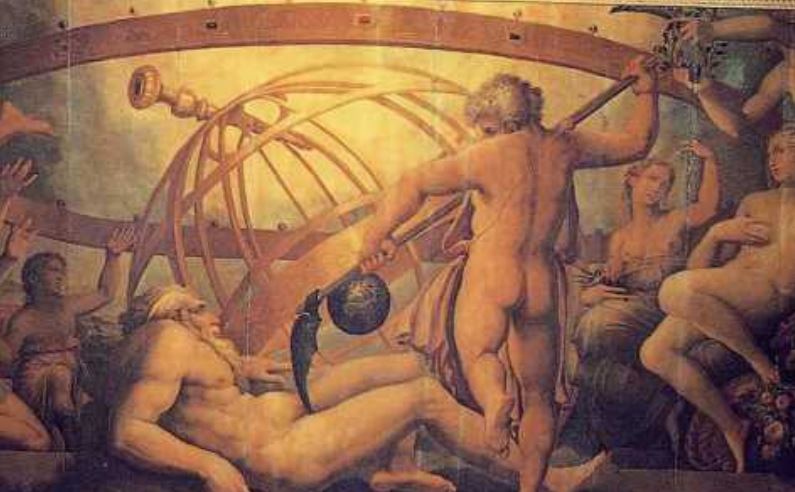

However, this is not the root cause, for that we must go into the dark and troubled corners of the wrathful mind of Zeus. Zeus only acceded to his lofty position as King of the Gods by overthrowing his father, Cronus. Cronus had come to the throne by… you guessed it, overthrowing his own father, Uranus. Consequently, Zeus was a little paranoid the same fate might befall him.

So, what better way to rid the world of a whole series of his demi-divine loin-fruit whilst at the same time giving the world a much-needed population cleanse than to engineer the Trojan War?

Whichever of these two motives was true, we can understand why Zeus is the only Olympian to take no side in the Trojan War – as long as men lie on the battlefield with dogs and carrion birds feasting upon their rent flesh, Zeus is happy.

The Greek Coalition

So, a recently sacked city has a war started against it via a combination of the caprice of one god, the mischief of another and the libido of a prince, but why did all the Greeks agree to fight? Helen was Queen of Sparta and Greece was far from a unified state – indeed Greek cooperation against a foreign foe was to remain the exception, rather than the rule, for centuries to come (this blurring of history and literature is not something the Greeks would have apologised for).

So, a recently sacked city has a war started against it via a combination of the caprice of one god, the mischief of another and the libido of a prince, but why did all the Greeks agree to fight? Helen was Queen of Sparta and Greece was far from a unified state – indeed Greek cooperation against a foreign foe was to remain the exception, rather than the rule, for centuries to come (this blurring of history and literature is not something the Greeks would have apologised for).

Well, this goes back to Menelaus’ betrothal to Helen.

Helen’s earthly father, Tyndareus (Zeus may have actually sired her), made the countless suitors vying for Helen’s hand swear that they would defend the marriage of whomever his daughter wed – thus when Helen was abducted, and after a failed effort from Menelaus and Odysseus to resolve the dispute diplomatically, the cuckolded king petitioned his brother, the most powerful of all the Greek kings, Agamemnon, to call in the debt promised by oath.

Thus a bevy of Greek kings and princes made their way to Troy – though not universally willingly.

True, many saw it as an ideal chance to gain riches and glory (some, like Achilles, only fifteen years old at the time, had not even sworn the oath to honour Helen’s marriage), but Odysseus, that great trickster, decided to feign madness rather than fulfil his sacred vow.

Thus, when Palamedes arrived on Ithaca to sign Odysseus up, the wily Master of Stratagems began ranting, raving and sowing his fields with salt. However, Palamedes was not to be fooled so easily, he placed Odysseus’ infant son, Telemachus, in front of the plough (or, in other accounts, simply threatened to run him through) and Odysseus, reluctantly, was forced to break character and take the King’s shilling.

This moment, which would come to cost Odysseus twenty years of his life, was never forgotten by Homer’s second son. He ended up framing Palamedes for treason, a move that saw his recruiter unjustly stoned to death.

So, finally, the Greeks could set sail for Troy, but, with the slight disadvantage of not knowing where it was, actually landed in Mysia where they engaged in battle with Hercules’ son, Telephus before being scattered to various shores by the winds. Telephus had been incurably wounded by the Greeks and so sailed the seas in order to seek them out and be healed (this did, for some reason, seem to make sense!). When he was finally restored to his former glory he told the Argives the way to Troy as a thank you.

Although some disclaim this venture from the narrative, others assert that it was very much a key part of the story… and a part that set the expedition back by up to eight years!

More Set-backs

Regardless, when the thousand-plus strong flotilla finally convened (or reconvened) at Aulis, they were ready and willing to finally bring the fight to Troy, to win glory or die trying. Unfortunately, they were not actually able to do so.

Regardless, when the thousand-plus strong flotilla finally convened (or reconvened) at Aulis, they were ready and willing to finally bring the fight to Troy, to win glory or die trying. Unfortunately, they were not actually able to do so.

The goddess Artemis, peeved with the hubris of Agamemnon, had stopped the winds from blowing Troy-wards and would only reactivate them if he sacrificed his daughter, Iphigenia. This, he eventually did – a move that would prove to be his undoing when he returned home after ten years to his—understandably—rather cross wife.

Like with the stories of the trials, tribulations and trysts of the members of the Greek pantheon, there are various different accounts of these stories, all with their own embellishments and contradictions. This, however, did not seem to be an issue for the Greeks. Indeed, the Athenian playwrights used a great deal of artistic licence in tweaking various details of the myths in order to create new and thought-provoking plotlines.

It should be stressed that what is given above is merely a brief précis of the back-story to the works of Homer. Though these tales may be seen today as a useful adjunct to the main event, for the Greeks they were essential and assumed histories – parts of the plot that every educated, and perhaps even uneducated, person was required to be familiar with.

To be unaware of the origins of the Greek coalition would be to be unaware of the Thirteen Colonies, of the Boston Tea Party, of Washington’s cherry tree and wooden teeth, of Hancock’s liberal use of paper, of Franklin’s suicidal kite-flying and… ahem… ‘loving’ nature.

History vs. Literature

Indeed, the comparison is a poignant one as the Greeks didn’t see the Trojan War and the works of Homer as mere literature, but actual history. True, some certainly took the more fanciful and divine parts to be allegorical or a result of artistic licence, but few seriously doubted that such a war, with such characters, really took place and really defined the fate of their nation.

Thus, to truly understand and appreciate Homer beyond his talent as a poet and story-teller, it is helpful to have a curiosity about the wider, Greek, mythological world.

Not that such a renowned source needs much of a plug from us, but Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths is an entertaining and accessible prism through which to view the beauty and splendour of the Ancient oeuvre for those whose appetite has been whetted, but not sated.

Though now, dear reader, we leave you with, hopefully, a greater interest, understanding, curiosity or appreciation of the world surrounding the Homeric tradition. For as traditions go, it is one worth appreciating and absorbing. After all, there aren’t too many that have lasted for nearly 3000 years… and even fewer that only get more fascinating with each year that passes, and each reading that is completed.

No comments yet. You should be kind and add one!

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.