And so it comes to be, that all men must die. Yes, even the old ones. The great poet and dramatist, Sophocles, was approaching his own end when he imagined the glorious finale of the tragic figure, Oedipus in Oedipus at Colonus.

This play is thought to be Sophocles’ final one because it was first produced in 401 B.C., four years after his death. And just to add to the confusion, the events that occur in the story are actually second chronologically in the Oedipal myth series. Wedged between the action packed stories of Oedipus Rex and Antigone, this tragedy is more philosophical than the others, paying attention to shifting characters and morality. It addresses fate full on and creates a triangle of power between the good, the bad and the blind beggar.

In a nutshell, it is the tale of two ancient cities, three kings and the slow, painful process of redemption.

Oedipus Rex, the first episode, finished with its eponymous character banished and blinded. The previously glorious king, who unknowingly committed incest and patricide, boldly bewailed his fate, accepted responsibility and sadly left his kingdom. This contrasts sharply with the enfeebled and humbled Oedipus in the second section of the tragic tale.

But let’s review quickly.

He, the one and only Oedipus, arrives in the village of Colonus, which is just outside Athens and also – very interestingly- Sophocles’ birthplace. He is unrecognizable from the monarch he used to be. The ultimate tragic hero is no longer bold, nor decisive, nor very regal. His previous ownership of his actions and destiny has vanished into thin air. He rejects the guilt of his deeds. Acts committed unknowingly make the man innocent, surely? He is clearly weakened by his many, lonely years wandering.

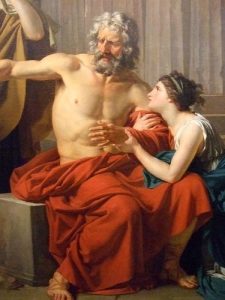

He, the one and only Oedipus, arrives in the village of Colonus, which is just outside Athens and also – very interestingly- Sophocles’ birthplace. He is unrecognizable from the monarch he used to be. The ultimate tragic hero is no longer bold, nor decisive, nor very regal. His previous ownership of his actions and destiny has vanished into thin air. He rejects the guilt of his deeds. Acts committed unknowingly make the man innocent, surely? He is clearly weakened by his many, lonely years wandering.The first scene of Oedipus at Colonus begins with Antigone, his daughter, helping him walk into a grove, but not just any vegetable patch. This garden happens to be scared, which quickly draws the Chorus to admonish the old man. They are unrelenting until the tragic figure’s identity is revealed. When Oedipus finally figures out where he is, he discloses to Antigone that the oracle predicted this location as the spot of his death. Furthermore, there would be a blessing to the city that buries him.

Upon Oedipus’ request, the king of Athens, Theseus, is summoned to decide whether this unseeing hobo should be expelled once more. Before the monarch arrives, however, Oedipus’ daughter, Ismene, enters and recounts the unfortunate happenings in Thebes. The two brothers, Oedipus’ sons, are fighting for rulership in the wake of their father’s infamous downfall.

Apparently, the youngest scoundrel is in cahoots with Creon, Oedipus’ brother-in-law/uncle and the eldest is exiled. The first son’s pride is bruised and therefore he amasses an army to take back Thebes.

Theseus enters. Knowing Oedipus’ story, he is empathetic to the unfortunate man. The king grants him protection, even when he understands it will mean war and an uncomfortable confrontation with Thebes. He offers the gift of a proper burial and all praise the glory of Athens.

Creon enters. Full of treachery, deceit and the usual villainy, he attempts to bring Oedipus back to Thebes. He also knows the oracle and wants the prophesied protection his favorite corpse-to-be will bring. He kidnaps Antigone and Ismene and threatens to force Oedipus back. The bully almost has his way until the benevolent Theseus acts and returns the daughters to their father.

But the family feud does not end there. The banished brother appeals to his father for help, but his requests fall on deaf ears and blind eyes. The son was not there for Oedipus when he was exiled, and the father cannot forgive his progeny’s grave disrespect. Oedipus sends him away with a curse that the two boys will kill each other.

Finally, sweet, peaceful death comes. Thunder resounds, signaling that it is time for Oedipus’ final rest. Preparing the rituals, he meets his end in a sacred and secret spot. So special that Theseus only knows it, so the noble king can enjoy the God’s blessings.

And so we have Oedipus’ redemption. After being reviled, shamed and stained, Oedipus is finally sought after. His unimaginable deeds have been forgiven after his years of punishment, and sanctified with a divine gift. Once exiled, now Oedipus has kings beseeching him to come to their city. The blind man who was pleading for protection, eventually, and ironically, leads the king of Athens.

In short, Oedipus began as a noble and strong ruler and became a debased and decrepit vagrant. Finally, as fate would have it, he was restored as a messenger of the gods with divine gift to give.

Oedipus’ full cycle of highs and lows is clearly contrasted with the other two kings, Theseus and Creon, who are positioned as polar opposites, extreme regal examples. The Athenian monarch, Theseus, represents the good, the empathetic and the noble. He, like the city he reigns, is praised by the Chorus and by Oedipus as being fair and just.

In contrast, Creon is a vile, lying, threatening royal who the audience and Oedipus hate and fear. His city Thebes, the long-standing rival of Athens, was considered a place where proper boundaries and identities were not maintained. A place where incest and murder could happen.

However, this depiction of good ole Athena town was no longer true. As Sophocles’ life was drawing to an end, so was the golden age of Athens. The Peloponnesian War, which brought the fair state to its knees, reached its end only a year after the playwright’s death. The surrender in 404 B.C. stripped Athens of its walls, its fleet, and all of its overseas possessions.

Oedipus at Colonus, therefore, was like a swansong. A final ode or maybe glorious nostalgia by a very old man of what once was. Praise for a city coming to its demise. But then again, everyone likes a happy ending. Athens had it, if only fictionally, so why shouldn’t Oedipus? His death is the perfect conclusion. After being seen as so repulsive, he is finally accepted.

But this play was more than that. It was also the philosophical statement and justification that actions unintended are not our fault – the antithesis of Sophocles’ earlier editions and a very clear change of heart.

And so, perhaps, character and writer became one. Oedipus and Sophocles sing praises of the good, come to terms with one’s deeds in life and then, finally, prepare for death.

Oedipus at Colonus was written by Sophocles around 406 b.c. Produced in Athens, Greece. You can read the full story here: https://classicalwisdom.com/greek_books/oedipus-at-colonus/

Make sure to read the next installment of the Oedipal myth for next week’s essay. This time it’s a play written by Aeschylus called The Seven Against Thebes. You can view the whole text here for free: https://classicalwisdom.com/greek_books/the-seven-against-thebes/

9 comments

Now, I don’t want to sound like just another sectklir with a Classics degree, but that is a gross simplification of Greek literature. 5th century tragedy certainly has a few themes, I’m not arguing with you there, but Sophocles and his contemporaries are complicated work, which is why it’s been the subject of scholarship for over two thousand years. Some of the themes are so inaccessible that we don’t even have English words to describe them. When you boil down Oedipus and Antigone, which have very different messages, into Great men are held so highly that they become so arrogant and make horrible mistakes you can transfer that story onto just about anything without working to hard. So Obama was on your mind, but now think about Nixon and Watergate, or Clinton and Lewinsky. Now think about Britney Spears or Tiger Woods it still works doesn’t it? If you’re going to read Greek literature, you should do so with an open mind, don’t just use it as an allegory to confirm opinions you already hold.

Hi Abe! Stumbled upon your post.. Thanks for giving birth to this miauengfnl idea for us to work on. Had a fruitful experience and i have learnt alot. Hope that you’re doing great at the moment and keep in touch =)

Only a smiling visitant right here to talk about the adore , btw fantastic pattern. Better absolutely you should forget along with smile than that you just ought to remember and be sad. by Christina Georgina Rossetti.

http://www.beatsbydre-spiderman.com

I simply want to say I’m all new to blogging and site-building and certainly savored this web-site. Probably I’m likely to bookmark your blog post . You really have terrific articles. Bless you for sharing your web page.

… – I searched and found it. Thanks for the post. Ann Santo

;> I do not agree with you. Why? v_v bye

Nice post. I add this blog to rss feed. Bye

Hi man! I need a phone number to the administrator. PM me [email protected]

Great :D :D Now I know the real story.. Thanks

Trackbacks

Our apologies, you must be logged in to post a comment.